In the dense jungles of Cameroon and nearby countries, the population of the iconic and critically endangered western lowland gorilla declined by nearly 20 percent between 2005 and 2013 to about 360,000 individuals—and their number is expected to plunge by another 80 percent over about the next 65 years. Raw materials extracted from their habitat and used for goods manufactured in China and then sold in the U.S. and elsewhere have contributed to that decline. This is just one of thousands of species the world stands to lose as part of the global biodiversity crash caused by human activities, including international trade, which alone drives 30 percent of extinction threats to species.

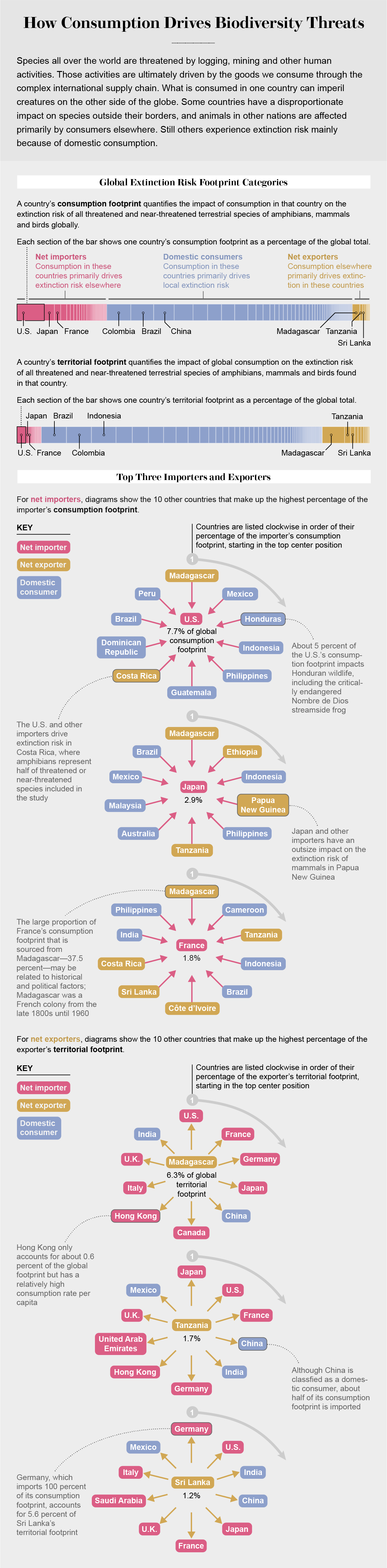

A new study quantifies how the consumption habits of people in 188 countries, through trade and supply networks, ultimately imperil more than 5,000 threatened and near-threatened terrestrial species of amphibians, mammals and birds on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. For the study, recently published in Scientific Reports, researchers used a metric called the extinction-risk footprint. The team found that 76 countries are net “importers” of this footprint, meaning they drive demand for products that contribute to the decline of endangered species abroad. Top among them are the U.S., Japan, France, Germany and the U.K. Another 16 countries—with Madagascar, Tanzania and Sri Lanka leading the list—are designated as net “exporters,” meaning their extinction-risk footprint is driven more by consumption habits in other countries. In the remaining 96 countries, domestic consumption is the most significant driver of extinction risk within those nations.

Amanda Irwin, a Ph.D. student at the University of Sydney, and her colleagues examined global supply chain data, along with IUCN data on species populations and locations. They also consulted the organization’s Species Threat Abatement and Recovery (STAR) Metric, which weighs the scope and severity of threats to species. The researchers then paired those data with computer models of the interactions between different economic sectors. This allowed them to determine the impact of consumption from particular sectors, such as agriculture or construction, caused rapid declines in specific animal populations. “What we’re actually doing is tracing the flow of money through the global economy until we get to the point of what we call ‘final demand’ or ‘consumption,’ which is where you and I spend our money,” Irwin says.

She and her collaborators found that in western Africa, 44 percent of the extinction risk of the western gorilla (predominantly represented by the western lowland gorilla) is exported. This means a substantial amount of the threat to the species ultimately comes from international consumers. The largest single slice of that exported footprint (14 percent) stems from China’s demand for raw materials such as wood and iron. African trees logged in gorilla habitat, for example, could end up as flooring in Asia. The individual percentages for such industries may sound small, but “if we don’t have this understanding of the connection between consumption and production that ultimately happens through these many, many, many interconnected supply chains and flows of money,” Irwin says, “then we’re not in a position to really be able to slow it down at the point of production.”

Other species highlighted in the study include the Malagasy giant jumping rat, a mammal that can jump 40 inches high and is found only in Madagascar. Demand for food and drinks in Europe contributes to 11 percent of this animal’s extinction-risk footprint through habitat loss caused by expanding agriculture. Tobacco, coffee and tea consumption in the U.S. accounts for 3 percent of the extinction-risk footprint for Honduras’s Nombre de Dios streamside frog, an amphibian that suffers from logging and deforestation related to agriculture.

“This study is significant as it provides the first application of the STAR Metric to understand the biodiversity impacts associated with consumption patterns and international trade,” says Alexandra Marques, a researcher at the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, who investigates the causes of biodiversity loss and was not involved in the study.

The study authors say their findings could help consumers, companies and governments make decisions that take species health into consideration. Though this has been done in the past for certain ecosystems such as forests, the new study could help expand the number and type of products that take endangered species into account. Someone buying a dining room table, for example, could look for labels certifying that the wood did not destroy habitat for a specific species. A coffee and tea company could ensure its supply chain does not include products grown in areas that amphibians depend on or that are being deforested for agriculture. Governments could calculate specific industries’ effects on IUCN Red List species in their economic accounting and could negotiate international trade agreements to ensure that biodiversity hotspots are protected.

Even though some countries protect endangered species domestically, people might not realize the outsize impact their purchases have on species in other countries. For example, the U.S.—which accounts for the largest global consumption footprint—has effectively protected endangered species domestically and should extend that effort to other countries, says study co-author and IUCN chief economist Juha Siikamӓki. “We do need to ask whether some of that relative success came at the expense of our creating impacts elsewhere,” he says. And is it sufficient that we only focus on what’s happening in our country if our consumption, in the end, is driving impact elsewhere? We should think about our responsibility in a broader way.”