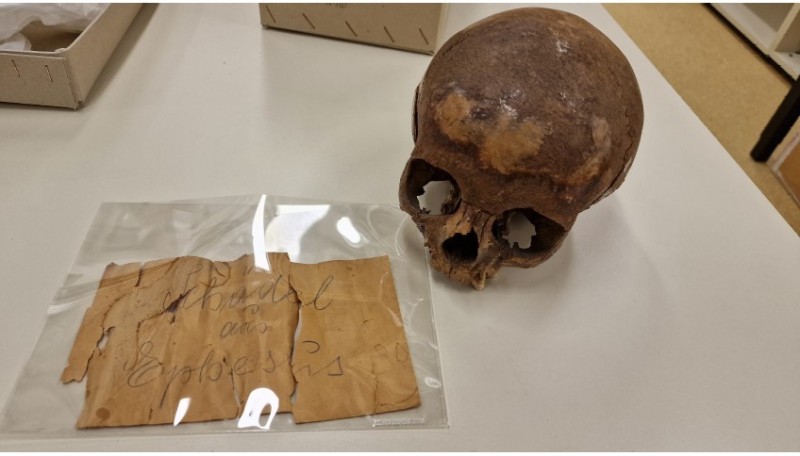

A skull long thought to belong to Cleopatra’s murdered sister has been revealed to be that of a young boy with developmental disorders, according to new research published in Scientific Reports. The discovery, made using modern forensic techniques, puts to rest decades of speculation about the final resting place of Arsinoë IV while raising intriguing new questions about the boy’s identity.

The skull, discovered in 1929 in the ruins of a magnificent building called the Octagon in Ephesos (modern-day Turkey), was initially believed to be from “a very distinguished person” and a young woman. The location and timing seemed to match historical records of Arsinoë IV, who was murdered there around 41 BCE at the instigation of Mark Antony, Cleopatra’s lover.

Modern Science Meets Ancient Mystery

An international research team led by anthropologist Gerhard Weber from the University of Vienna used state-of-the-art methods, including genetic analysis and micro-CT scanning, to examine the remains. Their findings reveal the skull belonged to a boy between 11 and 14 years old who suffered from significant developmental disorders.

The boy had an unusually asymmetrical skull shape and faced serious challenges with basic functions like chewing. His genetic profile points to origins in Italy or Sardinia, suggesting he may have been part of the Roman community in ancient Ephesos.

A Magnificent Tomb

The mystery of why this young boy was buried in such a prominent location remains. The Octagon was a splendid building on the main street of Ephesos, suggesting the tomb was intended for someone of very high social status. Dating of the remains places them between 36 and 205 BCE, which aligns with the general historical period but opens new questions about the building’s purpose.

While this discovery means the search for Arsinoë IV’s remains must continue elsewhere, it has revealed an intriguing new historical figure. The research team’s findings highlight how modern scientific methods can both solve and create historical mysteries.

The research was published in Scientific Reports.

If you found this piece useful, please consider supporting our work with a small, one-time or monthly donation. Your contribution enables us to continue bringing you accurate, thought-provoking science and medical news that you can trust. Independent reporting takes time, effort, and resources, and your support makes it possible for us to keep exploring the stories that matter to you. Together, we can ensure that important discoveries and developments reach the people who need them most.