January 11, 2024

4 min read

Traces of an ancient civilization that had a unique urban infrastructure with cities set amid fields have been rediscovered in the Amazon

A complex of rectangular earth platforms of a site called Nijiamanch along the cliff edge of the Upano riverbed in Ecuador.

“Two Thousand Years of Garden Urbanism in the Upper Amazon,” by Stéphen Rostain et al., in Science, Vol. 383. Published online January 11, 2024

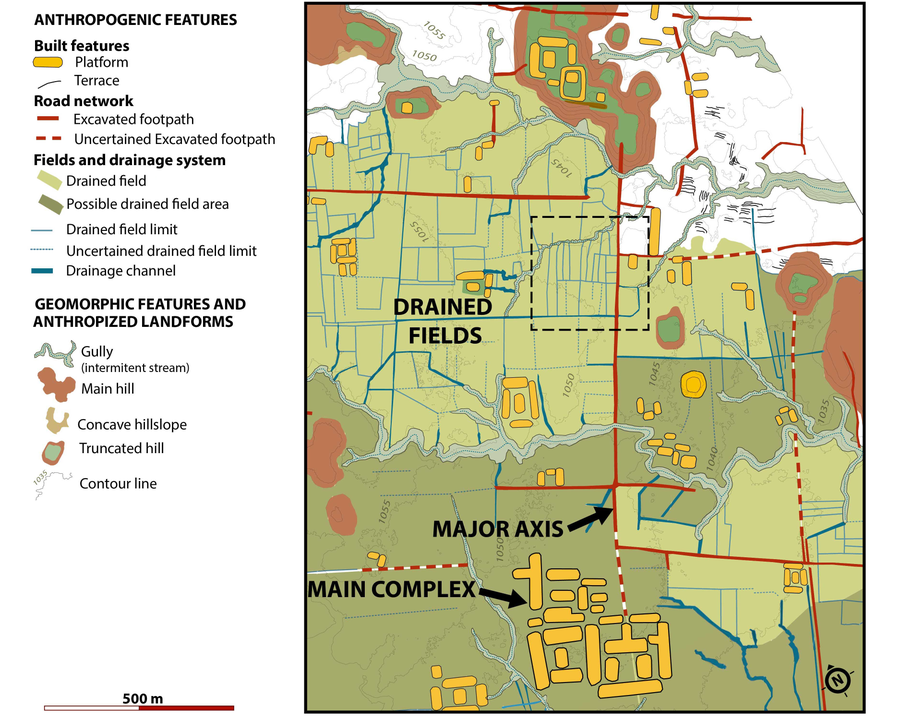

Archaeologists recently rediscovered the long-hidden traces of an ancient Indigenous society in western Ecuador’s Upano Valley: more than 6,000 earthen platforms that once supported houses and communal buildings in 15 urban centers, set amid vast tracts of carefully drained farmland and linked by a network of roads. Stéphen Rostain of the French National Center for Scientific Research and his colleagues say they haven’t seen this unique brand of “garden urbanism” anywhere else in the ancient Americas. It is also the oldest such civilization uncovered in the area.

In recent years researchers have found huge earthen structures, including platforms, mounds and causeways, across the Amazon, from Venezuela to central Brazil. But the infrastructure in Upano, described in a study published on Thursday in Science, “is completely unprecedented in Amazonia and in Andean prehistory,” says archaeologist José Iriarte of the University of Exeter in England, who studies pre-Columbian earth-builder cultures in Brazil and was not involved in the new study. “We don’t see an equivalent to these plazas elsewhere in Amazonia.” The nearest similar urban layout is in Maya territory in Central America.

Rostain and his colleagues pored over data from a 2015 lidar survey of a 300-square-kilometer portion of the Upano Valley. (Lidar works like radar, except it uses pulses of laser light instead of radio waves to measure the distance from an aircraft or tripod to objects on the ground.) The region features fertile volcanic soil nestled against the foothills of the Andes mountains in the shadow of the Sangay volcano. The researchers had previously excavated the tops of some earthen platforms there, at sites called Sangay and Kilamope, where they found the 2,500-year-old remains of houses where people from the Kilamope and Upano cultures had once lived. But the new lidar data revealed a whole landscape of urban centers, farms, roads and canals.

The Upano Valley’s ancient infrastructure is at least 1,000 years older than the other earthworks that have been recently revealed by lidar surveys beneath the Amazon foliage. The civilization likely flourished thanks to what Rostain describes as “a conjunction of good vibes” for a farming society. “I think that its position on the boundary between [the] Andes and Amazonia was very favorable for the development of civilization,” he says. “Because of the Sangay volcano, you have a fertile soil, which is very good for agriculture.”

Each settlement included several groups of platforms, with roads connecting them. Some settlements were small, with just a few house platforms per square kilometer, but others—such as Sangay, which overlooks most of the valley—packed more than 100 platforms into each square kilometer of a site the size of Central Park. And these larger, denser urban centers boasted taller, wider platforms that probably once held communal buildings where people might have gathered for rituals, shared work or social events, Rostain and his colleagues suggest.

A network of roads linked Sangay and other major centers such as Kilamope to one another. These remarkably straight roads tended to be dug two or three meters deep into the landscape and were bordered by tall curbs of piled earth.

Although the roads stand out most dramatically in the lidar images—and reveal the organization, complexity and engineering skill of the Kilamope and Upano societies—fields would have dominated the ancient landscape. Nearly all the open space between communities would have been covered with hundreds of hectares of fields, bordered by shallow drainage ditches that fed into deeper canals. That close link between the fields and the urban centers of the Upano Valley is a unique hallmark of the landscape and the people who built it. Rostain and his colleagues call it “garden urbanism.”

“In between the living areas are agricultural areas and garden spaces. It’s a very dispersed, very extensive concept of city,” Iriarte says. “It is very different from this compact, bounded space with a hinterland that we see in the typical Eurasian perspective of the city.”

The artifacts that Rostain and his colleagues excavated from the house platforms suggest that people built this complex network of communities around 2,500 years ago and abandoned it sometime between C.E. 300 and 600. Rostain thinks “perhaps a series of eruptions could have made trouble for the people, because after [C.E.] 600, we don’t have any archaeological dates until [C.E.] 800.”

Around C.E. 800, a group of people from the Huapula culture moved into the Upano Valley, possibly lured by the prebuilt infrastructure but likely mostly by the fertile volcanic soil. Even today, locals proudly tell the study researchers that they get three good harvests of maize a year from their fields. So the Huapula settled on the same platforms that the Kilamope and Upano had built millennia before, farmed the same fields and walked along the same roads.

By the time European colonizers arrived in the Amazon basin, the forest had hidden what was once a populous landscape with bustling communities and carefully engineered infrastructure. But the marks left behind by these ancient civilizations never really faded from the landscape.

Rostain and his colleagues are investigating how far the Upano Valley’s garden cities extended beyond the 300 square kilometers of the survey area. They’re also interested in how the people of the Upano Valley might have interacted with cultures on the far side of the Andes. Iriarte expects that future lidar surveys will show that earth-building cultures in far-flung corners of the Amazon were connected by trade across great distances.