Tempo will also be able to track variations in pollution at the neighborhood scale. Lefer foresees this being especially useful for exposing environmental injustice, since lower-income and racially segregated areas are more likely to be near emissions sources, like ports and refineries. “And satellite data can show that,” he says. Weather forecasting will benefit, too: With information constantly collected across greater North America, agencies will be able to more accurately infer future conditions, particularly in places where data currently exists for only a certain time of day.

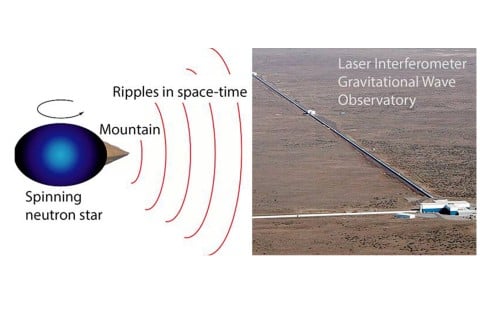

But this mission has its limits: Satellites only look down, just as remote-sensing ground monitors only look up. A lot gets missed that way, like details about which pollutants are at different altitudes, says chemist Gregory Frost of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That’s why this summer NASA will partner with NOAA, the National Science Foundation, and several other institutions to fill in the gaps between space and the ground. Instruments aboard NASA’s DC-8, Gulfstream III and V, and other jets will characterize trace gases and aerosols above urban areas like New York City, Los Angeles, and DC, as well as coastal regions.

These readings will calibrate Tempo’s space data and add to it in areas that lack good satellite or ground coverage. Combine all of this data with information from EPA monitors and weather models, and scientists will soon be able to analyze the atmosphere from multiple points of view. “Once we do that,” Frost says, “it’s going to be like having an air pollution monitor everywhere.”

Scientists are particularly interested in chasing pollutants called PM 2.5, or particles with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers. Aerosols like these make up less than 1 percent of the atmosphere. That’s not a lot, Frost says, but all air quality problems have to do with these trace components. They harm crops, worsen visibility, and are small enough to lodge themselves into people’s lungs, which can lead to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Tinier particles—less than one micrometer across—can even get into the bloodstream.

“Airborne particulate matter is considered to be the top environmental health risk worldwide,” says David Diner, a planetary scientist at NASA. But which types of PM 2.5 are most harmful to humans is still mostly a mystery. “There’s always this question about whether our bodies are more sensitive to the size of these particles or their chemical composition,” he says.

To find out, Diner is heading up NASA’s first collaboration with major health organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. In partnership with the Italian Space Agency, the groups are aiming to launch an observatory next year called MAIA, or Multi-Angle Imager for Aerosols, which will sample the air over 11 of the planet’s most populous metropolitan areas, including Boston, Johannesburg, and Tel Aviv. The imager will measure sunlight scattering off of aerosols to learn about their sizes and chemical makeup. That data will be passed off to epidemiologists, who will combine it with information from ground-based monitors and compare it against public health records to figure out what sizes and mixtures of particles correlate with specific health problems, like emphysema, pregnancy complications, and premature death.