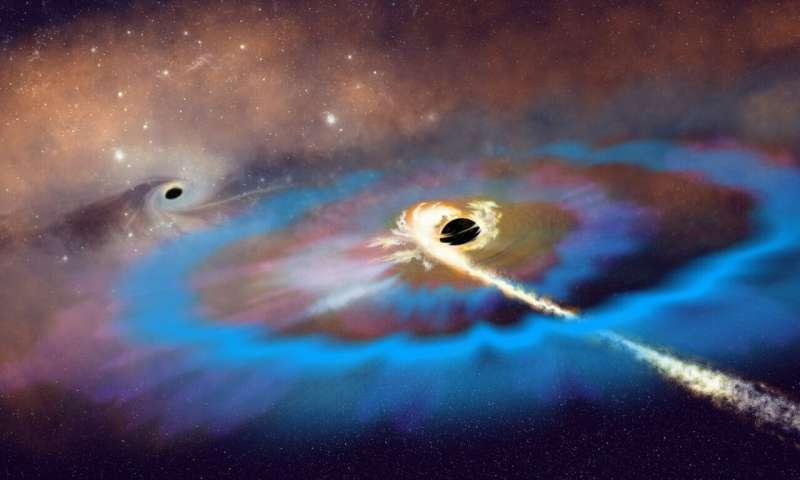

Astronomers have spotted something unusual: a black hole devouring a star far from where black holes are supposed to live. The event, catalogued as AT 2024tvd, happened roughly 2,600 light-years away from its galaxy’s center, and it lit up radio telescopes with signals that changed faster than anything researchers had seen before.

The discovery challenges assumptions about where massive black holes hang out and what happens when they shred passing stars. Most of these violent events, called tidal disruption events, occur right at galactic centers. This one did not.

“This is truly extraordinary,” said Dr. Itai Sfaradi of the University of California, Berkeley, who led the research. “Never before have we seen such bright radio emission from a black hole tearing apart a star, away from a galaxy’s center, and evolving this fast.”

Two Flares, Months Apart

The team tracked AT 2024tvd using an array of radio telescopes, including the Very Large Array, ALMA, and others, starting 88 days after optical telescopes first spotted it. What they found was peculiar: the radio emission showed two distinct peaks, each rising and falling with startling speed. The first flare climbed as fast as a power of nine in brightness over time, then dropped off at a rate of negative six. The second flare was even more dramatic, rising at a rate of 18 before the millimeter-wavelength emission plummeted at negative 12.

These numbers describe the fastest evolution ever recorded for a tidal disruption event. The research team, which included Prof. Raffaella Margutti and collaborators from institutions worldwide, monitored the event across frequencies from 1.5 to 230 gigahertz for roughly 10 months. They watched the radio spectrum change shape as different wavelengths peaked and faded at different times.

The models that best fit the data suggest the black hole did not launch its outflows immediately after tearing the star apart. Instead, the first burst of material seems to have been ejected around 80 days after the initial discovery, coinciding with a change in the X-ray spectrum. A second outflow may have followed about 170 days later, though the team cannot yet rule out that both flares came from the same jet interacting with a complicated surrounding environment.

A Black Hole Out Of Place

The position of this black hole raises questions. Most galaxies keep their supermassive black holes locked at their centers, where they feed on gas and dust funneled inward by gravity. AT 2024tvd sits far from that gravitational nexus, suggesting this black hole is either wandering through the galaxy or recoiling from a past collision with another black hole.

The mass estimate for this black hole ranges from 100,000 to 10 million times that of the sun. If it falls on the lower end, it would qualify as an intermediate-mass black hole, a category that remains frustratingly difficult to study. Only a handful of off-nuclear tidal disruptions have been identified, and AT 2024tvd is the first to produce bright, well-documented radio emission.

Prof. Assaf Horesh from Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose team operated the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager Large Array, emphasized the importance of high-cadence radio observations. “The fact that it was led by my former student, Itai, makes it even more meaningful,” Horesh said. The AMI data proved critical in capturing the rapid changes that defined this event.

The research team explored whether the emission came from a spherical outflow plowing through surrounding gas or from a relativistic jet viewed from the side. Both scenarios remain possible. The delayed launch times favor models where the black hole either spun up its accretion disk slowly or where material fell inward in clumps, triggering separate ejections. The extreme velocities measured during the second flare, which approached half the speed of light, hint at mildly relativistic speeds even in non-jet models.

One intriguing possibility is that the double-peaked radio signal reflects the black hole’s spin axis wobbling as it aligns with the orbiting debris disk. Theoretical work suggests this alignment could take around 193 days for a black hole of this mass, close to when the second flare appeared. If true, astronomers might be watching the system stabilize in real time.

The study also revealed details about the environment around this wandering black hole. The density of surrounding gas appears to drop steeply with distance, steeper than in most other tidal disruption events studied so far. This could reflect the peculiar history of how this black hole ended up so far from its galaxy’s core, whether through a triple black hole interaction or a minor galaxy merger.

What remains unclear is whether the off-nuclear position has anything to do with the unusual radio behavior. The optical and ultraviolet emission from AT 2024tvd looks fairly standard for a tidal disruption, which suggests the radio oddities might just be another example of how diverse these events can be. Then again, researchers have only studied a few dozen tidal disruptions in radio wavelengths, so the sample size is small.

Future observations, including very long baseline interferometry, could resolve whether the emission comes from a jet or a slower wind. Polarization measurements might help too, since jetted outflows tend to show higher polarization near their peak brightness. For now, the team continues monitoring AT 2024tvd as it fades, hoping to catch any late-time surprises that might settle the question of what launched those two remarkable flares.

The Astrophysical Journal Letters: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae0a26

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!