High-quality masks called respirators, such as N95s and KN95s, offer strong protection against the spread of COVID-19. But when it comes to comfort and convenience, there is certainly room for improvement. Masks fog up glasses. Wearing them for hours at a time can get sweaty and uncomfortable (especially in humid summer heat). Efficacy can vary a lot between brands. And when people cover half their face, it’s harder to read facial expressions and interact socially.

This week a project called the Mask Innovation Challenge announced the 10 finalists in a high-prize competition that aims to support innovators working on the masks of the future and to connect these groups with one another.

“We really wanted to help support innovation in order to protect the American public from public health emergencies of the future,” says health scientist Kumiko Lippold, challenge manager of the project. “Together, we really wanted to create something that was comfortable—that you could wear for a long time and ideally not realize—and that also provided superior and exceptional protection that’s based on evidence so that people would understand what they’re wearing and why they’re wearing it and would want to wear it.”

The Mask Innovation Challenge is run by Lippold and her colleagues at the Division of Research, Innovation, and Ventures (DRIVe), part of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. After the competition was launched back in March 2021, nearly 1,500 submissions quickly poured in. To winnow them down to 40 finalists and 10 winners, Lippold’s team and some experts recruited as judges looked at four criteria. First, the entry had to seem like it would feasibly block viruses and work in real-world situations. Second, it needed to be innovative. Third, it had to address issues such as fogging or discomfort, which cause wearers to constantly readjust their mask. Finally, it had to have a strong design that would make people want to wear it.

.JPEG)

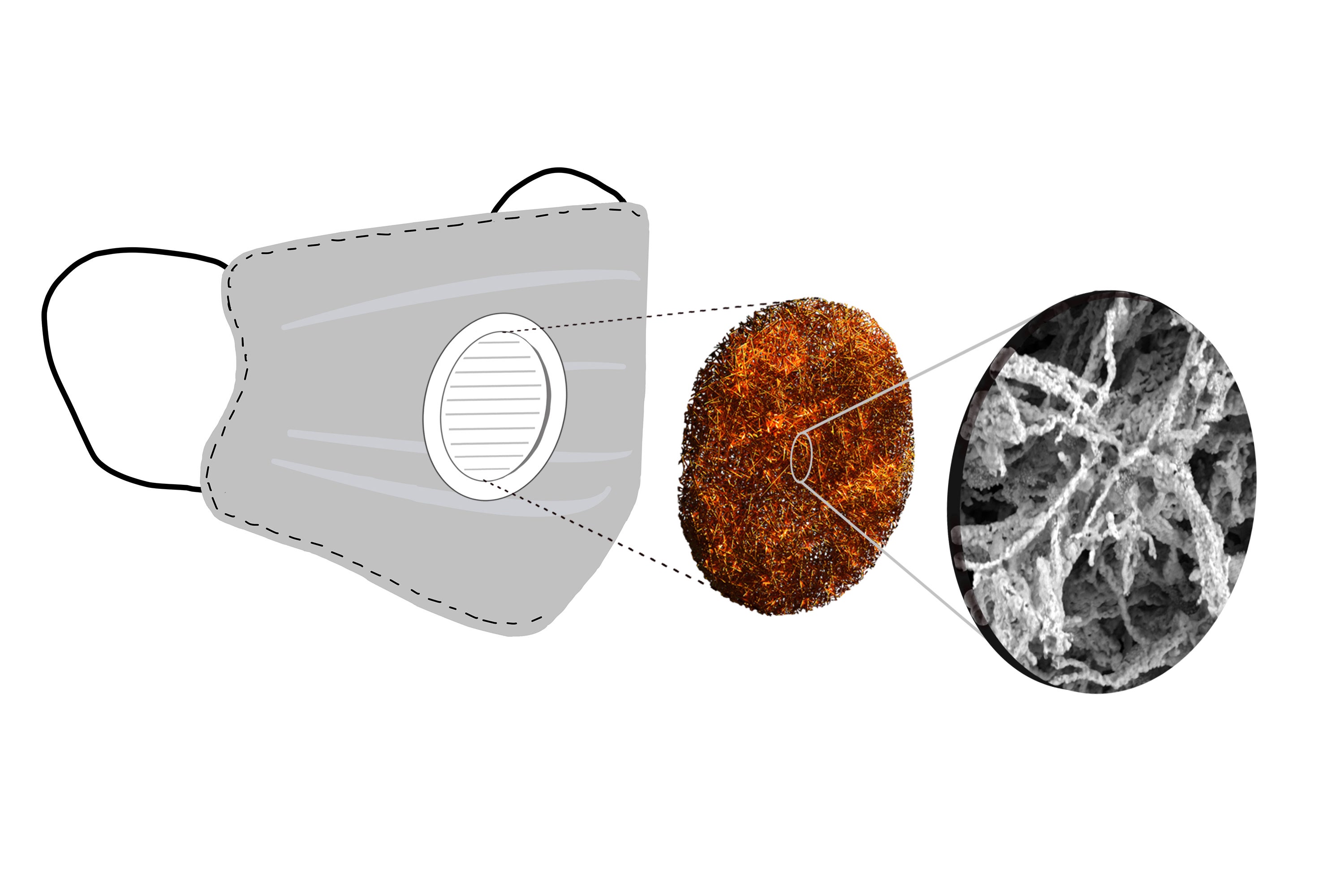

The 10 winning designs varied widely. Most came from start-ups, some originated at universities, and a couple were submitted by major companies, including Amazon. With certain masks, the innovation lay in new materials. An entry from Georgetown University uses light, breathable metal foams that filter contaminants with tiny pores. A start-up called 4C Air created a semi-transparent filter to make its BreSafe Transparent Mask see-through. Other entrants experimented with new fabrication and fitting methods. Jeans maker Levi Strauss developed a low-cost respirator design that the company says any garment producer can manufacture, while start-up Air Flo Labs uses three-dimensional facial scans to ensure its Flo Mask Pro is tailored to a wearer’s face. Some entries broke through by rethinking design elements. These included the Airgami mask from start-up Air99, which incorporates origamilike folds to spread the covering’s filter over a greater surface area, making it easier to breathe through.

But Lippold and her team were not finished. This winners in this initial set were designated as Phase 1 of the contest, and it would take a few months to design a new structure for Phase 2. “We didn’t just want to make Phase 2 a similar exercise to Phase 1. We really wanted to create something that that would meet the needs of innovators,” Lippold explains. “And we did this by engaging with [the general public and] small businesses over time just to really understand what they need.”

For Phase 2, DRIVe reopened the contest: Phase 1 winners could reapply but so could new entrants—and the performance criteria were much higher this time around. “We’ve structured it in a way that really pushed the innovators to achieve very revolutionary changes with their products,” Lippold says. “We weren’t looking for incremental improvements. We were looking for things that were that were really going to move the needle.” In this phase, the DRIVe team partnered with two government organizations, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, to perform repeated laboratory tests of the entries’ filtration efficiency, breathability and fit.

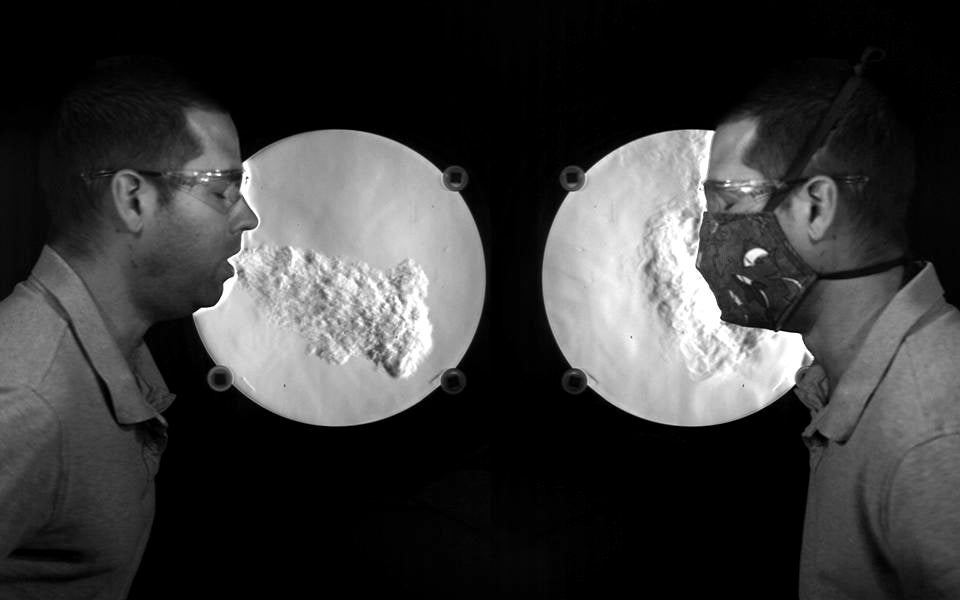

The organizations then provided the results to the competitors, giving them opportunities to revamp and improve their designs. “I got such positive feedback from the finalists,” says Matthew Staymates, a mechanical engineer and fluid dynamicist at NIST. While NIOSH performed quantitative tests, such as measuring the percentage of particles able to force their way through the material and reach the wearer, Staymates focused on more qualitative measurements. For instance, using an imaging technique that makes air flow visible, he recorded himself breathing, speaking and coughing while either unmasked or wearing a challenge participant’s prototype.

Staymates also recorded himself with an infrared camera, which detects the hot air in an exhalation, to demonstrate how much of a mask’s area was actively filtering his breath. And he was not the only guinea pig: he also tested the masks on custom-built mannequins that “breathe” like a human but emit visible fog instead of transparent air. “What I loved about this is that it’s an easy-to-understand visual that confirms what the quantitative NIOSH data is showing,” Staymates says. “And these [mask prototypes] were fantastic. They’re blocking roughly 98, 99 percent of the droplets coming out of the mannequin.”

This week BARDA named the 10 finalists of Phase 2. Of the 10 Phase 1 winners, only the five described earlier made the short list. The five new finalists include three transparent or semi-transparent designs: ClearMask, CrystalGuard and Matregenix Mask. There is also the strap-free ReadiMask, which uses an adhesive designed for skin to stick directly to the wearer’s face and thus avoids air leaks and fogging. And the fifth new finalist is the Smart, Individualized, Near-Face, Extended Wear (SINEW) Mask, which does not even touch the face at all. Instead it uses electrostatic forces to prevent particles from coming near the wearer’s nose and mouth.

These finalists will undergo a final round of testing in September, Lippold says. In October the DRIVe team will announce two winners, who will each receive $150,000, and two runners-up, who will each take home $50,000. But Lippold already considers the challenge a success. “To some extent, we’ve already achieved our goal, which is helping create a community of like-minded innovators that just want to help other people,” she says. “That was sort of an unsaid goal. But we wanted to help inspire and support the acceleration of really novel designs, and I think that we achieved that for Phase 1.”

Her ideal outcome for the next phase would be to help the finalists achieve regulatory clearance, such as N95 certification from NIOSH or approval from the Food and Drug Administration. “By providing the opportunity for testing and evaluation, we help support the generation of evidence based on these masks and how they work,” Lippold adds.

“The Mask Innovation Challenge is good for spurring new designs and innovations and getting new people involved in thinking about how to make good N95s,” says Linsey Marr, an aerosol expert at Virginia Tech, who was not involved in the competition. “We want to make it as easy for people to wear good-quality masks as possible because they are one of the easiest, fastest and cheapest tools we can use to protect against COVID-19 and other diseases. And they are not specific to any particular variant—they work for everything.”