Scientists exploring a marine trench near Japan were astonished to find a fish in one of the deepest parts of the ocean, at 8,336 meters (about five miles) below the surface. The tadpole-shaped, translucent creature is a type of snailfish, and it’s probably the deepest fish anyone will ever find.

“They can’t really go any deeper,” says deep-sea scientist Alan Jamieson of the University of West Australia, who led the team that made the discovery. The previous record holder, a juvenile snailfish seen in the Mariana Trench, was filmed at a depth of 8,178 meters in 2017.

Fish withstand the high pressures of extreme depths because of compounds called osmolytes in their cells. Osmolyte concentrations increase at greater depths to ensure that fish cells don’t shrink too much at such bone-crushing pressures, but these compounds reach their maximum concentration at around 8,400 meters. So that’s the theoretical limit of fish physiology. “If anyone does find fish deeper than this, it will not be by much,” Jamieson says.

Ichthyologist Prosanta Chakrabarty, curator of fishes at Louisiana State University’s Museum of Natural Science, is impressed that the fish, a species in the genus Pseudoliparis, could survive so far down, where the water pressure is 800 times that of the surface. “At that depth, everything from gas exchange for breathing to nearly every physiological function seems impossible,” he says. “I can barely swim to the bottom of a swimming pool without my ears popping.”

Jamieson’s team discovered the snailfish in August 2022 at the bottom of the Izu-Ogasawara Trench, near the main islands of Japan. The team was using crewed and uncrewed underwater vehicles to explore deep ocean trenches, and the Izu-Ogasawara connects in the south to the deepest, the Mariana Trench. The deepest parts of the Japanese trench are slightly warmer than the Mariana, reaching about 1.7 degrees Celsius (35 degrees Fahrenheit), Jamieson says.

The warmer water seems to be why the snailfish survive. Osmolytes are less effective at low temperatures, and these snailfish are living near the edge of what’s possible. “The difference is a fraction of a degree, so we wouldn’t care,” Jamieson says. “But it makes a difference to marine animals.”

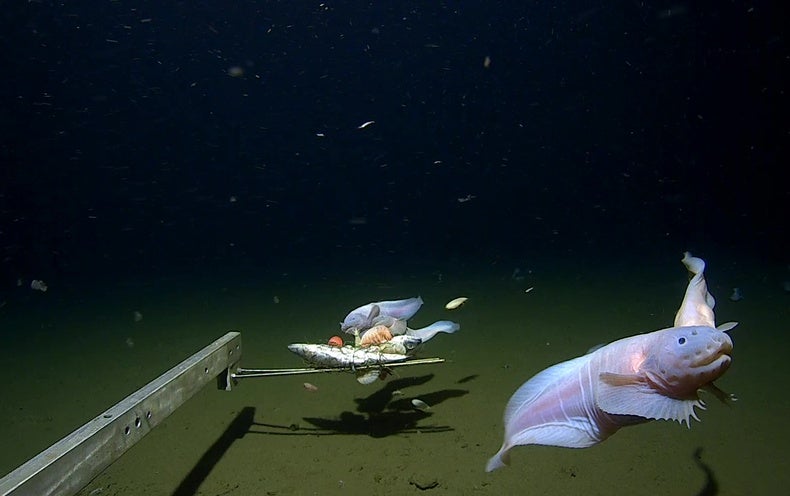

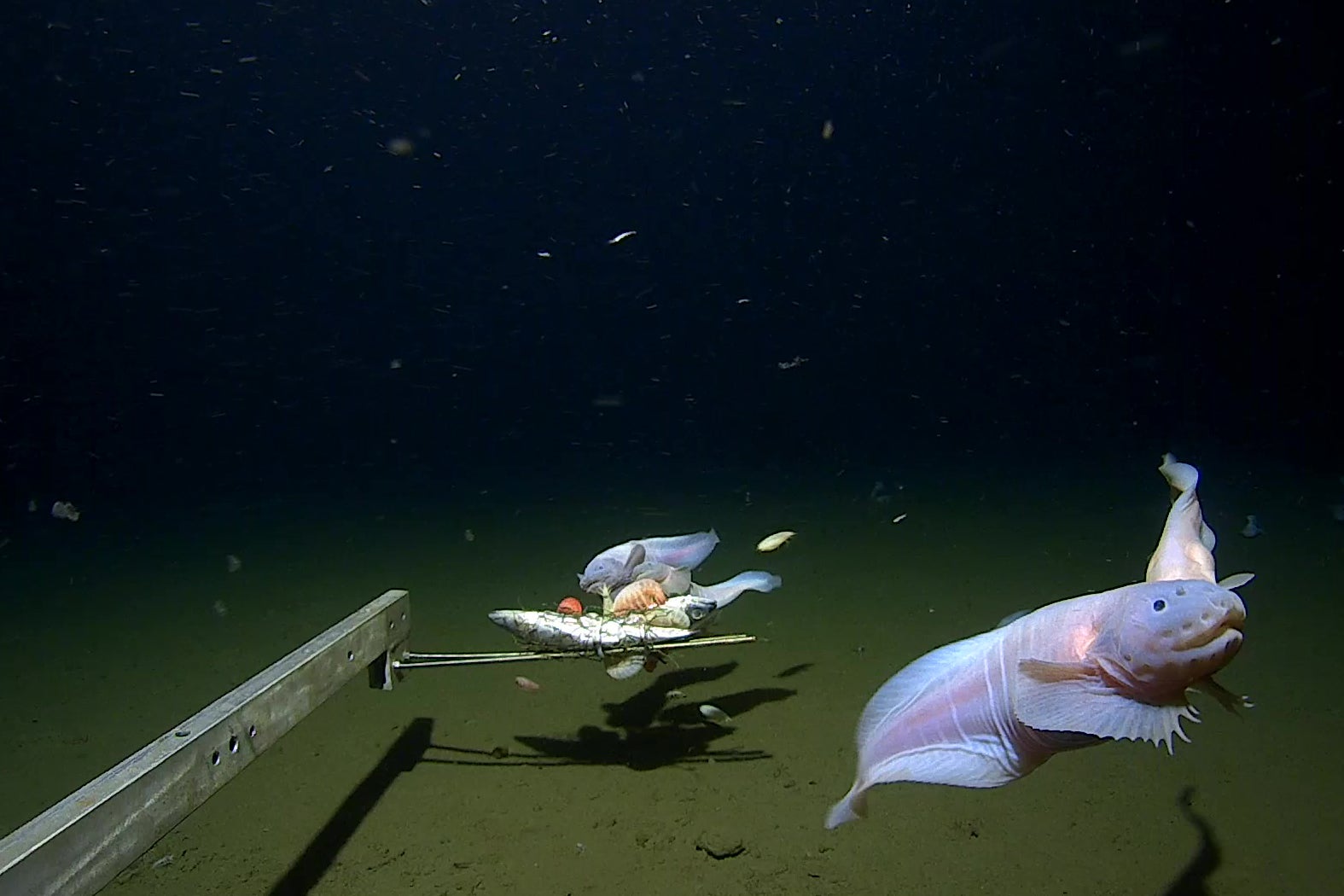

To photograph the fish, researchers onboard the DSSV Pressure Drop sent down a “lander”—an autonomous underwater vehicle equipped with cameras, lights and batteries, along with a weight to carry the contraption to the seafloor.

The researchers used landers that carried dead fish as bait; deep-sea crustaceans ate the bait, and the snailfish came to eat the crustaceans. The lander that made the finding photographed a single juvenile snailfish at 8,336 meters. Though the team couldn’t identify the type of snailfish, two others from the species Pseudoliparis belyaevi were caught in baited traps nearby, at a depth of 8,022 meters.

More than 400 species of snailfish are known from shallow waters to extreme depths, and each species adapts to where it lives, Jamieson says. “Each trench has its own snailfish in it,” he says. “Once they’ve evolved to cope in a trench, they cannot decompress to get from one trench to another.”

In an e-mail to Scientific American, ichthyologist Dahiana Arcila, curator of marine vertebrates at the University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, noted the part played by technology in the discovery. “Rovers and landers [will] gain a deeper understanding of the unexplored regions of our planet’s oceans,” she wrote.