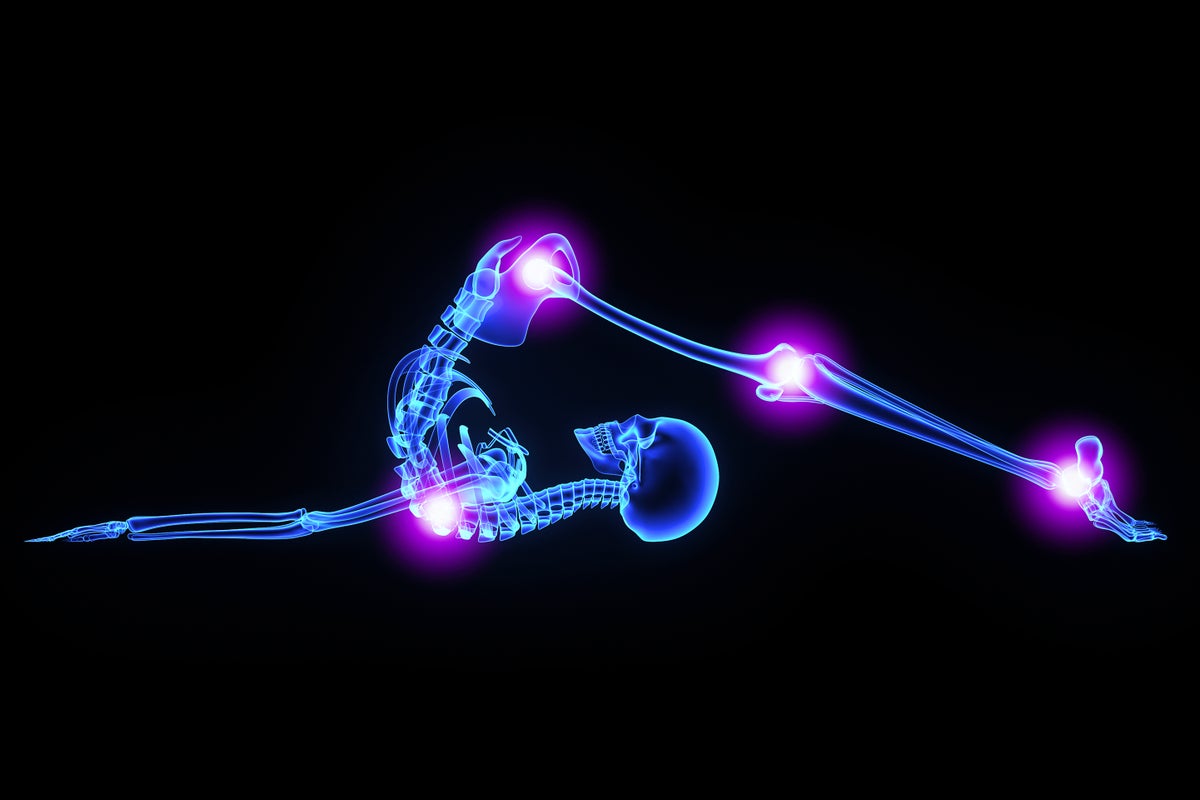

Middle age is when you get to know your joints. I have spent the last few years learning that my many youthful party tricks—popping shoulders out of their sockets on a whim, bending elbows backward—had painful long-term consequences. Twenty years of high-impact sports on an imperfect skeleton have also taken their toll.

I’m now gritting my teeth through the tiny movements assigned by physical therapy, desperately trying to save these things that let me bend, twist and move around. It’s not just the big-name celebrities of the skeleton—the hips and knees and shoulders—that scream at us as we accumulate mileage, but tiny joints that suddenly grab our attention, if not the ibuprofen. The vertebrae and the squishable, intervertebral discs between them. The joints between the teeth and the jaw. Even the joint at the very front of the pelvis, one most people never think about unless they are giving birth or taking a hit in sports, reveals it’s been taking hard knocks from life. These points of movement get arthritic, stiff. Bones begin to grind against one another. Movements that used to only pull or create pressure now produce pain.

It’s easy to blame joints themselves. Weak. Old. Crumbling. We’ve been betrayed by joints so small we never even really registered they were there. But joints are signs of anatomical triumph. They bend so we don’t break.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These points where two parts of the skeleton meet are so essential for movement that evolution has come up with them at least twice. Arthropods—whether crabs or cockroaches—developed their own version: joints in their exoskeletons that allow these creatures to bend and scuttle. Our rendition—the internal skeleton—probably also started out on the outside of the body of ancient creatures, as bony scales. Our spinal cords, the things that make us chordates, got a segmented bony coat around 420 million years ago. What’s now modern vertebrae are nothing but a pile of 25 joints (or occasionally 26 or 24, if you happen to have one more or less vertebra). The bones are stacked on top of each other, separated by spongy cartilage called intervertebral discs. We had lubricated joints before we even crawled out of the sea. Heck, without them, the crawling wouldn’t have happened in the first place. Joints have been modified now to let insects and animals skitter, slither, climb, run. Even fly. Without firm bones and the joints between them, there’s no defying gravity.

Joints are more than one bone on another. In between the majority of our joints, we have connective tissue, cartilage and bursas—thin flat sacs of fluid. They cushion and lubricate, helping our bodies bend easily, quickly and without sounding like a rusty door hinge. Joints that don’t bend still need this cushion. The joints—and the sacs between each one—allow the skeleton to shift and withstand pressure, even if that particular joint isn’t helping anyone do a backbend.

Many joints go almost entirely unnoticed—until something is about to go wrong. It might seem, for example, that adult teeth should not be wiggling around in the jaw socket. But in fact these dental alveolar syndesmoses (technical speak for the tiny ligamentous joint between the tooth and jaw socket) move all the time. They have mechanoreceptors—ways to measure movement—which process the tiny vibrations that inform you of a food’s texture. A larger tooth movement, and the very jolt that sometimes comes with it, is the final warning system that you should shell that nut first, please. Your uncracked tooth will thank you later.

Our feet balance a large load into two impossibly small points, and they don’t just stand, they point, arch, bend and flex. That flexibility is due to the 26 different bones and all the joints in between that make up the ankle and foot. It’s an evolutionary work-around, adapting the flexible tree-clinging feet of our ancestors to the pavement pounding model we use today.

In contrast, the pelvic girdle seems like a fairly continuous ring of bone. But it’s the joining of three bones on each side, the ilium, ischium and pubis. In the back, the pelvic girdle joins to the sacrum at the base of the spine. In the front, though, there’s a joint, the pubic symphysis. This joint can move a tiny bit in adults. But what it really does is help to distribute weight and absorb the shock that comes with the weight of the upper body. This joint splits that mass evenly over your legs. In people who give birth, this joint softens and becomes extra flexible. It bends and curves and stretches—creating extra space for a baby to pass through the birth canal. Then, most of the time, it snaps back to normal.

Joints are essential to how we experience the world, and we take them for granted—until they start to fail. Arthritis, that painful chronic swelling that often comes with age, creeps into the joints between our bones. Bursae become inflamed and bulbous. Decades of grinding up food take a toll on the teeth. Years of running and walking take the spring out of our step, and alongside childbearing, grind down the joints in the pelvis and spine.

As we age, intravertebral discs become compressed with the weight of our years—and the weight of our weight. They may bulge out into the spaces between the vertebrae themselves, pressing on nerve roots—a herniated disc. The spine doesn’t just bear the weight of our youthful indiscretions, but of our evolutionary fate. When our ancestors stood upright, we asked a lot of our vertebrae. A rigid spine couldn’t defy physics and stand straight, and so it curved. We acquired a lumbar lordosis, a sway in our lower backs. Unfortunately, that curve bears the pressure of our upper bodies. When sitting down, our lumbar spines are taking loads between 100 to 175 kilograms (220–385 pounds). When standing, it’s 90 to 120 kilograms (198 to 264 pounds). Despite this, our intervertebral discs bear the mass cheerfully—even improving in response to exercise.

When we think of bodily strength we think of long bones or muscles, things that only crack or tear under the worst pressure. In contrast, joints seem weak—in part because they give way before bones do. But their flexibility is our defense. Every weird tooth movement is a sensation, a broken tooth avoided. Every shift of the hips is a time they didn’t crack. Each step or lifted weight places pressure on the joints in our bones, and the joints gently give way. Joints remind us that there’s strength in flexibility.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.