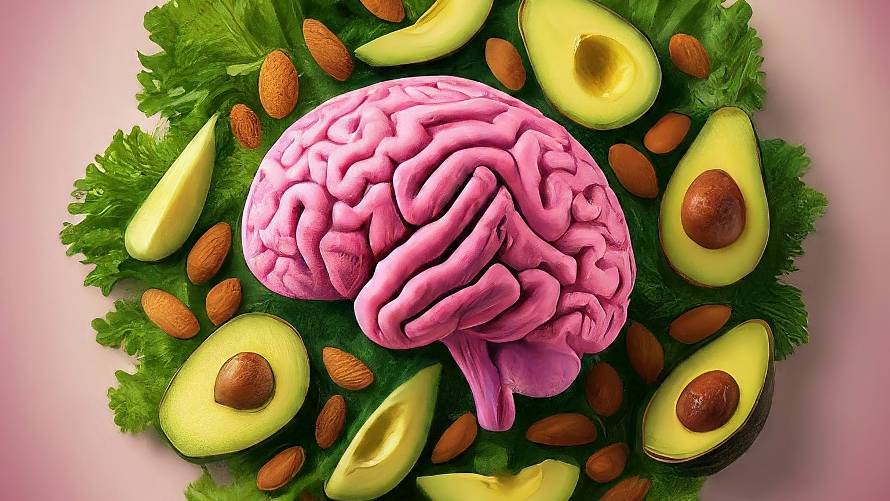

Looking at COVID data in recent months, it may appear that a significant proportion of the people who have died of COVID were vaccinated against the disease. But it is important to put those numbers in context.

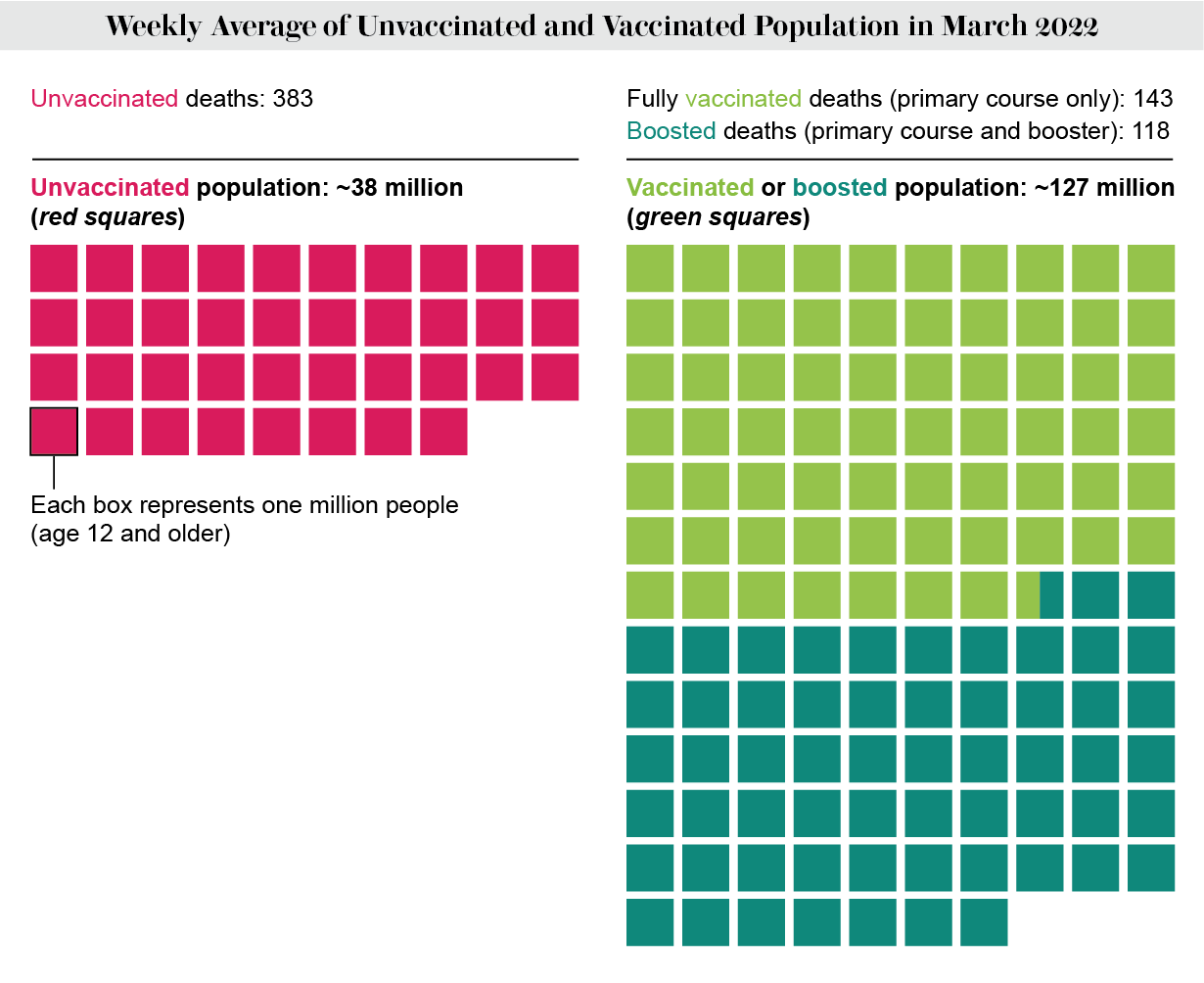

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has compiled data from 28 geographically representative state and local health departments that keep track of COVID death rates among people age 12 and older in relation to their vaccination status, including whether or not they got a booster dose, and age group. Each week in March, on average, a reported 644 people in this data set died of COVID. Of them, 261 were vaccinated with either just a primary round of shots—two doses of an mRNA vaccine or a single dose of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine—or with that primary series and at least one shot of a booster.

Taken at face value, these numbers may appear to indicate that vaccination does not make that much of a difference. But this perception is an example of a phenomenon known as the base rate fallacy. One also has to consider the denominator of the fraction—that is, the sizes of the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations. With shots widely available to almost all age groups, the majority of the U.S. population has been vaccinated. So even if only a small fraction of vaccinated people who get COVID die from it, the more people who are vaccinated, the more likely they are to make up a portion of the dead.

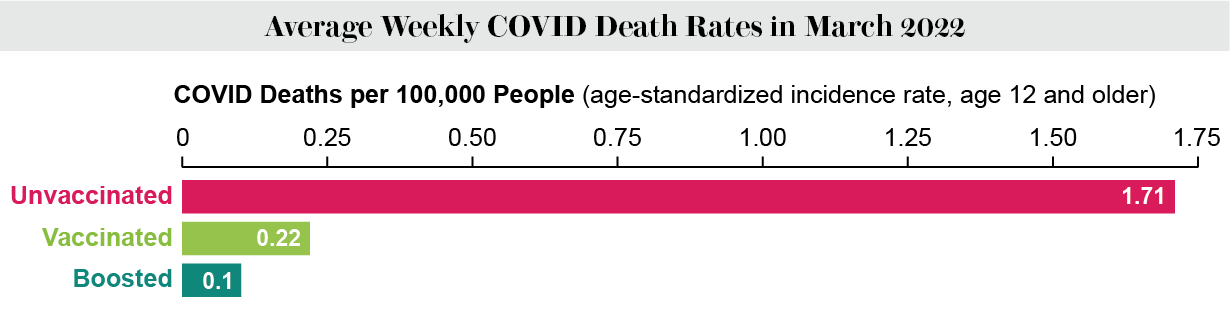

In order to avoid the pitfalls of absolute numbers, it is useful to instead look at incidence rates—usually expressed as the number of deaths per 100,000 people. Standardizing the denominator across all groups offers a very different picture.

Another way to think about the protection vaccination provides is to compare the ratios of death rates among the vaccinated and unvaccinated. For the month of March, “vaccinated people 12 years and older had 17 times the rate of COVID-associated deaths, compared to people vaccinated with a primary series and a booster dose,” says Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service commander Heather Scobie, deputy team lead for surveillance and analytics at the CDC’s Epidemiology Task Force. “Unvaccinated people had eight times the rate of death as compared to people who only had a primary series,” suggesting that boosters increase the level of protection.

It is also important to consider the ages of those who are dying. People 65 and older make up the group that is both the most likely to be vaccinated (and boosted) and the most likely to die of COVID. (Being older is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID because the immune system weakens with age.) So when you separate the age groups, it becomes even clearer that vaccination reduces the risk of death. And because immune protection from vaccination wanes with time, and because some older people do not mount a good immune response to the primary series, being boosted reduces that risk even further.

.png)

An additional factor to consider is that as the pandemic wears on and a disproportionate number of unvaccinated people die from COVID, the unvaccinated population shrinks. This leaves a comparatively larger vaccinated group, leading to an increase in total deaths despite the lower death rate among vaccinated people. No vaccine is 100 percent effective, but immunization reduces the risk of dying from COVID substantially.