On the evening of December 7, 2022, people in a large fraction of the U.S. will be able to see a rare and wonderful astronomical event: the moon will pass directly in front of Mars, blocking it from view.

This event, called an occultation—from a Latin word meaning “hidden”—happens once or twice per year somewhere on Earth. But like a solar eclipse, you have to be in the right place at the right time to see it. Think of the upcoming one as a Martian eclipse.

You don’t need any special equipment to watch: just your eyeballs (and probably something warm to wear). Like a well-plotted movie, the drama will build as the moon slowly approaches Mars in the sky, culminating in the moment when the edge of our satellite sweeps over the disk of the planet, causing it to fade away and finally wink out. A telescope improves the view of course, but it’s still fun to watch without optical aid.

I’ve seen quite a few occultations of stars by the moon and even one in which our natural satellite passed right in front of Venus, which was honestly very cool to witness. I’ve never seen the moon occult Mars, though, so I’m looking forward to this.

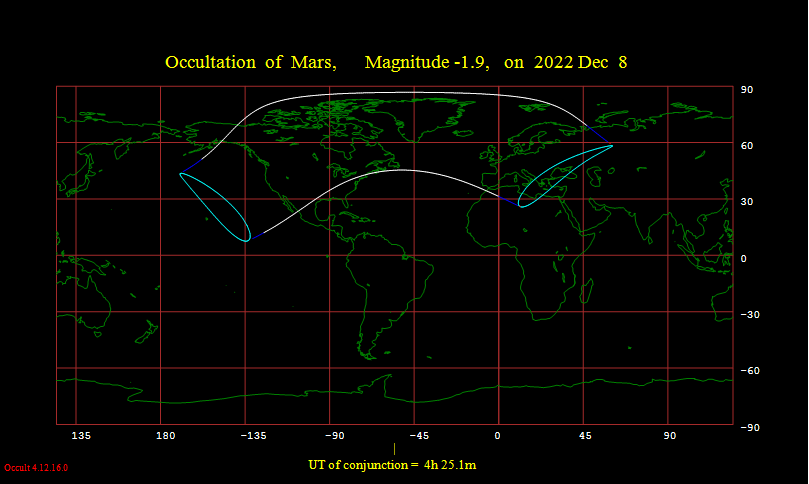

The folks at the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) have a map on their site that shows where the event will be visible.

Everyone inside the curved white path can see the occultation. If you’re inside the teal ovals, then it happens when the moon rises or sets, so visibility will be limited. This shows that almost all of the U.S. except for the southeastern region, as well as all of Canada and much of Europe, will see the event. (Note that the IOTA map uses Universal Time (UT). So in UT, the occultation occurs in the morning of December 8, but in local time in the U.S., it happens in the evening of the night before that date.)

The exact timing of the event for you depends on where you’re located. The moon is much closer to Earth than Mars, which affects how we see it. When you hold your thumb out at arm’s length and look at it with just your right eye, with your left eye closed, and then look with your left eye, with the right one closed, your thumb appears to jump back and forth, compared with more distant objects, because you’re seeing it from slightly different angles with each eye. This is called parallax, and it also works on astronomical scales, changing the moon’s relative position in the sky depending on your latitude and longitude.

The IOTA page has a list of timings of the event for many cities. Look for one near you to get an idea of when it happens. But again, bear in mind your exact location changes the exact timing. Your best bet is to use some planetarium software to be as precise as possible. Stellarium is a free site, for example, and you can search online to get a list of quite a few apps for mobile devices. Once they have your location, they can give you pretty decent numbers for when the occultation occurs for you.

So how does this all work, physically?

The planets, including Earth, all orbit the sun more or less in the same plane. Because we’re in that plane, we see it edge on as a line across the sky called the ecliptic. The planets all stick pretty close to the ecliptic. The moon, however, has an orbit that’s tilted relative to it at an angle of about five degrees. As the moon orbits Earth every 29 days, it makes a big circle around the sky, crossing the ecliptic twice. (Imagine two hula hoops, one inside the other, and both tipped a bit. They cross in two places called nodes.) The moon passes any given planet in the sky once every month, but because of the former’s tipped orbit, the two usually miss each other by several degrees.

Sometimes, however, a planet will happen to be at the exact spot in the sky where the moon’s orbit crosses the ecliptic. And if the moon happens to be there at the same time, an occultation will occur.

This is RIGHT NOW. @NASA_Orion is looking back at Earth and the Moon from distant retrograde orbit. Watch the #Artemis I livestream: https://t.co/Qx1QFUdD08 pic.twitter.com/zMTorYQvjS

— NASA (@NASA) November 28, 2022

On November 28, 2022, on its journey into a distant retrograde lunar orbit, the Orion spacecraft on NASA’s Artemis I mission captured this image of our planet “setting” behind the moon: a lunar occultation of Earth! Credit: NASA

In this case, what you’ll see after sunset is the moon and Mars very close together in the sky. As the moon orbits Earth, it moves by about half a degree—its own diameter, or roughly half the width of your thumb at arm’s length—in an hour. So just before the actual occultation, the two are quite close together. As the event progresses, the moon and Mars creep closer together, until finally the moon’s edge starts to slide across the planet’s disk.

It takes about 30 to 45 seconds for the moon to cover Mars entirely, like slowly drawing a curtain across a window. By eye, the two will seem to kiss, and then Mars will fade from view in less than a minute.

The moon’s motion will continue with Mars hidden behind its bulk, and depending on your location, it could take as much as an hour for the Red Planet to reappear on the other side of the moon.

The specific circumstances for this event are remarkable. For one thing, the moon will be full, a silvery disk in the dark sky. For another, the occultation happens when Mars is at opposition. Once every two years or so, Earth catches up to and laps Mars around the sun, like a race car on an inside track passing a slower car on the outside. When this happens, Earth is directly between Mars and the sun, which means that, to us, they are on opposite sides of the sky (hence the event name). This arrangement also means Mars is as close to Earth as it will get for two years. In turn, this means the Red Planet looks its biggest and is at its brightest as well.

If you’re an avid sky watcher, you may have noticed Mars in the evening sky, a brilliant “star” shining in the east after sunset, more brilliant than usual because of its proximity to us. It has a noticeable orange hue—most of the surface is covered in oxidized iron-rich dust, so it’s literally rusty. No wonder the ancient Greeks and Romans equated the planet with their god of war. It’s a bloodshot baleful eye glowering down at us from the heavens! And that eye will wink at us.

Occultations have scientific use. The characteristics of a distant asteroid can be deduced when it passes in front of a star. Observers at different latitudes see the star pass behind a different chord through the asteroid, so the observations can be combined to measure the latter’s size and shape.

Also, many exoplanets—alien worlds orbiting other stars—have been discovered using a similar method. If we happen to see an exoplanet’s orbit edge on, then once per revolution, it passes in front of its host star, creating a mini eclipse called a transit. The star dims a fraction, and from that the size of the planet can be found. In some cases, it’s also possible to determine the planet’s atmospheric composition. The majority of the more than 5,000 exoplanets that have been discovered were found using the transit method.

One thing to keep in mind as you watch the upcoming occultation: Right now NASA and other space agencies have their own eyes on the moon. The recently launched Artemis I mission sent the Orion space capsule into a wide, looping orbit around our natural satellite, and it is due to return to Earth in mid-December. This mission is uncrewed, but the next will have people onboard to orbit the moon. And the third is planned to set humans down on its surface, the first boot prints to be left in the lunar dust since 1972.

NASA already has long-term plans to send humans to Mars, too. Both worlds have quite a few space probes orbiting and sitting on them, and people may not be far behind. When you watch the moon cover Mars on the night of December 7, you will see a metaphor for our future in space.

The moon looms large, with the more distant Mars patiently waiting for us.