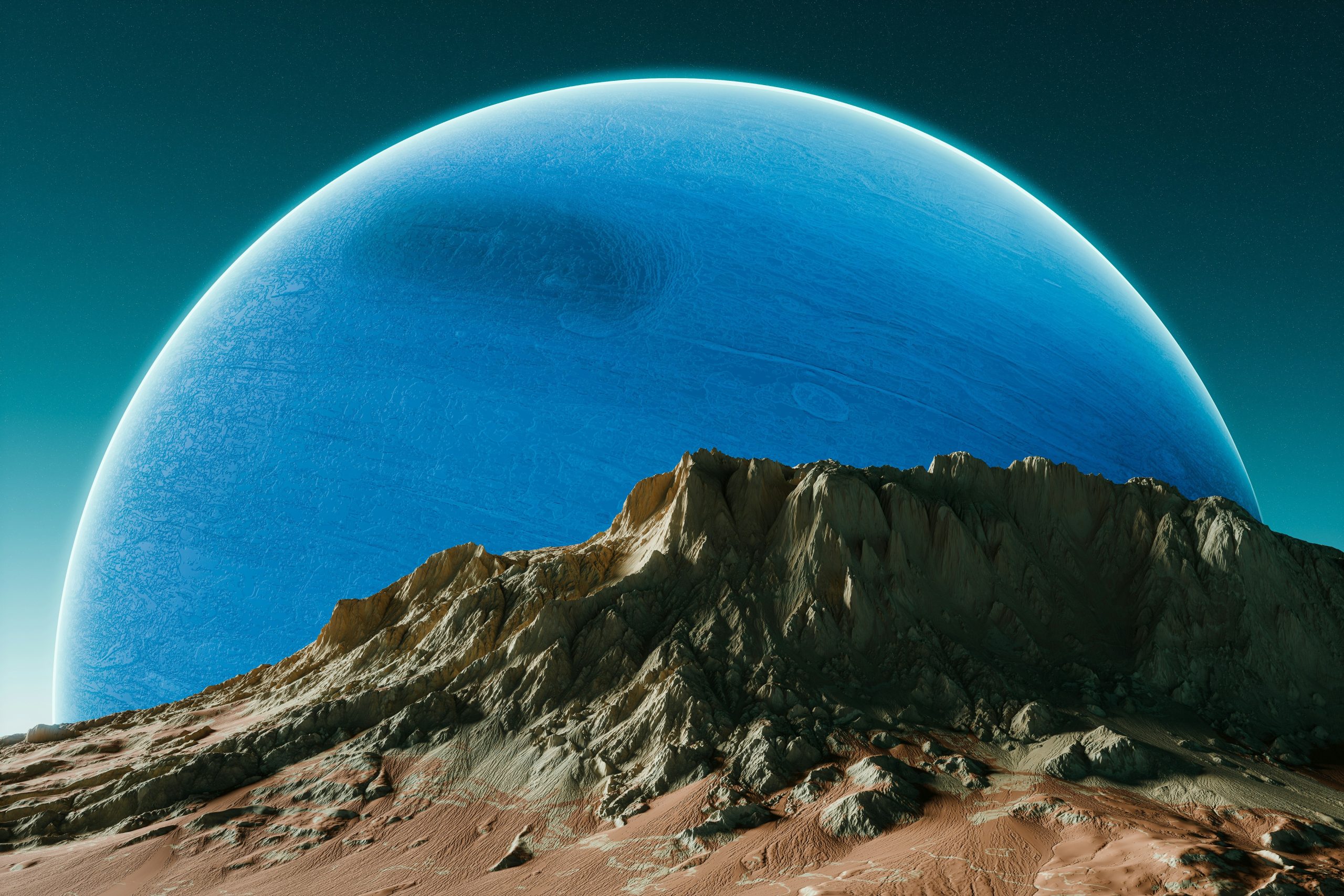

UFOs, recently renamed unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAP), are attracting public attention in the U.S. in a way we haven’t seen for decades. Ex-government officials, prominent politicians, intelligence agencies, major news outlets and civilian scientists are all looking into the prospect of extraterrestrial visitors, making them no longer seem quite so far-fetched.

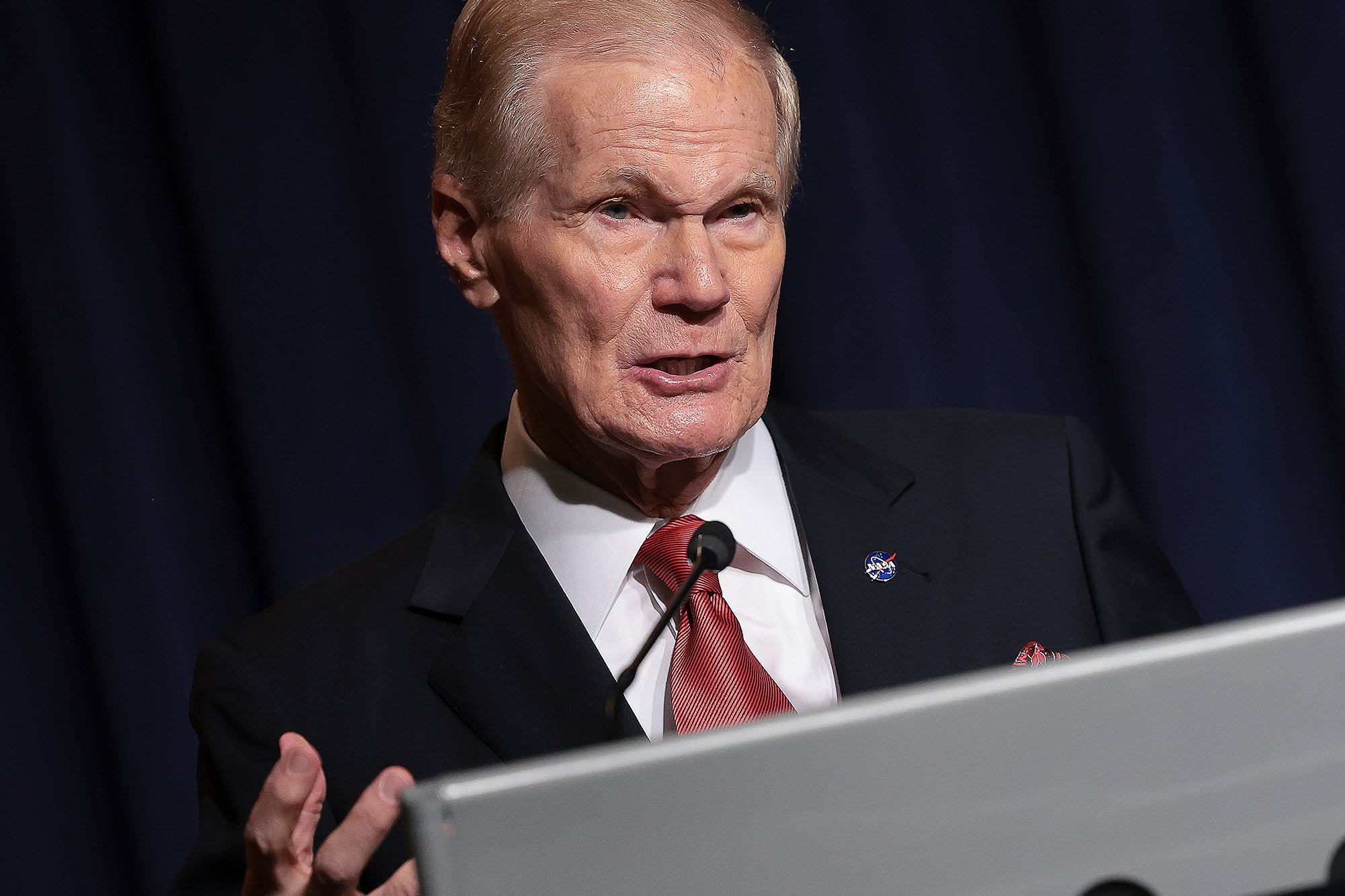

Even NASA, once disinclined to take the subject seriously, convened an independent study team to create a road map for future study of sightings. The team’s final report, which includes this road map, notes there is no evidence pointing to extraterrestrials. However, the questions asked of NASA officials at their recent press conference showed that aliens and cover-ups remain firmly on the minds of many observers.

Not everyone has welcomed the UFOs’ newfound measure of legitimacy in the meantime, and critics have questioned both the science and the money behind the resurgence.

But for all their wrangling, advocates for and against the serious investigation of UAP share something in common: they all focus on the question of whether the phenomenon is something that exists in nature, whether worldly or other-worldly.

We don’t conclusively know if UAP physically exist beyond the mundane, but we do know this: UFOs are social facts. Debate about them is transforming our politics and culture—with effects that are largely overlooked.

Social scientists should weigh in on UAP, now. It is a task for which they are well equipped. They not only offer effective techniques for assessing social change, but for decades, social scientists have been conducting research on such relevant topics as human-technological systems, behavioral factors in manned space travel, public attitudes toward UFOs, and the psychophysical and cognitive aspects of sightings.

To start, there are three pressing issues surrounding UAP that bear serious study and discussion: intelligence, trust and research ethics.

The topic of intelligence turns up in multiple contexts in UAP discussions. For instance, regarding classified military knowledge, much of the current debate and legislation revolves around the reliability of UAP information and how it is handled by government agencies. Given national security needs, what appears to be part of a UFO cover-up may also be explained by mundane organizational failures at the Defense Department, administrations hesitant to poke into those failures, an institutional penchant for secrecy, and finally, plain, old, ignorance. Whatever the case, unidentified flying objects represent a challenge to governmental and military authority. This is because the state is expected to have answers to all possible threats. UAP undermine that guarantee since they are, by definition, unknown.

In addition, the subject of UFOs often evokes talk of a separate, mysterious intelligence that must somehow be behind the sightings. This has led philosophers, anthropologists and psychologists to speculate about alien minds, and there is much to be learned from that. We need scholars to figure out how to talk to a being with a nonhuman mind. But we should also examine our assumptions in thinking about and doing research on such intelligence.

Search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) projects, for example, often work with culturally limited notions of civilizational evolution rooted in 19th-century ideals of persistent technological and moral progress. As a result, astronomers unknowingly tend to rely on language borrowed from the era of colonial conquest (e.g., space as “frontier”), while also appropriating land formerly belonging to Indigenous populations to set up their installations. Scholars have warned about how easily reason falls into anthropocentrism and cultural bias when dealing with the nonhuman.

The UAP debate also has much in common with conversations about the threats of artificial intelligence (AI). Both involve scenarios in which humans may interact with a superior intellect. Aside from the fear of being dominated by an unknown power, the prospect of an alien encounter raises concerns about uncontrollable consequences and crises in our social and political orders.

In reality, AI-based methods will allow us to explore such scenarios in detail. In the near future, large language models promise to help generate intellectual positions and communication that are indistinguishable from human ideas. AI could help to simulate how societies and communities might respond to threatening developments such as first contact. And computational methods already offer social scientists ways to explore large language model–based qualitative data; for example, (social) media data and UAP-related government interaction can reveal sentiments and any related patterns that may have eluded us.

Such rigor is especially needed because the history of UFOs has been defined by disputes over the trustworthiness of witness testimony and limited forensic data of these unidentified objects. Since the first reports of UFO sightings in 1947, people have continued to debate over the quality of the data, a fact that has been underscored by the most recent report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

If in earlier times spiritual authorities have judged the credibility of witnesses reporting anomalous events, today the sciences have increasingly assumed this role—one that is being contested. When it comes to truth and trust, contemporary public communication, especially in the U.S., is characterized by a growing suspicion about established experts. Researchers observe a crisis in confidence in traditional scientific and political institutions.

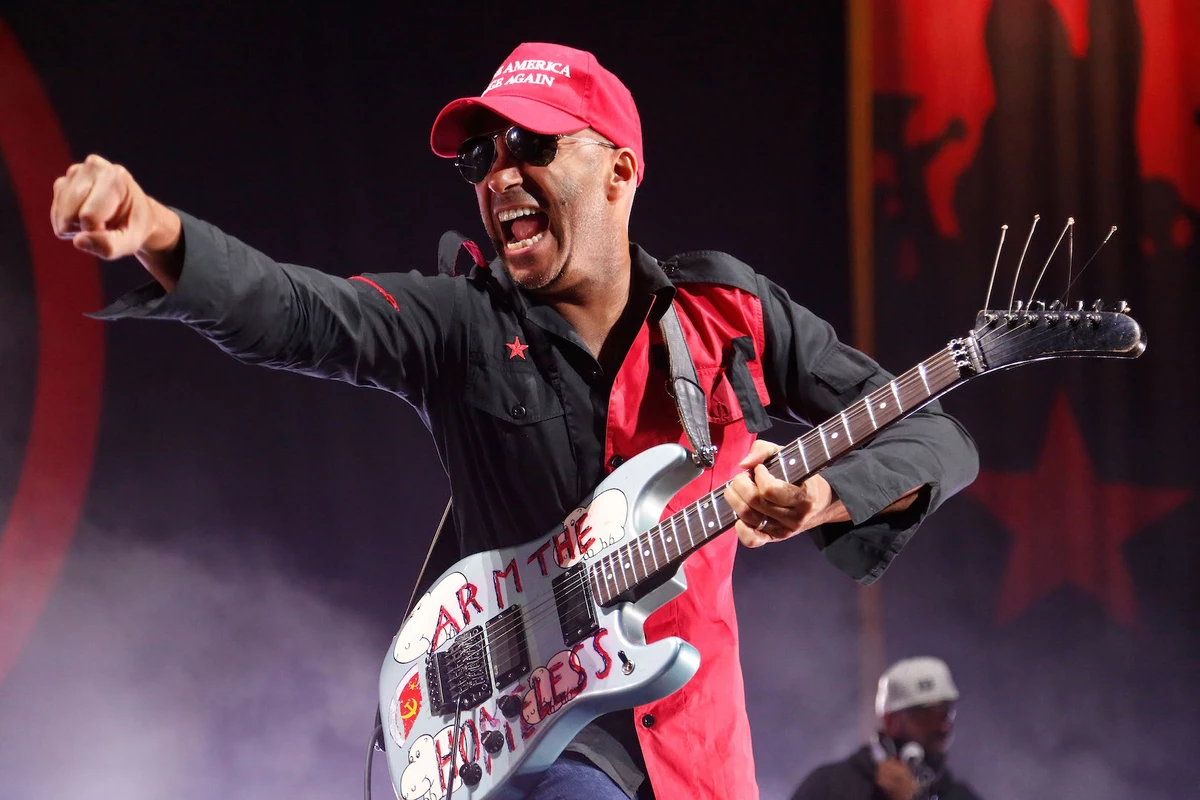

That’s troubling. Yes, questioning authority is admittedly a vital part of a pluralist society. But the spread of unverified “fake news” and conspiracy theories is shown to have corrosive effects on democracy. The circulation of misinformation and disinformation leads people to rely solely on sources confirming their existing beliefs. In the current environment of uncertainty, polarization and suspicion, tangible evidence often gets replaced by symbolic acts of performance to attest to the credibility of claims. This was apparent at the July 26 congressional hearing on UAP, where elected officials suggested an enormous cover-up.

How can we move beyond this? To enhance social trust, experts should lay out responsible standards of research. Deciding how UAP are investigated and by whom raises a variety of research ethics questions warranting reflection.

SETI researchers have already begun weighing the benefits and harms in probing the universe for signs of intelligent life. They have mapped ways to responsibly search for, communicate with and reveal the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations. But they warn that our cultural biases likely make us ill-equipped to respond to such revelations. Caution about built-in bias and failure to account for complexity also apply to computational methods working with large amounts of text and language data. Here again, social science has a role to play.

Barriers to learning are often our own doing. Take the defense and intelligence communities. Both have historically concerned themselves solely with whether UFOs pose a threat to safety. Their default is to frame the UAP matter in terms of security—a view the media often reinforces— thus militarizing the issue. In doing so, they literally classify the matter out of the eye of other policy makers and civilian scientists, as well as the skeptical public.

Putting UAP in the hands of the private sector, however, hardly guarantees greater transparency or conscientiousness. The UFO phenomenon long ago turned into a commercial enterprise, now hyped by streaming services, podcasts, social media and cable television. Its entertainment value has provided the hook for Enigma Labs to promote an app for mobile phone users to report sightings. This raises serious privacy concerns about what this enigmatic company plans to do with the vast amount of users’ personal data it collects. A February RAND report, for example, called for a nationwide way to report sightings. But balancing privacy of both observers and the observed, while making the data transparent to researchers, poses obvious challenges.

Talk about UFOs has never been just about UFOs. The social sciences likely won’t tell us whether UAP are from another world. They will, however, help us explore the “what ifs” and reveal what our actions today tell us about ourselves.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.