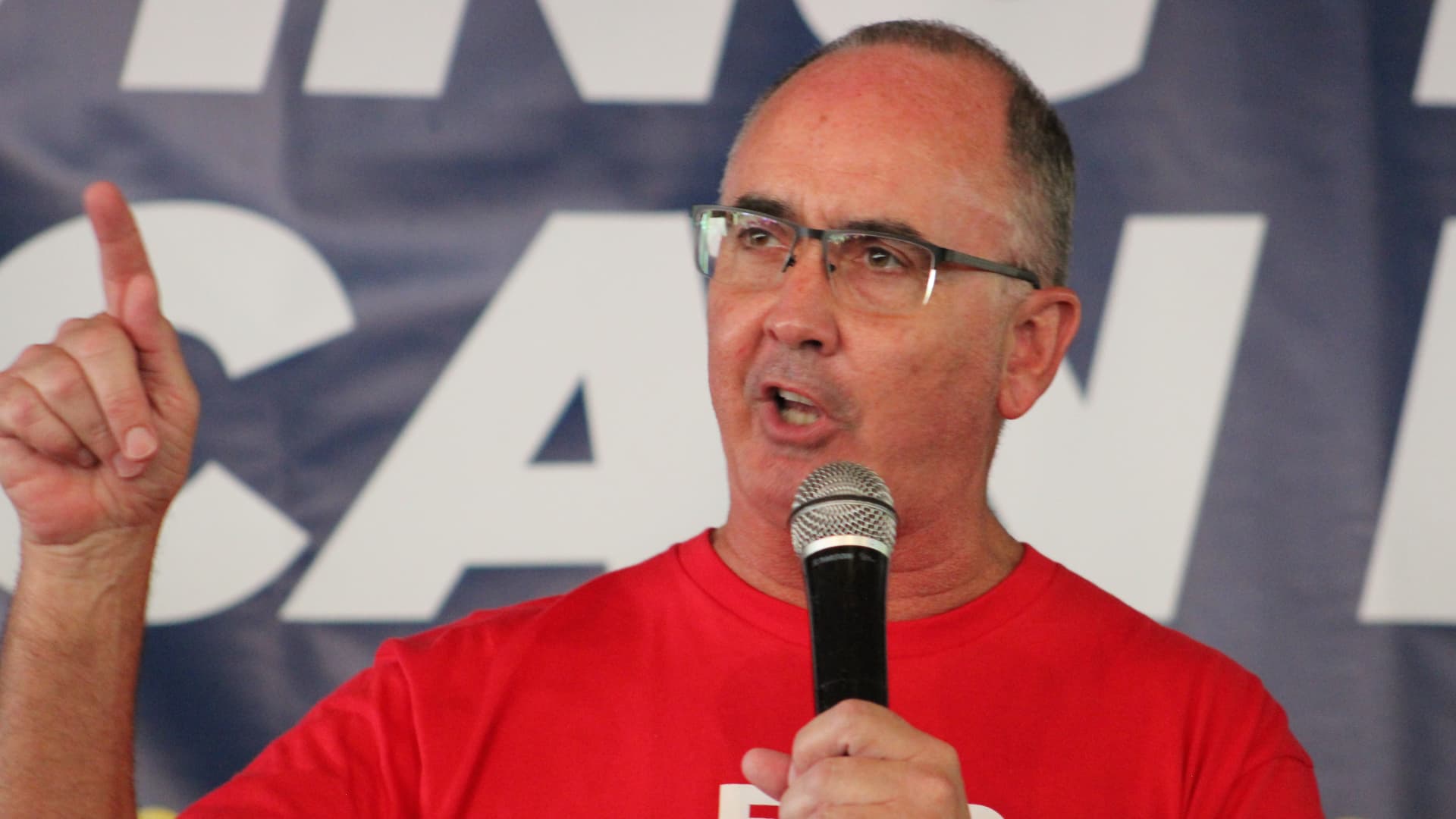

A microscopic image of a metal sphere that a team of scientists argue came from an interstellar object

Interstellar Expedition

Tiny metal spheres found on the seafloor may have come from an interstellar meteor. The researchers that recovered the spherules say their compositions don’t match anything ever seen before on Earth – but it’s a controversial claim.

Earlier this year, Avi Loeb at Harvard University took a team on an expedition off the coast of Papua New Guinea, where models predicted that remnants of an object nicknamed IM1 would have landed. IM1 fell to Earth in 2014. Loeb and his colleagues later identified it as a possible interstellar object based on its recorded velocity, which they claim was fast enough to indicate that it hurtled to Earth from beyond our solar system. They hoped to locate its remains on the ocean floor.

During the expedition, the researchers found about 700 tiny iron-rich spherules. They have started analysing the compositions of those spherules. Of the 57 they’ve examined so far, five seem to have unusual compositions.

These five orbs are particularly rich in the elements beryllium, lanthanum, and uranium, so the researchers have dubbed them BeLaU spherules. The spherules also have particularly low concentrations of elements that scientists would expect to evaporate in the extreme heat a meteor generates as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere. These compositions aren’t consistent with origins on Earth, the moon or Mars, Loeb says.

“Usually when you have spherules that originated from meteors in the solar system, their abundances deviate by, at most, an order of magnitude” he says. These deviate by up to a factor of 1000. “If you combine everything that we know… I’m pretty confident that these came from an interstellar object.”

Loeb says these compositions indicate that the spherules probably came from a differentiated object, one that’s had enough time for the densest elements to sink to the middle. But to some other researchers, that doesn’t track. “These interstellar objects, we expect them to be leakage from the Oort cloud equivalents around other stars… not these differentiated objects that he’s suggesting,” says Alan Rubin at the University of California, Los Angeles. “They’re not what you would expect from interplanetary material.”

Even the idea that these spherules are different from rocks we’ve already found is controversial. “He’d have to compare them to every rock type on Earth and every mineral composition, and then do the same to every mineral and rock from meteorites,” says Michael Busch at the SETI Institute in California. “Even if this mammoth task resulted in a lack of matches, then it still isn’t evidence for an interstellar origin, because meteorites only sample a fraction of materials in our solar system.”

“These are things that have been sitting on the seafloor [for] at least nine years, but frankly probably thousands of years, reacting with seawater and collecting contamination,” says Steven Desch at Arizona State University. “The ocean floor is littered with all sorts of things – there are natural explanations.”

The nature of IM1 itself has come under fire, too. “There’s every reason to think that these velocities, which don’t have error bars, which cannot be checked, are not correct,” says Desch. “For all of the fastest objects that seem to come from outside the solar system, there’s almost always something wonky with the velocity – this object isn’t established as interstellar at all.” Plus, it’s not clear that any material would have survived the meteor’s fiery journey through Earth’s atmosphere, he says.

It will take much more evidence to convince other astronomers that the spherules are truly interstellar. But Loeb says it’s possible that more evidence will be available soon. “We have only analysed one-tenth of the materials, but I decided to put it out now so that we could get some feedback from the community. So if there’s something we need to do differently or if we need to share some materials we can do that,” he says. He and his colleagues are already planning another expedition to look for larger pieces of IM1.

Topics: