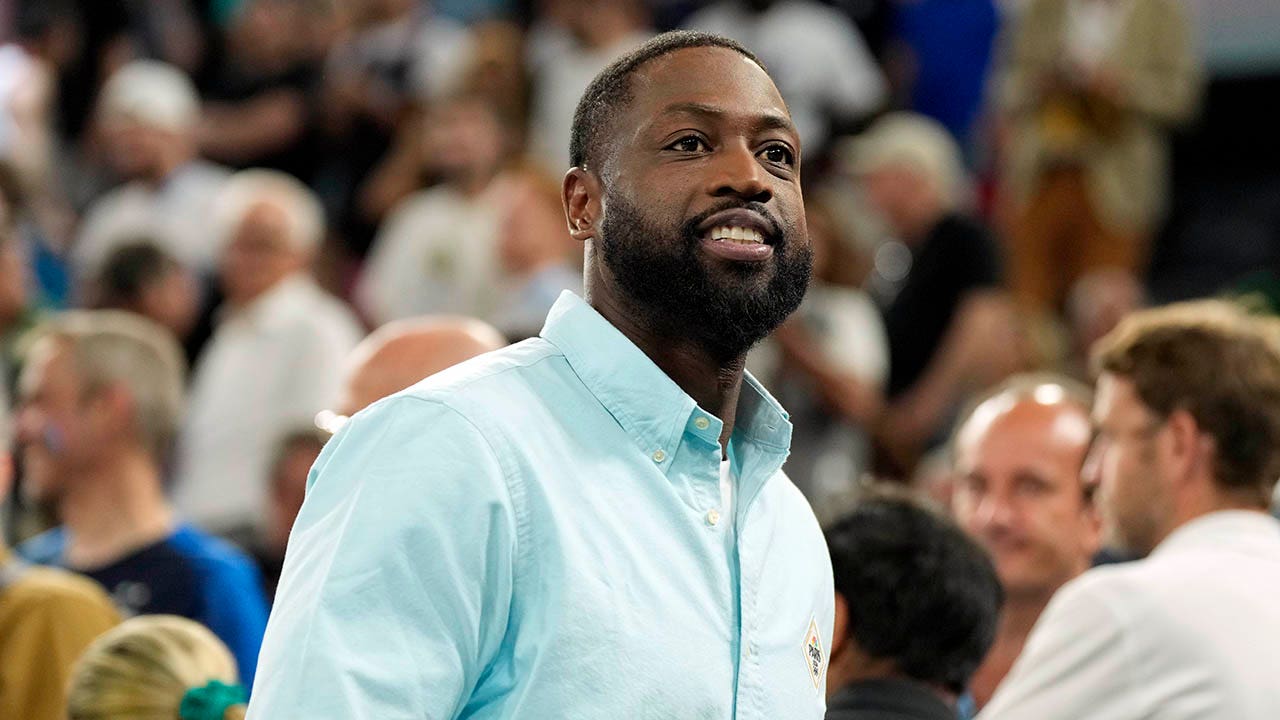

Smartwatches fitted with a new type of transistor could run AI algorithms

LDprod/Shutterstock

A reconfigurable transistor can run AI processes using 100 times less electricity than the standard transistors found in silicon-based chips. It could help spur development of a new generation of smartwatches or other wearable devices capable of using powerful AI technology – something that is impractical today because many AI algorithms would rapidly drain the batteries of wearables built with ordinary transistors.

The new transistors are made of molybdenum disulphide and carbon nanotubes. They can be continuously reconfigured by electric fields to almost instantaneously handle multiple steps in AI-driven processes. In contrast, silicon-based transistors – which act as tiny on-or-off electronic switches – can only perform one step at a time. This means an AI task that might otherwise require 100 silicon-based transistors could instead use just one reconfigurable transistor, thereby reducing energy consumption.

“The low energy results from the fact that we can implement the [AI algorithm] with a 100-fold reduction in the number of transistors, compared to conventional silicon technology,” says Mark Hersam at Northwestern University in Illinois.

Hersam and his colleagues demonstrated how the reconfigurable transistors can help a standard machine-learning-based AI algorithm interpret heartbeat data from 10,000 electrocardiogram tests. The AI achieved 95 per cent accuracy in sorting the heartbeat data samples into six categories, including one “normal” category and five “arrhythmic” categories, including premature ventricular contraction.

Such energy-efficient transistors could prove especially valuable when using AI on devices that either have limited battery life or that cannot maintain a constant wireless internet access to cloud-based AIs running in distant data centres, says research team member Vinod Sangwan at Northwestern University. He pointed to the potential of developing AI-powered wearables such as fitness trackers, temperature sensors and blood pressure monitors.

Running AIs directly on wearable devices without transmitting sensitive health data elsewhere could also help protect data privacy, says Hersam.

But the researchers are still figuring out how to go beyond creating a few reconfigurable transistors for lab experiments. They hope to eventually mass-produce such transistors using standard chip manufacturing equipment.

“While underlying processes are compatible with silicon-based chip manufacturing, there will be other issues to overcome,” says Sangwan.

Topics: