Acting outside the body, pheromones are chemicals that animals produce and release to elicit social responses from other members of their species. According to Ruvinsky, pheromones also inform animals about how to budget their finite energy.

When conditions are not conducive to reproduction, female animals will spend resources and energy maintaining their overall body health, including muscles, neurons, intestines and other nonreproductive organs. Sensing male pheromones triggers downstream signaling from the nervous system to the rest of the body, causing the female animals to shift their energy and resources to increasing reproductive health instead. The result? Better eggs but faster decay of the body.

“The pheromone tricks the female into sending help to her eggs and shortchanging the rest of her body,” Ruvinsky said. “It’s not all or nothing, but it’s shifting the balance.”

Salvaging recycled eggs

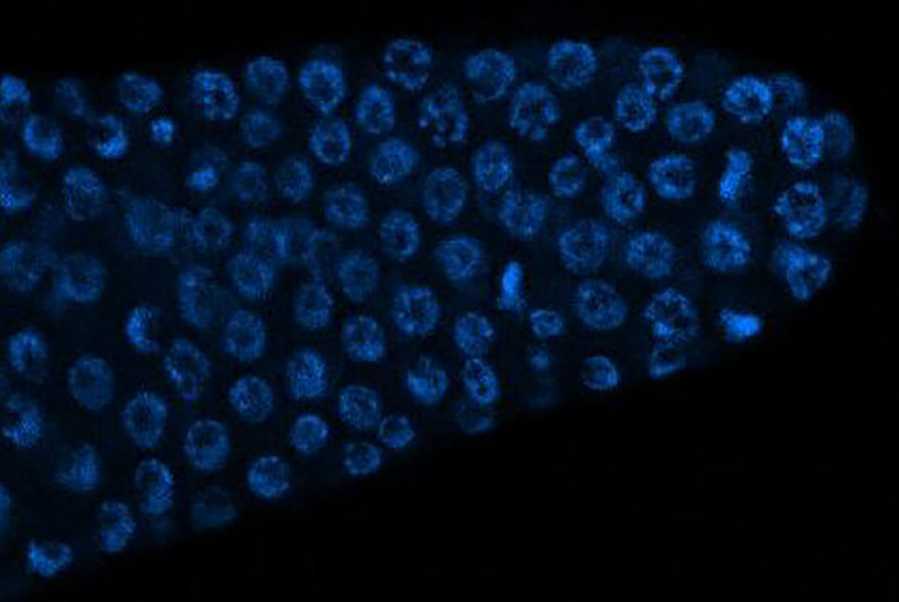

When female roundworms spent more energy on reproduction, they produced more egg cell precursors from stem cells. And, in a seemingly counterproductive move, most of these cells actually died. But Ruvinsky says this is not a mistake but a cleverly designed advantage.

“The majority of egg precursors die, and the spare parts are recycled to build better eggs,” he said. “We think that is essentially what’s happening. Production is increased. Most egg precursors die, and their parts are salvaged and recycled into a few, higher-quality eggs.”

Of course, there are unfortunate trade-offs. When female roundworms neglected the rest of their body to focus their energy on reproductive health, they were more likely to experience early death. Ruvinsky said this information, too, can advise future drug development for humans.

“The pheromones that roundworms use are not found in humans,” he said. “But the neurons they activate are very similar. We are working to design pharmacological interventions that manipulate these neurons to improve fertility while reducing the negative side effects. It remains to be seen, but it’s definitely worth trying.”

The study, “A male pheromone that improves the quality of the oogenic germline,” was supported by the National Institutes of Health (award number R01GM126125).