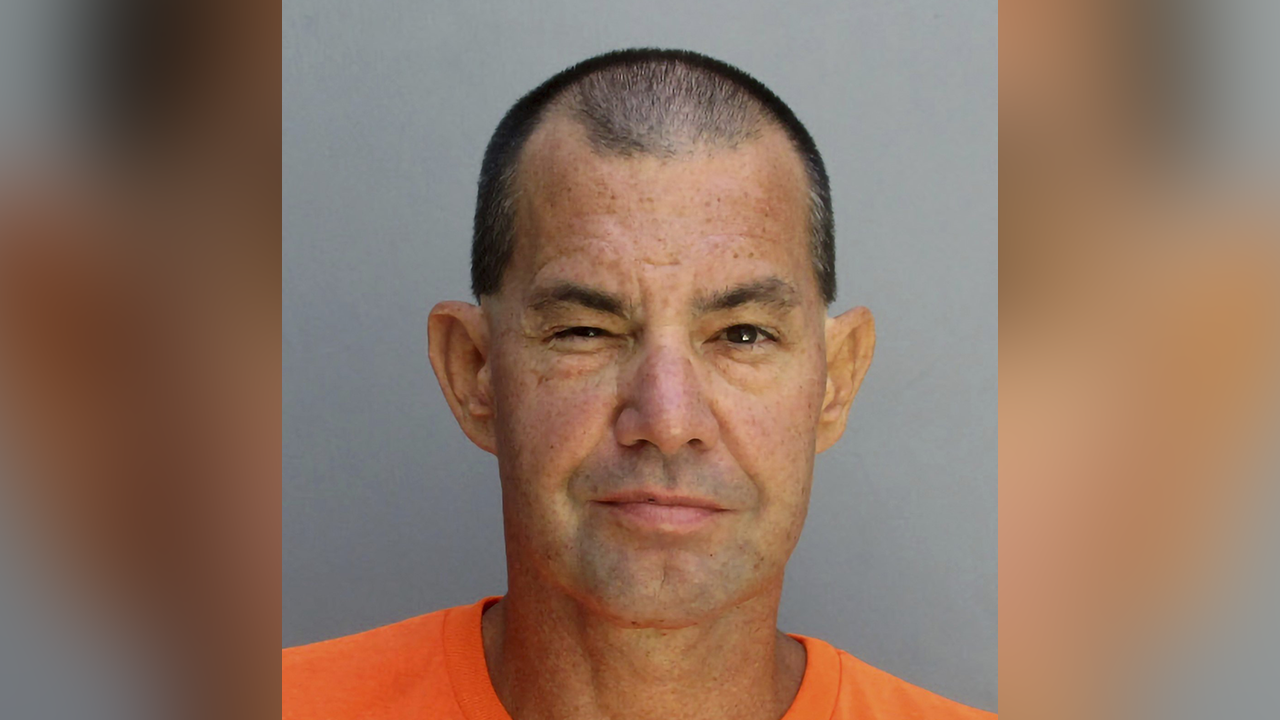

American crocodiles can reproduce asexually

Dasa Petraskova/Shutterstock

A fully formed crocodile fetus has been found in an egg laid by a female that had no contact with males – showing for the first time that “virgin birth” is possible in these animals.

The female fetus – which died at full-term – is a near genetic replica of its mother, a healthy adult kept in an isolated enclosure in a Costa Rican reptile park for 16 years.

Parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction in which embryos develop from unfertilised eggs, is known to occur in some snakes, lizards and even turkeys. The discovery in a crocodile suggests it might date back to a shared ancestor of these reptiles and birds at least 267 million years ago – and suggests that maybe dinosaurs and pterosaurs were able to reproduce without males too.

Workers at the reptile park were surprised when they discovered their individually caged, 18-year-old female American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) guarding a clutch of 14 eggs. Half of them showed shading when held up to the light, as if they contained a fetus.

Because of his expertise in parthenogenesis, the park’s scientific team contacted Warren Booth at Virginia Tech, who suggested they incubate the eggs. When none of the eggs ended up hatching, the team opened them and found that six were filled with unrecognisable contents, probably a mix of yolk and undeveloped cells, he says. One, however, contained a fully formed, but lifeless, female fetus.

Genomic sequencing of tissues from the fetus’s heart and from the mother’s shed skin revealed a 99.9 per cent match – confirming that the offspring had no father and resulted from asexual reproduction.

A crocodile fetus that developed from an unfertilised egg

Warren Booth

Technically, however, the young crocodile wasn’t a clone, says Booth. Like all known cases of parthenogenesis in vertebrates, the embryo formed when the egg fused with one of its own by-products called the second polar body, meaning it had two copies of the mother’s DNA.

The fact that the fetus was female had nothing to do with parental chromosomes, though, since in crocodiles sex is determined purely by outdoor temperatures – and the incubation temperature of 29.5°C (85°F) was just right for forming female fetuses.

The reason why some female reptiles, fish and birds sometimes reproduce asexually remains unclear. But it doesn’t seem to be related to a lack of males, since it occurs even when plenty of males are present, says Booth. “I think it’s controlled by a single gene, which might get triggered by hormones, or something like that,” he says, adding that more research is necessary.

The fetus’s early death doesn’t imply that offspring produced by asexual reproduction can’t live full lives, he adds. Many parthenogenetic offspring in other species live to adulthood and go on to reproduce sexually.

“You wouldn’t believe how many times people send me memes of Jeff Goldblum saying, ‘life finds a way,’” says Booth.

Even so, mammals can’t reproduce through parthenogenesis, he says. Unlike reptiles, fish and birds, their embryo formation requires genomic imprinting, meaning specific genes from both the mother and the father have to switch on and off at specific times to allow the embryo to form.

Topics: