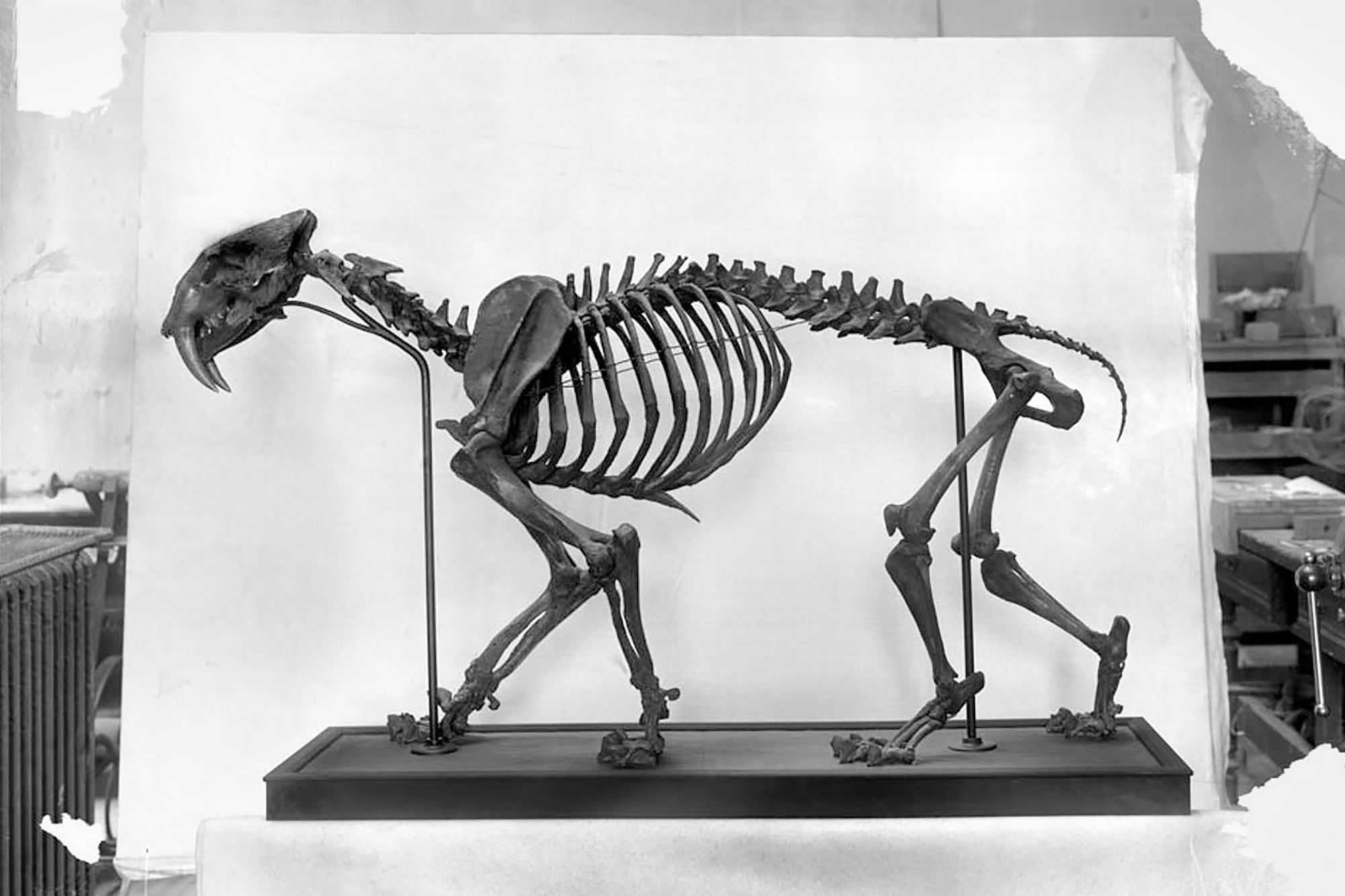

Some 14,000 years ago, downtown Los Angeles was awash with dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, nearly one-ton camels and 10-foot-long ground sloths. But in the geologic blink of an eye, everything changed. By just after 13,000 years ago, these giant animals had all disappeared. What were once lush woodlands had become a dry, shrubby landscape called a chaparral, and large fires were common. What went wrong?

Possible answers to that question come from new research into the famed La Brea Tar Pits published on August 17 in Science. Between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago, naturally occurring asphalt in these “tar pits” trapped organisms ranging from massive predators to hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). The new study shows just how quickly the largest animals disappeared from the La Brea fossil record.

The researchers dated 172 specimens belonging to seven extinct species—the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus), the ancient bison (Bison antiquus), a camel called Camelops hesternus, a horse called Equus occidentalis, the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis), the American lion (Panthera atrox) and Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani)—and the still-living coyote (Canis latrans). The scientists noticed that although the coyote fossils dated anywhere from 16,000 to 10,000 years ago, every other species abruptly disappeared sometime between 14,000 and 13,000 years ago, with the camels and sloths seemingly blinking out a few hundred years before the predators.

“No one in the study was prepared for what we found,” says F. Robin O’Keefe, a biologist at Marshall University and a co-author of the new research. “The coyotes keep being deposited, but the megafauna just, poof, disappear. And for most of them it is like a ‘poof’—it’s a pretty dramatic event.”

To try to understand the fate of these mammals, O’Keefe and his colleagues analyzed sediment cores from a nearby lake that provided data on air temperature, salinity and precipitation. The researchers were particularly struck by a 300-year-long period of high charcoal accumulation from wildfires in the lake that began about 13,200 years ago—right around when the megafauna went missing from the tar pits. “We see these huge pulses of charcoal going into Lake Elsinore all of a sudden, and they’re enormous, compared to anything that happens before that time or after that time,” O’Keefe says. “That’s what clued us in to ‘Okay, the fires are a really important factor.’”

Next the scientists used a computer model to figure out how fires, climate change, species loss and human arrival in the area fit together. And the result is a much more complicated picture of the extinction than that depicted by previous theories, which often blame the extinctions on just one culprit, such as human hunting or climate change. Instead, O’Keefe says, humans likely pushed the ecosystem over the brink by killing off herbivores, which allowed the vegetation that served as wildfire fuel to proliferate just as the climate was drying out anyway and left carnivores without prey.

“It’s not necessarily like massive wildfires drove an extinction of megafauna,” says Allison Karp, a paleoecologist at Yale University, who was not involved in the new research. “It’s that human dynamics changed the fire regime; this interacted with a climate that is arid and at a higher temperature; and this, combined with decreases in herbivore densities, really pushed the system in a nonlinear way and shifted it to another state—a state that included a lot less herbivores and a very different vegetation community and a much higher fire regime than had been seen previously.”

Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecologist at the University of Maine, who was also not involved in the new work, was not surprised that O’Keefe’s team found such a nuanced explanation. “We know that in modern systems, extinction is very rarely unicausal,” Gill says. “You often need to have some force that’s stressing this population. Then there’s often an element of bad luck or some other stressor that comes in. We see that over and over again.”

O’Keefe, Karp and Gill agree that the parallels between today’s headlines and the disappearance of these iconic animals from southern California against a backdrop of wildfires and climate change are eerie.

O’Keefe notes that the research traces a shift from two different ecosystems in just a few centuries. “Mathematically, it’s a catastrophe,” he says. “If the medium of that state shift is fire, and then you look around, and everything’s starting to catch on fire, you start to think, ‘Is it happening again?’ That’s a rational thing to think.”

Understanding how extinctions unfolded long ago, Gill says, can also help ecologists better predict what might happen next today. In that way, they can predict which species, if left to their own devices, are more likely to go the way of the dire wolves or that of the coyotes. “Ecologically speaking, there are winners and losers whenever we have these big upheaval events,” Gill says. “That information helps us to perform the necessary triage that we need to do as we try to save a million species.”