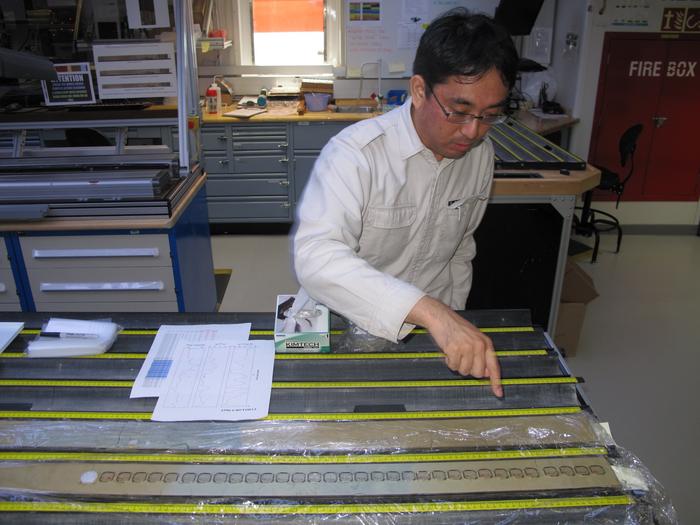

It was on a shift on the drilling ship JOIDES Resolution, somewhere off the coast of Newfoundland in 2012, when Yuhji Yamamoto spotted something odd. The paleomagnetist from Japan’s Kochi University had been reviewing magnetic data from sediment cores hauled up from 300 meters below the North Atlantic sea floor, part of a two-month expedition investigating climate change during the Eocene epoch. Most of the data looked normal enough. Stable polarity pointing one way, stable polarity pointing the other. But sandwiched between them was a thick, messy interval of magnetic confusion that went on for many, many centimeters.

That interval would take years to fully decode. And when Yamamoto and his colleagues finally did, the story those ancient sediments told upended a long-held assumption about one of the most dramatic things our planet does: flip its magnetic field.

Earth’s magnetic poles have swapped places roughly 540 times over the past 170 million years. During each reversal, the field weakens, the poles wander, and our magnetic shield against solar radiation and cosmic particles thins out before everything settles into opposite positions. Based on the best available records (all seven of them, covering less than 1.3 percent of known reversals), the whole process was thought to wrap up in about 10,000 years. Quick, as geological time goes. Now a new study in Nature Communications Earth & Environment documents two Eocene-era reversals from around 40 million years ago that dragged on far longer: one lasting 18,000 years, and another grinding through a staggering 70,000.

“This finding unveiled an extraordinarily prolonged reversal process, challenging conventional understanding and leaving us genuinely astonished,” Yamamoto wrote in a summary of the work.

Peter Lippert, a paleomagnetist at the University of Utah who heads the Utah Paleomagnetic Center and was on that 2012 expedition, recalls the moment his colleague flagged the anomaly. “Yuhji noticed, while looking at some of the data when he was on shift, this one part of the Eocene had really stable polarity in one direction and really stable polarity in another direction,” he says. “But the interval between them… of unstable polarity when it went to the other direction… was spread out over many, many centimeters.” They knew this was no ordinary flip. The team collected extra samples at extremely fine spacing, just a couple centimeters apart, to capture what the sediments were recording in high resolution.

What makes this record so trustworthy is what’s carrying the magnetic signal. Tiny crystals of magnetite, produced by ancient microorganisms that lived in the Eocene ocean, locked in the direction of Earth’s magnetic field as the sediments piled up grain by grain. Like millions of microscopic compass needles frozen in place. The team confirmed through rock magnetic measurements that the magnetite was primary and biogenic, not some later chemical overprint. Over several years of painstaking analysis back in the lab, they constructed high-precision timelines for both reversals, using the rhythmic chemical cycles in the sediment (tied to Earth’s wobbling axial tilt) as a kind of geological metronome.

The longer of the two reversals is the real head-scratcher. It shows all three phases that geophysicists expect during a pole flip, a precursor phase, a main transition, and a rebound, but each was wildly drawn out, and the rebound happened three separate times, the magnetic field lurching back and forth as if it couldn’t quite commit to flipping. Field intensity remained low for the entire 70,000-year stretch. The shorter reversal, at 18,000 years, was still nearly twice the supposed norm.

Here’s the thing, though. Computer simulations of Earth’s geodynamo, the churning of molten nickel-iron in the outer core that generates the magnetic field, have actually predicted this kind of variability for years. Numerical models suggest that reversal durations follow a log-normal distribution, meaning most are relatively brief but a substantial tail of longer ones should exist. Some simulations produce transitions lasting up to 130,000 years. Nobody had caught one in the rocks until now, largely because high-resolution paleomagnetic records older than a few million years are vanishingly rare.

So what does a 70,000-year magnetic reversal mean for life on Earth? Lippert puts it bluntly. “The amazing thing about the magnetic field is that it provides the safety net against radiation from outer space,” he says. A weakened field lasting that long would expose the planet, particularly at higher latitudes, to elevated cosmic radiation for tens of thousands of years. “It’s basically saying we are exposing higher latitudes in particular, but also the entire planet, to greater rates and greater durations of this cosmic radiation and therefore it’s logical to expect that there would be higher rates of genetic mutation,” Lippert says. “There could be atmospheric erosion.”

Whether such prolonged exposure actually left a mark on Eocene life is, for now, an open question. The researchers note that similar prolonged field weakness during the much earlier Ediacaran period has been linked to atmospheric oxygenation and the radiation of complex animal life. Testing whether analogous connections exist in the Eocene is a puzzle that merits further digging. And given that the 10,000-year estimate was built on such a vanishingly small sample of reversals, you have to wonder what other surprises lie buried in ocean sediments we haven’t yet looked at closely enough.

The whole episode is a useful reminder that Earth’s magnetic field, the invisible cocoon we rather take for granted, has an unpredictable streak. We don’t know what triggers any given reversal. We don’t know why some are brief and others protracted. And with 540 pole flips on the books and detailed records of fewer than ten, we are really only just beginning to read the barcode.

Study link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-026-03205-8

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!