A hidden reservoir of red wolf DNA has been found in coyotes in southwestern Louisiana – and it could be used to help the endangered wolves grow their wild population

Life

29 June 2022

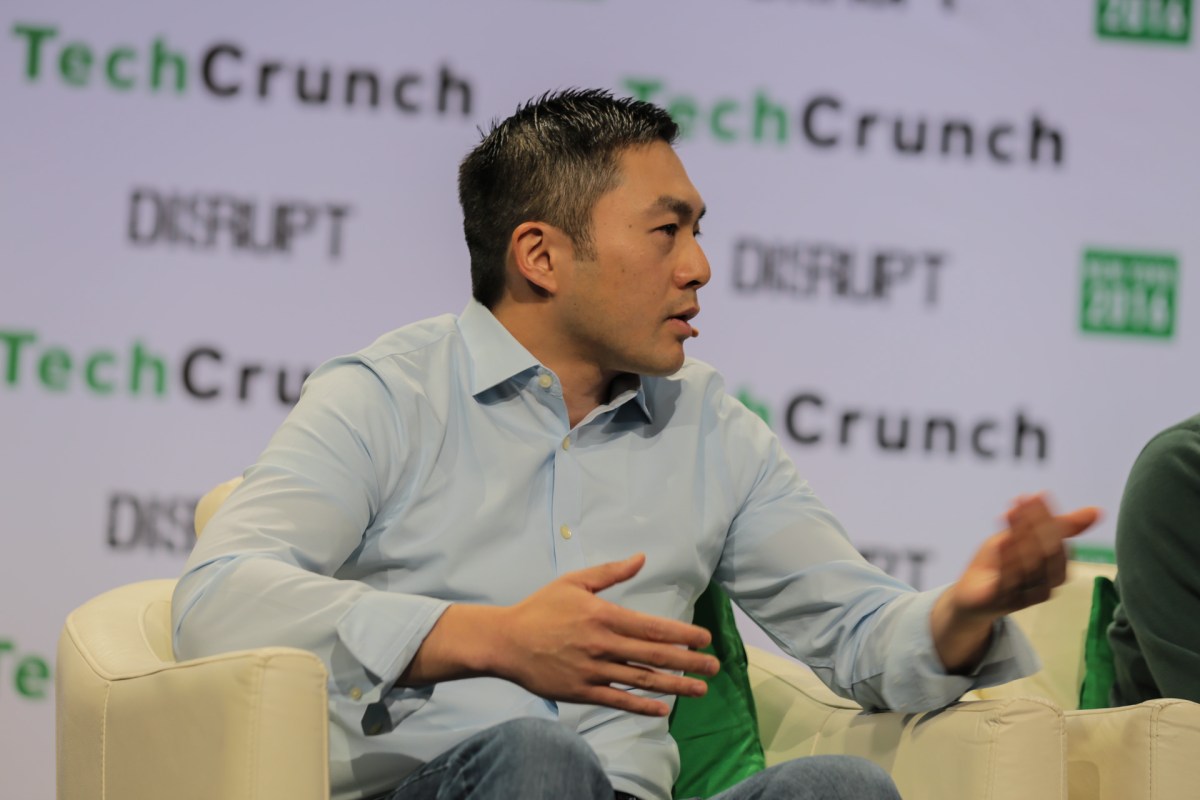

A coyote that is presumed to be a natural hybrid with a red wolf Ivan Kuzmin/Alamy

A genetic reservoir of red wolf “ghost DNA” has been found hidden in coyote-wolf hybrids in southwestern Louisiana. The long-lost genes represent genetic diversity that experts thought disappeared when the last 14 wild red wolves were captured and bred in the 1970s.

Red wolves (Canis rufus) are critically endangered. Just over 200 live in captivity, and only one population was reintroduced to the wild in North Carolina in 1987. By 2012, that population reached 120 individuals, but today only 20 remain.

The rewilded wolves are genetically homogeneous and therefore more vulnerable to harmful genetic mutations, changing environments and extinction. The genetically diverse coyote-wolf hybrids may hold the keys to the species’ survival.

“It’s hard for me to feel anything but optimistic,” says Bridgett vonHoldt at Princeton University in New Jersey.

She and her colleagues sequenced the genomes of more than 30 coyotes from southwestern Louisiana, where red wolves last lived in the wild and where they mingled and mated with coyotes. They found that up to 69 per cent of the genomes originated from red wolves.

The canine chimeras look like intermediates between the two species, but vonHoldt says they behave more like wolves. “I don’t think we should call it a coyote anymore,” she says. “If it looks like a wolf, and it acts like a wolf, maybe we should just call it a wolf.”

The wolf-like coyotes could be the key to conservation. She says that when more red wolves are ready to be reintroduced to the wild, they should be placed close to hybrid carriers of this ghost DNA. Natural matings between the two could increase the genetic diversity of the dwindling gene pool.

Additionally, the researchers are developing biobanks – what vonHoldt calls “frozen zoos” – of coyote cells that could be cloned to resurrect genetic diversity in the natural population. The biobank might also be used to edit red wolf genes back into captive populations, but vonHoldt remains sceptical of that approach.

Samantha Wisely at the University of Florida, who wasn’t involved with the study, says that biobanking can “absolutely rescue a species”, pointing to successful cloning in endangered black-footed ferrets and Przewalski’s horses.

The study fundamentally challenges how we think about hybrids and conservation. “The US Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t have a policy on endangered species hybrids,” says Ben Novak at Revive & Restore, a US biotechnology company. “The red wolves could be pioneering that.”

Wisely agrees that preserving ghost genes from hybrids is groundbreaking. “It’s an innovative approach that really calls the US Fish and Wildlife Service to act,” she says. Protecting the coyote-wolf hybrids is well within their regulatory power, even if they don’t designate them as an endangered species, she says. “I’m not sure if people ever talked about conservation in this way.”

Now, vonHoldt is working with nonprofit organisations and government agencies to translate these findings into policy. “There’s a lot to do,” she says, “but the future is bright.”

Journal reference: Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abn7731

Sign up for Wild Wild Life, a free monthly newsletter celebrating the diversity and science of animals, plants and Earth’s other weird and wonderful inhabitants

More on these topics: