October 7, 2024

5 min read

Still Reeling from Hurricane Helene, Florida Braces for Second Major Storm

Parts of Florida still recovering from Hurricane Helene will face their second major storm in just two weeks

Residents of Pinellas County, Florida, fill sandbags at John Chesnut Sr. Park in Palm Harbor, Fla., on October 6, 2024. Florida’s governor has declared a state of emergency on October 5 as forecasters warned that Hurricane Milton was expected to make landfall later this week.

Bryan R. Smith/AFP via Getty Images

Editor’s Note (10/7/24): This story will be updated as the situation unfolds.

In parts of Florida still cleaning up from Hurricane Helene’s damage less than two weeks ago, preparations are well underway for a second damaging storm, Hurricane Milton.

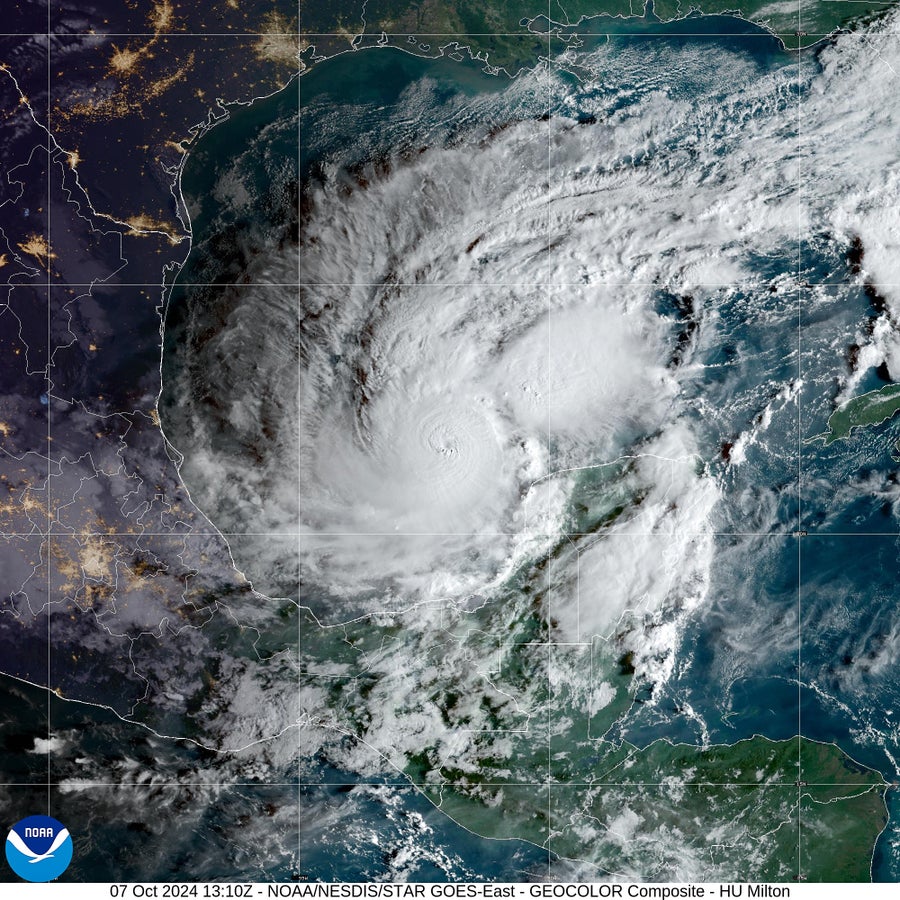

As of 5 P.M. EDT on October 7, Milton is currently a Category 5 storm with 180-mile-per-hour maximum sustained winds off the coast of Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula. It has rapidly intensified and appears to be heading northeast, straight toward the western coast of Florida, with the worst impact currently centered around Tampa. The first of its rains are expected to arrive in Florida late on October 8, with the storm itself making landfall the next day. This may be Tampa Bay’s first direct hit from a serious storm in about a century, although the region, which is home to more than three million people, is no stranger to hurricane damage.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“This is a very serious situation,” says Rick Davis, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service’s Tampa Bay office. “It’s going to affect a lot of people in the state of Florida.”

Milton became a Category 5 hurricane on October 7, 2024, as it continued to intensify over the Gulf of Mexico.

CIRA/NOAA/NESDIS/STAR GOES-East

He says that Hurricane Milton is expected to bring a wide range of threats to west-central Florida: strong winds that could result in power outages lasting up to a week, storm surges of 10 to 15 feet, rainfall totaling five to 10 inches, with up to 15 inches in some locations, and potentially tornadoes. That’s all happening less than two weeks after Hurricane Helene, which made landfall more than 100 miles north of Tampa Bay but still wrought serious damage in the region, including causing the highest storm surge since recordkeeping began in 1947.

Tampa Bay is inherently vulnerable to storm surges because its offshore waters are quite shallow, leaving nowhere for water to go but inland. Moreover, Hurricane Milton is expected to arrive at a right angle and hit Florida’s coast head-on. Whereas an arrival at a more oblique angle can push water along the coast, a perpendicular arrangement causes a steeper surge because it more exclusively pushes water inland. The latter would “pile up water faster and faster and faster and not let it recede,” Davis says.

In addition, Helene stripped the area of local defenses such as sand dunes, leaving the region more vulnerable to future surges. All told, Hurricane Milton could cause twice as much storm surge around Tampa Bay as Hurricane Helene did. (Hurricane Helene killed at least 230 people across the southeastern U.S., including 19 in Florida. A dozen of the latter deaths occurred around the Tampa Bay region.)

The area is also particularly vulnerable to flooding right now, both along the coastline and farther inland. Even before Helene’s hit, the area saw a particularly wet summer, Davis says, leaving the ground saturated and rivers running high. Then came Helene’s surge and downpours; the storm also scattered debris and pushed sand into the area’s stormwater drains, leaving the region even less able to absorb additional water.

Some of the details of Hurricane Milton’s arrival are still uncertain: There’s still time for the storm’s wind intensity and exact path into Florida to change. The hurricane’s intensity is particularly unpredictable because it underwent a process called rapid intensification, during which a storm’s fastest sustained winds increase in speed by at least 35 miles per hour during a 24-hour period.

Hurricane Milton has blown that definition out of the water. “It went from a Category 1 to a Category 5 in 18 hours,” says Kristen Corbosiero, an atmospheric scientist at the University at Albany. “It’s a really scary situation.” According to the New York Times, only two Atlantic hurricanes on record, Wilma in 2005 and Felix in 2007, are known to have made bigger leaps in intensity over a 24-hour period.

As of midday EDT on October 7, the storm’s maximum sustained winds were blowing at 175 miles per hour; the previous morning its winds had been just 65 miles per hour. Climate change is expected to increase the number of storms that undergo rapid intensification. It’s too early to analyze in detail the role of climate change in this specific storm or the season as a whole, but other hurricanes this year, including Hurricanes Beryl, Francine and Helene, also underwent rapid intensification. And like Hurricane Helene, Milton has fed upon the quite warm waters that have characterized the Gulf of Mexico this year.

Another concern is that scientists are already seeing signs that Hurricane Milton is building a new eye wall, the strong winds that form the heart of a storm that surrounds the existing core. Within a day, this process can cause the original eye wall to collapse, giving way to the new structure, which allows the storm’s clouds—and damage—to cover more ground. “What’s really concerning with these types of eye wall replacement cycles is that the wind field of the storm grows bigger,” Corbosiero says.

The specifics are unlikely to significantly change the severity of hazards the region experiences, however, Davis says. And Tampa Bay is known to be particularly vulnerable to serious hurricanes, which it typically experiences only peripherally. “We have been brushed by many, many, many, many storms,” Davis says. But the last time a major hurricane made landfall in the region was in 1921. It hasn’t seen a direct hit from any hurricane at all since 1946. Milton will likely break that trend.

After hitting the west-central coast of Florida, Hurricane Milton is expected to cross the state and then track across the Atlantic Ocean. Bermuda might see effects over the weekend, but the storm is not expected to hit communities in the U.S. beyond Florida. (On October 7 and 8, before Milton reaches Florida, the storm has been forecast to cause four to six feet of storm surge and two to four inches of rainfall in the Yucatán peninsula.)

In Florida, however, the risks are very real. “I just want people to take this more seriously than they’ve taken any other storm,” Davis says. “This will be a storm that people will not forget.”

Corbosiero echoes that concern, especially given the fact that Milton comes so close on the heels of Helene and its damage. “This really does have the likelihood to be the worst disaster in hurricanes in U.S. history,” she says. “It’s that much of a potential dire situation, especially if it makes a direct hit on Tampa or one of the very populated areas along [Florida’s] west coast.”