September 25, 2024

4 min read

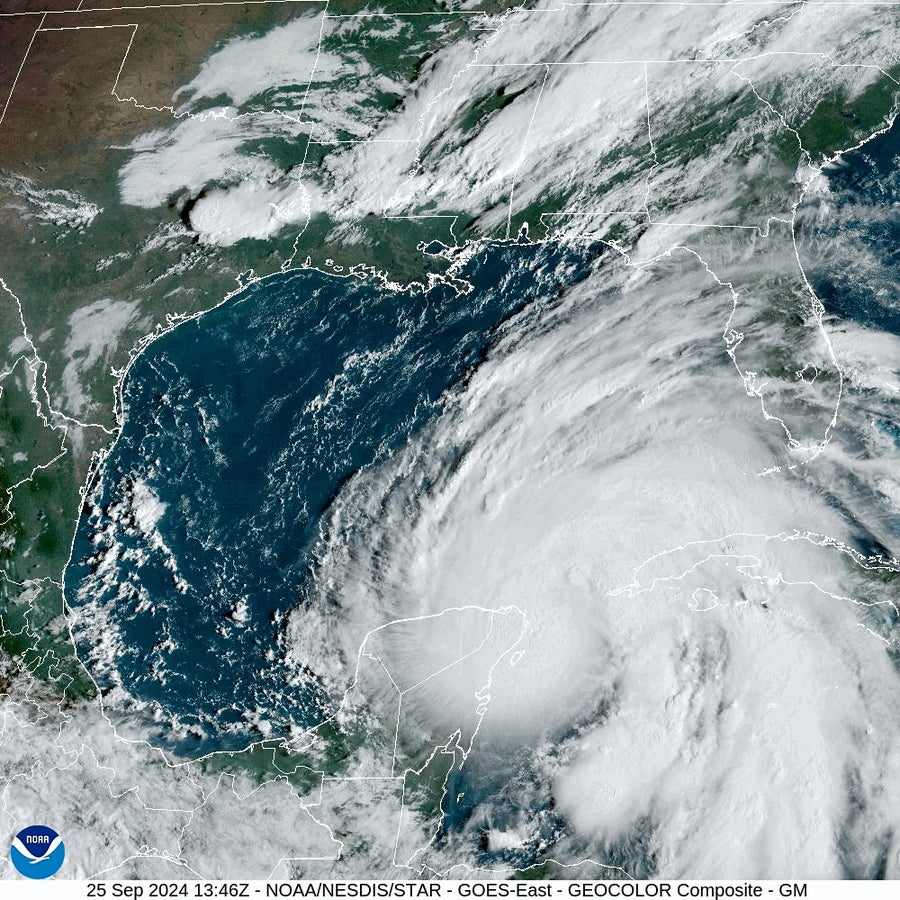

What Makes Hurricane Helene Such a Dangerous Storm?

Hurricane Helene is a large storm set to bring substantial storm surge to the coast of Florida, as well as wind and rain-driven flooding up into Tennessee and South Carolina

A business owner places plywood against a storefront window in Tarpon Springs, Florida on September 25, 2024 ahead of the possible arrival of Hurricane Helene, expected to make landfall on Thursday on Florida’s West Coast.

Hurricane season isn’t done with the Gulf Coast, it seems. Yet another storm, Helene, is heading for Florida a little more than two weeks after Francine walloped Louisiana. Helene is big—and is set to bring up to 15 feet of storm surge in the state. It’s also expected to cause extreme downpours well inland, with the highest potential for flash flooding in the southern Appalachian Mountains.

Though Helene formed just after the mid-September peak of the Atlantic hurricane season, this is still prime time for storms because ocean waters have plenty of heat to fuel them after months of summer sun. This hurricane continues a resurgence in storms that began with Francine in early September following weeks of relatively little activity. The lull came after the season started with a bang with Hurricane Beryl, which became the earliest Category 5 storm on record in the Atlantic basin.

Now Helene is barreling into the Gulf of Mexico, where the environment is expected to be close to ideal for the storm to strengthen. Helene is forecast to become a major hurricane before it makes landfall somewhere in Florida’s Big Bend area (the crook between the state’s panhandle and its main peninsula).

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

One key threat from Helene will be storm surges, which are expected to reach 10 to 15 feet above ground level in the worst-hit areas of the Big Bend. Lower, though still potentially damaging, surge levels are forecast as far away from the center of the storm as the southern tip of Florida. One reason for the large surge footprint will be the storm’s size, which is expected to be in the top 10 percent of hurricanes at similar latitudes.

Helene will be so big in part because “it’s starting out big,” says Kim Wood, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Arizona. Also, the storm’s center is currently threading the needle between Cuba and Mexico; this keeps it over water, allowing the convection that powers the core of tropical systems to continue getting fuel in the form of heat and moisture. Meanwhile the winds swirling around that center are travelling over land, where they encounter friction—“and that moves energy and momentum around” in a way that can increase the size of the storm, Wood says. Lastly, when the storm moves into the gulf, it will have ample moisture and heat, and Wood notes there is some research that suggests that more humid environments yield bigger hurricanes. As an example, they cite Hurricane Katrina, which grew much bigger after it emerged into the gulf than it had been earlier, when it was in the Atlantic to the east of Florida. “The Gulf of Mexico can support bigger storms,” Wood says.

Those warm, moist conditions—along with relatively little wind shear, which can disrupt a storm’s center—are also expected to cause Helene to steadily intensify. It is likely to become Category 3 or stronger before it makes landfall. There’s a strong chance it could undergo what is called rapid intensification, which means a storm’s sustained winds jump by at least 35 miles per hour in 24 hours.

Hurricane Helene over the Gulf of Mexico on September 25, 2024.

NOAA/NESDIS/STAR – GOES EAST

Whether Helene does so depends in part on all of those external environmental factors, as well as the storm’s internal structure. Hurricanes that develop a closed “eye wall” of thunderstorms around their center “eye” can use heat more efficiently and thus grow, Wood explains. This is one reason experts and forecasters are watching detailed satellite imagery that helps them view what is happening at the center of the storm, “almost like an x-ray to see what’s going on underneath the cloud tops,” they say.

Helene’s winds will likely cause problems unusually far inland—with tropical-storm-force winds potentially reaching into northern Georgia—because the storm will be moving fairly briskly. Storms that move faster after making landfall don’t lose energy as quickly, Wood says.

Helene will also bring substantial flooding threats from heavy rains far inland. The areas most likely to be affected extend northward from the Gulf Coast to the southern Appalachians, where the threat will be at its highest. This is partly because that region has been enduring a drought, so the soil is dry and packed. That means much of the rain will simply run off, says Derek Eisentrout, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service’s office in Morristown, Tenn. Additionally, the mountainous terrain means rain can rush down slopes into lower-lying valleys, he says.

Climate change is also playing a role in increasing the threats from hurricanes: Rising seas add to surge amounts, and storms now produce higher rainfall totals than they did in the past. And there is evidence that a higher percentage of hurricanes are reaching the highest intensities, so storms are also expected to undergo rapid strengthening because of climate change.

Forecasters note that anyone in Helene’s path should pay close attention to local forecasts and orders from local officials about evacuations and areas to avoid. Wood notes that the National Weather Service also has helpful Hurricane Threats and Impacts Graphics, which let people toggle between different threats—such as flooding and winds—and click to see the status of their specific area.

Additional reporting by Meghan Bartels.