August 28, 2025

4 min read

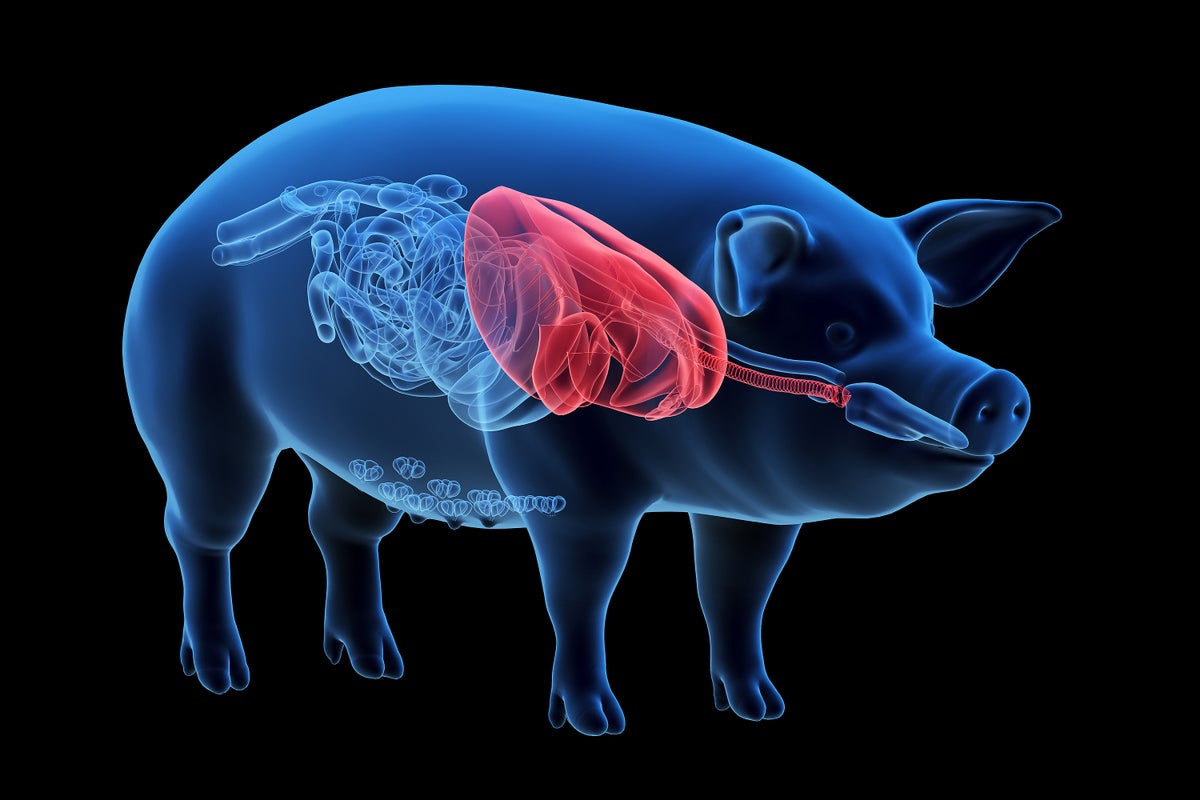

What Does the First Pig-to-Human Lung Transplant Mean for Xenotransplantation?

Surgeons think the first transplantation of a pig lung in a human is an exciting step forward for the field, but many questions remain open

Sebastian Kaulitzki/Science Source

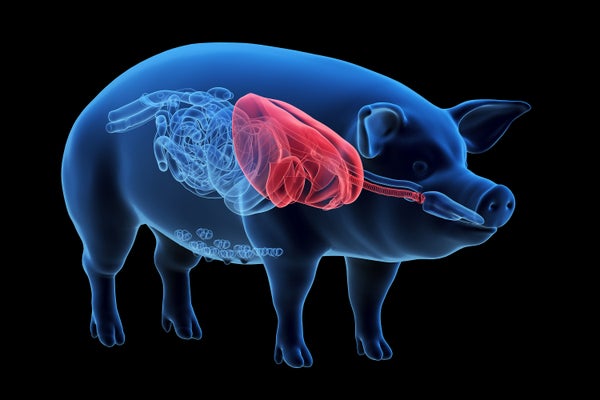

Scientists announced this week that they have managed to keep a genetically modified pig lung alive inside a human body—although briefly—for the first time. The lung survived for nine days, marking what some researchers say is an early step toward a major, long-hoped-for medical breakthrough. But others note that the road ahead is still a lengthy one.

With available human organs constantly filling only a tiny fraction of transplant demand, scientists have been trying for decades to turn pigs into lifesaving donors. Many pig organs are close in size and structure to those of humans, and pigs are prolific breeders that are relatively easy to raise in a pathogen-free environment. Researchers have successfully transplanted pig kidneys, livers and hearts into humans, but lungs have remained a daunting challenge because of their complex physiology.

For one thing, lungs contain many blood vessels and white blood cells called macrophages, which surround and kill bacteria and viruses. These cells rapidly produce immune responses—but they also tend to trigger rapid and potentially lethal inflammation when surgeons restore blood flow after reducing it during transplant surgery. Because of such complexity, “we knew lungs would be the last organ that will get into the clinic,” says Muhammad Mohiuddin, a surgeon and president of the International Xenotransplantation Association, who conducted the first pig-to-human heart transplantation in 2022 but was not involved with the new experiment. And although it “is a great achievement” for the field, “we have to be cautiously optimistic” because this is just an early foray into understanding this extremely difficult procedure.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A team of scientists at China’s Guangzhou Medical University transplanted the pig lung into the body of a 39-year-old recipient who had already been declared brain-dead. The researchers used the gene-editing technique CRISPR to alter three pig genes that are naturally targeted by human antibodies. They also added three human genes to help prevent rejection. From the resulting genetically modified pig, they transplanted the left lung into the recipient, whose body was kept on life support, to observe how the organ functioned and how the human immune system responded. They also administered immunosuppressants to help prevent rejection.

The transplanted lung remained functional for nine days and was not immediately rejected by the human body. The scientists did report signs of lung tissue damage—produced by the lack of oxygen during the transplantation—one day after surgery, however. And the immune system showed the first signs of antibody-mediated rejection on days three and six. The experiment was terminated on day nine at the request of the recipient’s family.

In the study, which was published in Nature Medicine this week, the authors said that the process needs significant improvements, such as optimizing the pig’s genetic modifications and the immunosuppressive drugs used to avoid long-term rejection of the organ. None of the authors responded to Scientific American’s interview requests.

“I don’t think blindly adding more knockouts and transgenes is the solution,” says Columbia University immunologist Megan Sykes, referring to genetic changes to the donor pig. If scientists take that approach, she adds, each modification should be tested separately by transplanting the pig organs into a baboon—a primate that is often used as a prehuman test stop for transplants. Sykes was not involved with the surgery and has focused on pig-to-baboon experiments to establish a recipient’s tolerance of transplanted lungs “I think tolerance, as well as better control of innate immunity, is going to be essential for the success,” she says.

“It would have been nice to see if the lung was able to support life,” says surgeon Richard Pierson of Harvard Medical School, who has also transplanted pig lungs into nonhuman primates. To test this ability, Pierson says, surgeons can block blood flow to a recipient’s existing lung, leaving the transplanted lung to function by itself.

The longest a pig lung has survived after being transplanted into a baboon is 31 days. Pierson, who performed that surgery, says the new one—along with the clinically successful pig kidney transplants—“elicits enthusiasm” in the transplant medicine community. “It reminds us that there’s real progress being made,” he says.

Recent relaxations of countries’ regulatory frameworks has expanded surgeons’ opportunities to experiment with pig-to-human surgeries, making it likely that more such procedures will be attempted in the coming years, Mohiuddin says.

Pig kidney transplants in humans have shown successful results in recent years; these organs have functioned relatively well. Two people are currently living with a pig kidney—one in China who had the surgery in March and another in the U.S. who has had the new organ since January.

The latest preliminary surgery in a recipient with brain death cannot reveal much about the lung’s long-term function, Mohiuddin says. But he adds that it can help scientists test immunosuppressive drugs that do not work the same way in baboon bodies.

Some difficult first steps are needed to advance the development of pig-to-human transplant surgeries that could one day save thousands of lives, according to Mohiuddin. He says he believed in the possibility of making a pig-to-human heart transplantation for decades before he could perform the surgery. “The progress will be slow,” he adds, “but every advance that happens in this field is very critical.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

![[Spoiler] Evicted in Season 27, Week 7 [Spoiler] Evicted in Season 27, Week 7](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/big-brother-live-eviction-week-7.png?w=650)