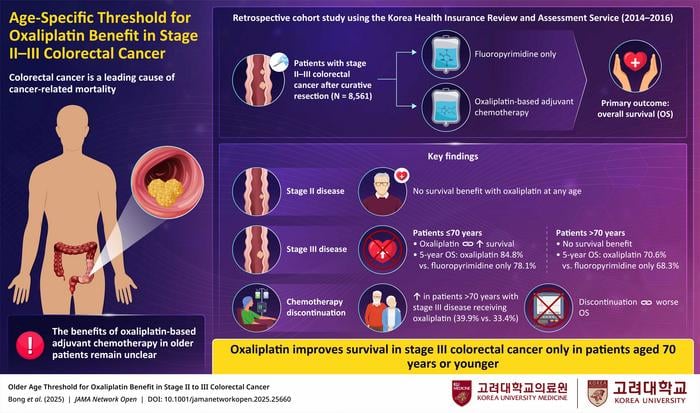

For decades, oncologists have wrestled with a fundamental question: when does aggressive chemotherapy stop helping and start harming older cancer patients? A massive Korean study tracking 8,561 colorectal cancer patients has delivered a surprisingly precise answer – age 70 marks the cutoff where a standard chemotherapy drug loses its lifesaving power.

The findings, published in JAMA Network Open, challenge current practices and could reshape treatment decisions for thousands of patients annually. Researchers analyzed national health records spanning three years to determine whether oxaliplatin, a cornerstone of colorectal cancer treatment, provides survival benefits across different age groups.

Their conclusion was stark. In stage III colorectal cancer patients aged 70 or younger, adding oxaliplatin to standard chemotherapy reduced death risk by 41%, boosting five-year survival rates from 78% to nearly 85%. But for patients beyond that age threshold, the drug provided no survival advantage whatsoever.

The Hidden Cost of Aggressive Treatment

The study reveals troubling patterns in how older patients respond to intensive chemotherapy. Nearly 40% of patients over 70 receiving oxaliplatin stopped treatment early, often because of severe side effects. The drug, known for causing painful and persistent nerve damage, proved particularly harsh for aging bodies.

“The most important point is that oxaliplatin improves survival only in patients with stage III colorectal cancer who are aged 70 years or younger. Beyond 70, the benefit disappears, and oxaliplatin is associated with higher discontinuation rates due to toxicity.”

Dr. Jun Woo Bong from Korea University Guro Hospital, who led the research team, emphasized how these findings could immediately change clinical practice. The study’s methodology was rigorous – researchers systematically tested age thresholds from 60 to 80 years, using advanced statistical techniques to identify the precise point where benefits vanished.

For stage II colorectal cancer patients, the news was equally definitive: oxaliplatin showed no survival benefit at any age. This finding challenges the routine use of intensive chemotherapy regimens in early-stage disease, regardless of patient age.

Rethinking Cancer Care Economics

The implications extend far beyond individual treatment decisions. Healthcare systems spend billions annually on chemotherapy regimens that may provide no benefit to significant patient populations. Dr. Seogsong Jeong, a study co-author, noted the broader significance.

“Clinical practice guidelines may adopt age 70 as a critical factor in recommending oxaliplatin, laying the foundation for precision oncology and future research focused on safer, more effective treatments for older patients.”

The research arrives as cancer increasingly affects aging populations worldwide. Colorectal cancer rates continue climbing among older adults, making treatment optimization critical for both patient outcomes and resource allocation.

Previous studies produced conflicting evidence about oxaliplatin’s effectiveness in elderly patients. The landmark MOSAIC trial suggested limited benefits for patients over 65, while other research claimed survival advantages for those over 70. This Korean analysis, drawing from a complete national database, provides unprecedented clarity.

The study’s size and scope – encompassing virtually all colorectal cancer patients treated in South Korea during the study period – lends exceptional weight to its conclusions. Unlike clinical trials with strict enrollment criteria, this real-world analysis captures the full spectrum of patients oncologists actually treat.

Interestingly, the research highlights how treatment decisions currently vary dramatically by age. Only 9% of patients 70 or younger received non-oxaliplatin regimens, compared to 39% of older patients. This suggests clinicians already recognize age-related treatment limitations, though without clear evidence-based guidelines.

The findings also illuminate the complex relationship between treatment completion and survival. Patients who discontinued chemotherapy early showed significantly worse outcomes across all age groups, emphasizing how treatment tolerability directly impacts effectiveness.

Looking ahead, these results may accelerate development of age-appropriate cancer therapies. Rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches, oncologists could tailor treatments based on biological rather than chronological factors. Future research might focus on identifying biomarkers that better predict treatment response in older adults.

For now, the message appears clear: aggressive chemotherapy regimens designed for younger patients may do more harm than good in those over 70. As cancer treatment increasingly emphasizes precision medicine, age 70 has emerged as a critical dividing line that could guide treatment decisions for years to come.

JAMA Network Open: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.25660

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!