Just before the launch of a privately built moon lander, partially funded by NASA, the mission is being criticized for a portion of its cargo: the ashes of dozens of people receiving “space funerals.”

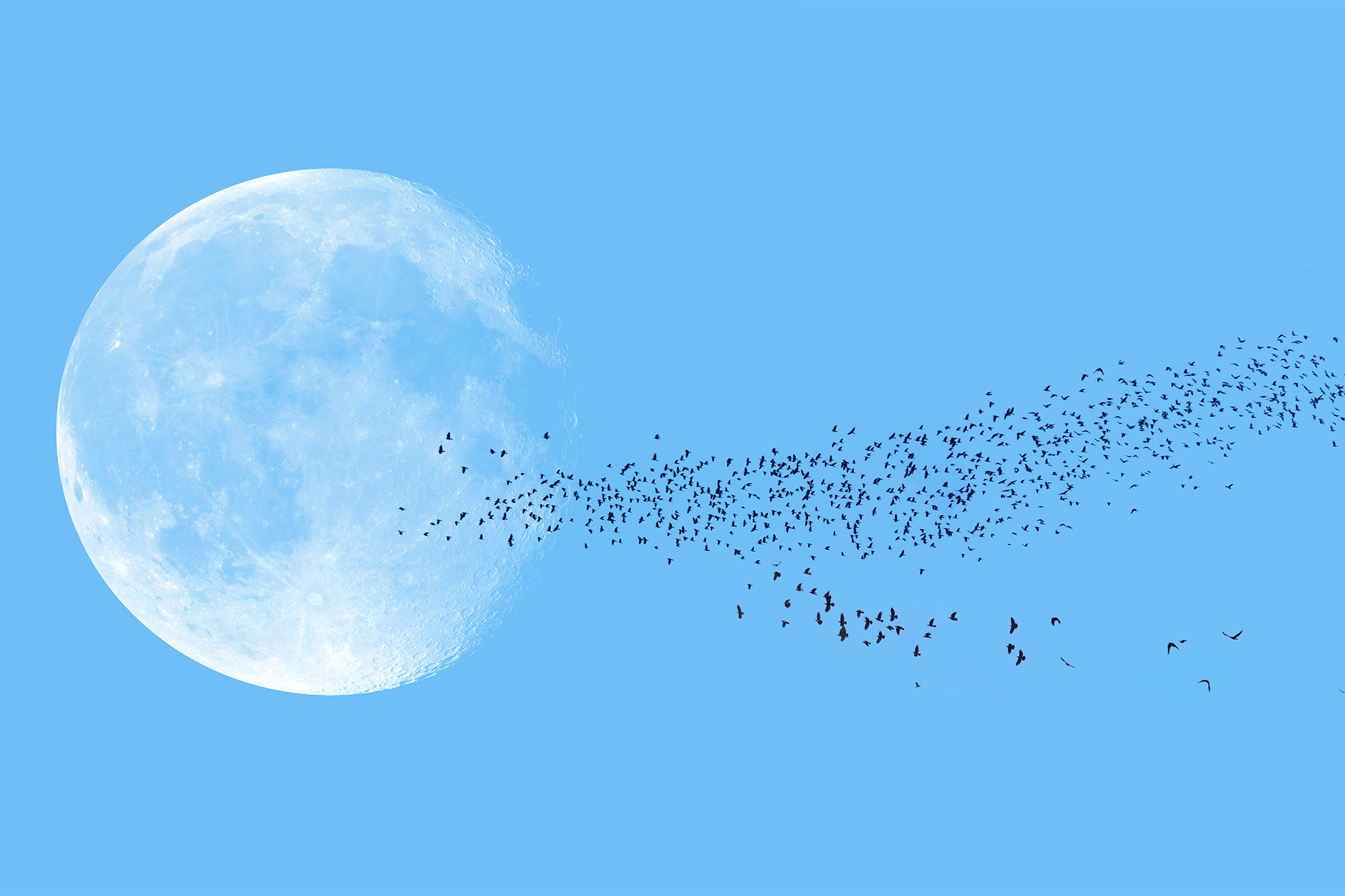

Because of the human remains, the president of the Navajo Nation wrote to the heads of NASA and the Department of Transportation in late December to request that the launch be delayed. The objection lies in the fact that traditions of the Diné (the Navajo people), like those of many Indigenous peoples, hold the moon sacred. Sending human remains there can thus be seen as an act of desecration. The controversy echoes an incident that NASA faced in the late 1990s but with new twists brought about by today’s global, commercially aided moon rush, and it highlights how uncertainties about what can and can’t be done in space are as vast and gray as the moon itself.

“The fundamental principle is that the exploration and use of space is free for all,” says Michelle Hanlon, a space law expert at the University of Mississippi.

Hanlon explains that principle dates back to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), which guides Earthlings’ use of outer space and celestial bodies. But “free for all” doesn’t quite mean “anything goes”: The OST forbids the placement of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction in space, for instance, as well as claims of sovereignty. It also requires that space missions follow international law, help astronauts in distress and show “due regard” for other nations’ space activities. And nations are required to avoid “harmful contamination” of the moon and other bodies—which later guidelines have honed to protecting places, such as Mars and Europa, that might harbor life or its traces.

But that’s about it. International policies regarding spaceflight haven’t evolved much in the intervening decades since the OST’s creation. And even as the commercial sector has rocketed to prominence, regulations have been scarce.

As a commercial, U.S.-based mission, the upcoming moon launch needed a license from the Federal Aviation Administration, which it obtained. But the FAA’s remit is narrow—essentially limited to checking whether a mission jeopardizes the U.S.’s international obligations or poses a threat to public safety or national security. “We don’t have an organization in the United States that is actually making decisions about ‘Are there things that you should and should not be able to send to the moon?’” Hanlon says.

“That’s not necessarily a bad thing,” Hanlon notes, adding that she’s hesitant to overregulate such a young industry. “We don’t need a whole agency process because, really, these are baby steps right now.” But she says that until regulation materializes, complaints like those from the Navajo Nation are a good reminder of the importance of bringing as many voices as possible into ongoing and long-term discussions about what limits—if any—should exist for humanity’s actions beyond Earth.

In the meantime, the spacecraft in question, called Peregrine, as well as its developer and operator, the Pennsylvania-based company Astrobotic, have the chance to become the very first private effort to achieve a gentle lunar landing. If successful, Astrobotic would join only four entities—nation-states all—that have accomplished the feat: the former Soviet Union, the U.S., China and India. And legally, there’s nothing stopping them. “Astrobotic is fully compliant with planetary protection guidelines and adhering to all rules, policies, regulations and laws for commercial space activity beyond Earth orbit,” a company spokesperson wrote in a statement to Scientific American.

As noted, Peregrine was funded in part by NASA, and it carries six of the space agency’s instruments thanks to a NASA selection process that culminated in 2019. (A second mission in the same program is targeting a February launch to also deliver payloads to the moon, but it won’t carry any human remains. It’s not clear which of these two missions will attempt a landing first.) Peregrine’s flight is not a NASA mission, however. The agency merely purchased a ride from Astrobotic, just like the owners of the 15 non-NASA payloads that are also onboard.

“We recognize that some non-NASA commercial payloads could be a cause for concern to some communities, and those communities may not understand that these missions are commercial,” said Joel Kearns, NASA’s deputy associate administrator for exploration, during a press conference. “NASA really doesn’t have involvement or oversight to the other commercial payloads.”

Two of those private payloads carry human remains. These come from U.S. companies Celestis and Elysium Space, respectively. Elysium Space does not provide details about its customers on its website and did not respond to requests for comment from Scientific American. But an image of the capsules during flight preparation suggests that samples from the remains of about 25 people are included in the company’s payload.

Meanwhile Celestis’s payload on Peregrine has materials from about 70 people and one dog. Most are small samples of ashes from cremation, although some are DNA samples, including a few from living people, says Charles Chafer, CEO and co-founder of the company. Among the lander’s “passengers” are prominent science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, Star Trek icons Gene and Majel Roddenberry and NASA geologist Mareta West, who helped select the Apollo 11 landing site. Many others were simply fans of spaceflight, science fiction or astronomy with access to the $12,995 starting price of Celestis’s lunar landing service.

Although the Peregrine mission will mark the first commercial Celestis flight to the moon, one man’s ashes are already on our only natural satellite thanks to the company. In 1998 NASA’s Lunar Prospector launched with onboard ashes of planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker shortly after his death at 69 years old.

Eugene Shoemaker and his wife, the late astronomer Carolyn Shoemaker, had identified about 20 new comets and 800 new asteroids. He also worked on the Apollo missions but had been turned away from the astronaut corps by a medical issue. A close collaborator suggested that NASA arrange for a small amount of his ashes to journey to the moon, and the agency worked with Celestis to accomplish the feat. Carrying those ashes, Lunar Prospector orbited the moon for a year and half before crashing into the lunar surface to create a dust cloud for scientists to observe from Earth.

Albert Hale, then president of the Navajo Nation, objected days after the mission’s launch, however, noting the moon’s sacred status to many members of the community. At the time a NASA spokesperson promised the agency would consult with Indigenous people if it considered a similar memorial again.

After facilitating Eugene Shoemaker’s memorial, Celestis moved on, focusing on missions to low-Earth orbit while the moon languished with few visitors in the early 2000s. But in recent years the moon has become the hottest destination in the solar system, with a host of completed and planned missions from nations and companies alike targeting the lunar surface—and Celestis subsequently reached out to Astrobotic and booked its payload.

Chafer stands by the premise of space funerals. “I think it’s the polar opposite of desecration. It’s celebration,” he says. “I don’t understand why doing that on a dead planet is desecration—where we have literally millions of ash-scattering sites on the living planet Earth, and we don’t consider that desecration.”

But Diné traditions offer a different perspective. “It is crucial to emphasize that the moon holds a sacred position in many Indigenous cultures, including ours,” wrote Navajo Nation president Buu Nygren in his letter, according to Native News Online. “We view it as a part of our spiritual heritage, an object of reverence and respect. The act of depositing human remains and other materials, which could be perceived as discards in any other location, on the moon is tantamount to desecration of this sacred space.” (Nygren’s office did not respond to Scientific American’s requests to provide comment or a copy of the letter.)

Chafer says the request rubs him the wrong way. “I don’t want to question anybody’s religious beliefs, but having said that, what they’re asking for is basically ownership of the moon for purposes of their sacraments, and that’s a giant black hole to walk into,” he says.

Legally, it’s a little more benign, Hanlon says. She notes that attempting to forbid certain moon missions would indeed violate the Outer Space Treaty, which the Navajo Nation isn’t eligible to join or leave on its own but is subject to through the U.S. She explains that the Navajo Nation is requesting only a consultation, not an outright ban, however. On January 4 NASA’s Kearns said that the agency would take part in an intergovernmental team that would look into the issue and meet with the Navajo Nation.

Hanlon sees the call as a good reminder of the value of broadening discussions about who does what in space—and about who decides those rules and what values they prioritize. While space funerals and other personal delivery services can help fund a new commercial-driven era of spaceflight, she notes that if every nation looking to reach the moon takes a similar approach, the results will be grim. “If everybody starts sending stuff up, then the moon is going to get really trashy really fast,” she says.