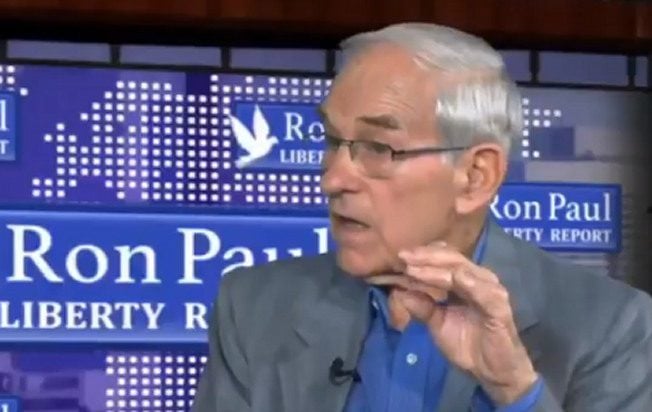

Ted Shepherd, a climate scientist at the University of Reading in the UK, knows what it’s like to arrive at a ski resort only to find that the snow is holidaying elsewhere. This Christmas, he went to Switzerland with his wife and her family. “She always likes to go skiing, but we couldn’t, really,” he says, recalling one resort where skiing was possible at higher altitudes—but people were queuing for 45 minutes either to get the cable car up to the slopes or down again once they’d finished their runs. “It’s just getting worse and worse,” he says of climate change’s impact on European skiing.

In the face of the warm winter season, it’s time for the ski tourism industry to take climate change seriously, says Rob Stewart of Ski Press, a PR firm. “These kinds of unusual weather events seem to be happening more regularly,” he says, recalling how he used to climb and walk on certain glaciers 25 years ago that have since been hit by rising temperatures. “They’re not just melting—they’re gone,” he says.

And although he admits that the skiing community has perhaps been “a bit head in the sand” about climate change in the past, he argues this has changed, and that resorts have little option but to adapt to the changing world in which they operate. But given snowmaking’s need for optimal conditions—and sizable costs—relying on snow guns isn’t necessarily the way forward.

Shepherd points out that in addition to being energy-hungry, artificial snow requires significant amounts of water, a resource that is expected to become scarcer. Plus, there is the sheer cost of running hundreds or even thousands of these machines. Despite recent energy price hikes in Europe, Stewart says ski destinations he has asked about this have not reported financial difficulties associated with snowmaking. Clopath adds that Laax was protected from bill shock thanks to a long-term contract with the resort’s supplier, which fixes its energy tariffs until 2024. “We are hopeful that when we have to buy in 2024, that the prices are going down,” he says.

Other ski resorts, though, are unable to call on Laax’s armies of snowmaking machines, and so are adapting in other ways. Pays de Gex, in the French Jura Mountains, has suffered at altitudes lower than 1,700 meters in recent weeks. Lacking the white stuff, it instead offered travelers mountain biking, paragliding, pony trails, and two new activities—a toboggan on rails and a huge zip line.

“I think it’s the future of this mountain,” says Bruno Bourdat, director of the tourist office, suggesting that the resort will have to get used to offering a range of alternatives when skiing isn’t possible. He notes that Pays de Gex has snowmaking machines, but that conditions don’t always favor their use.

The other solution is simply to ski elsewhere. While the Alps have been tested over the past month or so, there has been very good snow at skiing locations in Norway, Japan, and parts of North America, notes Stewart. In fact, some ski resorts that tend to be especially cold this time of year might actually get more snow in the future, argues Shepherd. The sweet spot for snowfall is in the –10 to –1 degree Celsius range, and warming temperatures may move new areas into this window. “You either move up the mountain to get to lower temperatures, or you move north,” Shepherd says.

The signs that skiing is changing are everywhere, no matter where you look. Even the frequent flying and conspicuous consumption that have—rightly or wrongly—been a stereotype of the pastime might melt away as the industry strives to remain culturally acceptable in the Anthropocene, Shepherd suggests. It could mean a new outlook on nature and how we revel in it.

And ski resorts, no matter the depth of their pockets or the size of their snow cannons, cannot hold back rising tides. As Shepherd puts it: “Just trying to fight the weather, I think, is going to be a losing battle.”