President Joe Biden’s Intelligence Advisory Board now includes a top climate scientist.

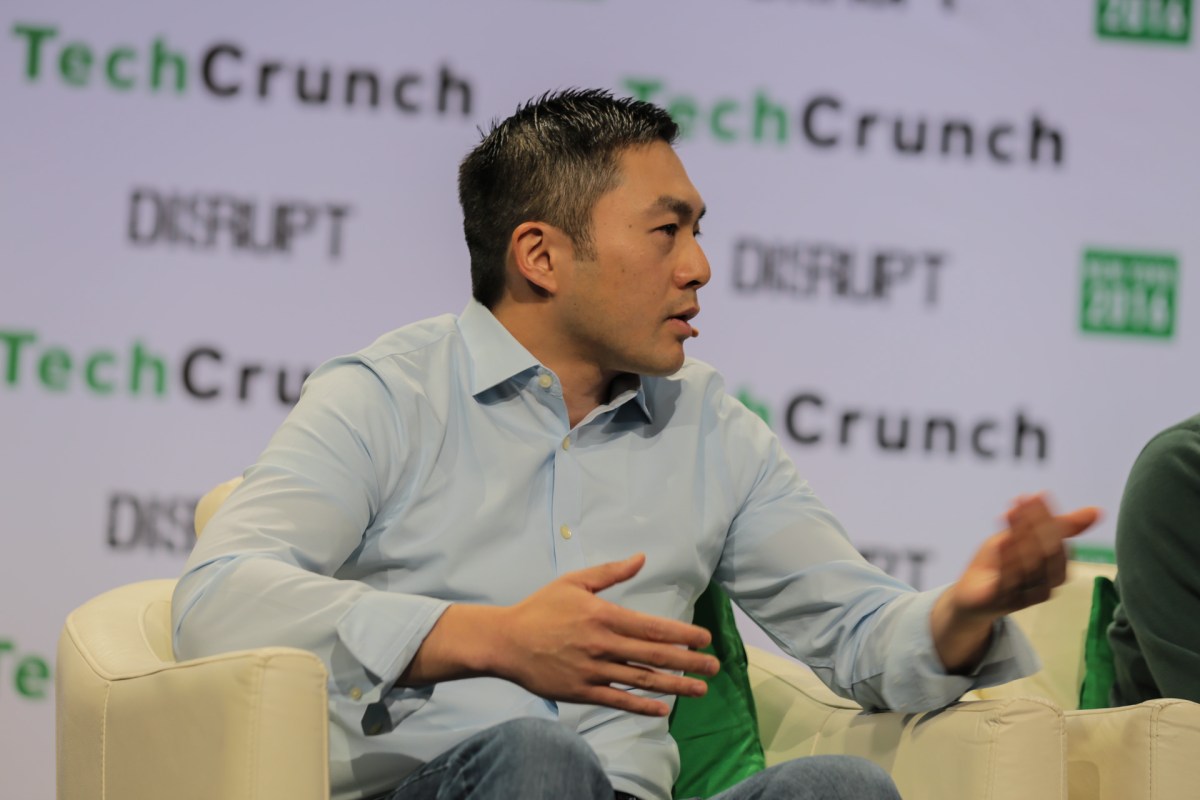

Biden recently announced the appointment of Kim Cobb, an earth sciences professor at Brown University and a lead author of the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, released in 2021, to the White House council that’s tasked with evaluating the effectiveness of the nation’s intelligence community.

The council provides recommendation to the White House, and presidents have both followed and ignored its advice in the seven decades since it was founded. Shortly after taking office in January 2021, Biden issued a series of climate-related executive orders, including one that required the intelligence community to assess the national security threats posed by climate change.

The result was a National Intelligence Estimate that predicted rising geopolitical risks as nations increasingly argue over each others’ failures to reduce greenhouse gases. That could lead countries to harden their borders against high-carbon products and climate migrants. The report also warned that conflicts between nations could rise over water, minerals used in clean energy technology and food.

“The cooperative breakthrough of the Paris Agreement may be short lived as countries struggle to reduce their emissions and blame others for not doing enough,” the report said.

For years, climate science has been an important consideration for the U.S. intelligence community, a sprawling collection of at least 19 agencies including the Director of National Intelligence, the CIA and the Energy Department’s Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence.

“It’s very clear that in order to get the best possible intelligence assessment of security threats around the world, one has to integrate the environment in which those threats are operating and what may influence those threats,” said John Conger, principal deputy undersecretary of Defense in the Obama administration and senior adviser to the Center for Climate and Security. “That includes things like food security, water scarcity, extreme heat, melting of arctic ice caps and different weather patterns that are going to influence people on the ground.”

There are numerous examples of how the effects of climate change in other parts of the world threaten the United States, he said. That includes the movements of Russia and China in the Arctic as sea ice melts, rising tensions over water scarcity in India and Pakistan and heat waves and drought that force migration in South and Central America.

Cobb has a doctorate in oceanography from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. One of her areas of expertise is paleoclimatology, and she has traveled the world tracking climatic changes over centuries using corals and cave stalagmites. She has documented climate change through a 7,000-year period at the Northern Line Islands in the Pacific and discovered that a record-breaking marine heat wave in 2016 killed 90 percent of its reef. She has also found that climate change may be intensifying El Niño events over the past 50 years.

Other members of the Intelligence Advisory Board include: former Homeland Security Secretary Janet A. Napolitano; Richard R. Verma, former ambassador to India and assistant secretary of State; and Chair Admiral James A. “Sandy” Winnefeld, Jr., a U.S. Navy flight squadron commander and former Topgun instructor.

Cobb declined to comment for this story. A White House spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

The Intelligence Advisory Board was established by former President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956 as the Cold War was ramping up.

Eisenhower launched the council to incorporate the work of civilian scientists and engineers in the aftermath of World War II, said Michael Desch, director of the Notre Dame International Security Center and co-author of “Privileged and Confidential: The Secret History of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board.”

It was a recognition that a lot of military-relevant technology, most notably the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb, relied on experts outside of the military, he said. Eisenhower wanted to be sure that expertise helped inform the intelligence community and some of his own decisions.

Desch said he believes this is the first time the panel has included climate scientist.

“It is a fascinating part of the intelligence community and potentially one that, if used correctly, can make a difference,” he said. “And I would say appointing a climate scientist would be an example of thinking about the board the way it’s been used most effectively.”

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2023. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.