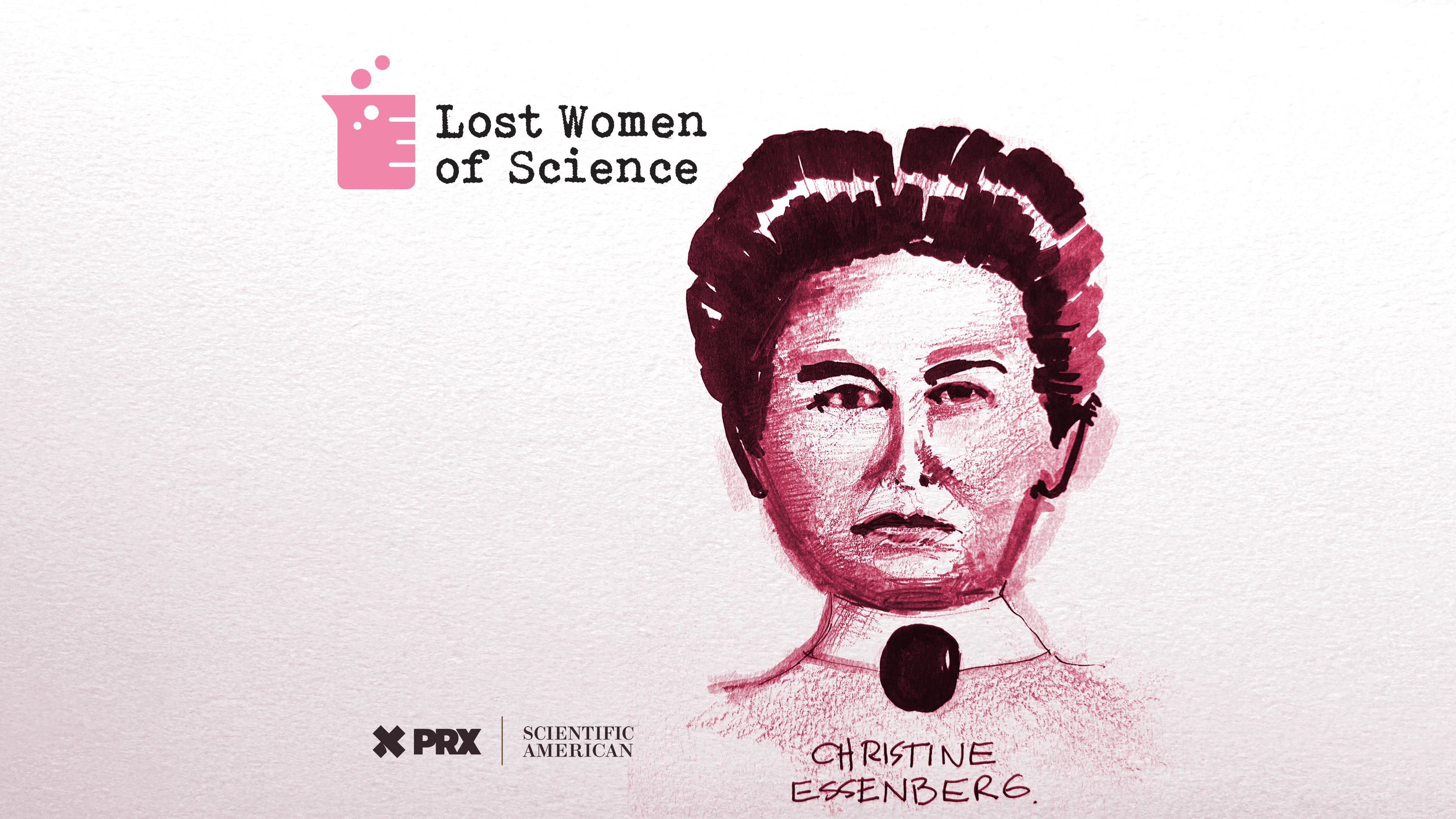

Christine Essenberg had an unusual life and career trajectory. She was married, then divorced and earned her Ph.D. in zoology from the University of California, Berkeley, at age 41. She went on to become one of the early researchers at what is now the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. We know the story of Christine Essenberg only because of a serendipitous find.

While searching in an archive jammed with the papers of male scientists, host Katie Hafner came across a slim folder, called “Folder 29,” in the back of a box at the University of California, San Diego, Library’s Special Collections & Archives. There were just eight pages inside to use as a jumping-off point to flesh out a life, which raises the question: How many other unknown women in science are out there, hidden away in boxes?

This is Christine Essenberg’s journey from researcher to teacher. It’s the first discovery of what we’re calling the Folder 29 Project, a research initiative to uncover the work of lost women of science, hidden in the archives of universities across the country.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

[New to this season of Lost Women of Science? Listen to Episode One here first, then Episode Two, then Episode Three.]

Lost Women of Science is produced for the ear. Where possible, we recommend listening to the audio for the most accurate representation of what was said.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Lynda Claassen: How much there is to be done, and how little one knows. Yours respectfully, Christine Essenberg.

Katie Hafner: That’s the closing line of a letter that zoologist Christine Essenberg sent to her boss a century ago.

I’m Katie Hafner, and this is Lost Women of Science.

A while back, I was poring over papers of a renowned scientist at UC San Diego when suddenly, an accidental discovery. At the very back of a box, there was this. Folder 29. Eight pages of paper. Two letters, written to a Dr. Ritter in 1921 from a Christine Essenberg, and a single letter the following year 1922. There, in fine cursive Essenberg worries about how to help her dying sister back in Switzerland. She considers becoming a school teacher, noting the pay is better. She politely inquires, asking when her research will finally get published. Most intriguing to me: in one letter, she appears to chuck it all and head off to Constantinople.

What? Who? Who was this, and what’s she doing buried in this box? These poignant letters, fragments of a life, survived only because they were part of another scientist’s archival collection. Which makes me think, just how many Folder 29s are there out there in archives just like this?

Folder 29, lost in the back of an archive, haunted me for months. And so I sent producer Claire Trageser back to the UC San Diego archive to dig a little deeper.

Claire Trageser: Hi. Welcome. Are you Lynda?

I’m Claire.

Nice to meet you. Nice to meet you.

Claire Trageser: I made an appointment with Lynda Claassen, the longtime director of Special Collections and Archives. And she has set aside time to delve deeper into Folder 29.

Lynda Claassen: And I only have until 12:25. I’m sorry.

Claire Trageser: She has set a standard cardboard archive box on the table, labeled box five. It contains the collected papers of Carl Eckart, a geophysicist who Katie was looking into a while back. And Katie’s right about this mystery folder.

Lynda Claassen: Eckart. Eckart Ecker. Remind me what we’re looking for. What’s her last name?

Claire Trageser: Essenberg.

Lynda Claassen: Oh, of course it’s the last folder in this box.

Claire Trageser: Linda pulls the folder out and the first thing she notices is the swirling cursive on parchment paper.

Lynda Claassen: How wonderful. These wonderfully polite, nice letters that people used to write on paper in, in nice, neat handwriting

Claire Trageser: It’s a letter dated June 18, 1917 to Christine Essenberg. She has just earned her PhD in Zoology, and is working at what is now Scripps Institution of Oceanography on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in La Jolla, California. She has a passion for research, and is also assisting at the institute’s small library. Lynda Claassen leans in for a closer look.

Lynda Claassen: Let’s see. Thank you for your note. And yeah,

Clair Trageser: Can you read it a little bit or just shall I read it?

Lynda Claasen: Yeah, sure.

Claire Trageser: That’d be great.

The letter is from The Academy of Natural Sciences and gives a sense of the kinds of mundane tasks that she did at the library. It seems that she had flagged a missing periodical. And here is the response written to her, all dry and formal.

Lynda Claassen: My Dear Mrs. Essenberg, I thank you for your note regarding the institution’s subscriptions.

Claire Trageser: And the note goes on to say it was a misunderstanding on the part of the mailing clerk and the error has been corrected. So she was dealing with minutiae, settling up back issues of a journal. It’s a far cry from the field research she craved. At least, that’s our guess. We only have these eight pages of letters to go on. Just eight pages to try to understand the story of a life.

And that’s the point of this project. There are probably so many women like Essenberg, just waiting to be discovered. Each with a unique story, women battling to do their own research in a man’s world.

We only stumbled on Essenberg because Katie happened to find her letters tucked away in the back of a box.

So now our quest is to try to find out as much as we can about Essenberg, with these eight pages as our jumping off point.

This much we know. Christine Essenberg came to San Diego after earning her Master’s and then in 1917 completing her PhD from U-C Berkeley. Her doctoral thesis was a mouthful, titled “The Factors Controlling the Distribution of the Polynoidae on the Pacific Coast” We’ve since come to learn that Polynoidae are scaly worms that live in the ocean.

How did she arrive at this very specific topic?

Well, for one, many of the early scientists like Christine Essenberg, studying at UC Berkeley, were Zoologists.

Professor Joseph LeConte established the department in 1887.

Then zoology was taken over by William Ritter, who eventually went south to San Diego and established the Marine Biological Association, which became Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

And, more importantly, it appears that both LeConte and Ritter took a special interest in mentoring women, and helping them progress in their scientific careers.

Ritter was married to a physician, who may have influenced his views on women, or perhaps he went into the marriage fully formed as a man ahead of his time.

What we do know is that the newlyweds were an adventurous pair. On their honeymoon, they went to a southern point in San Diego to collect goby fish specimens. We know that their boat capsized, and they had to be rescued.

William Ritter was Christine Essenberg’s boss, and the next letter is written by Essenberg to Ritter in May of 1921, four years after she received her PhD.

Archivist Lynda Claassen reads from it.

Lynda Claassen: Have you thought about, or have you found out anything about the publication of my appendices or copelata work?

Claire Trageser: So her research has moved from the scaly worm to the species of plankton . Clearly, the ocean is influencing her. As the letter continues, she’s looking ahead, thinking about the next steps in her career

Lynda Claassen: I would like to do some experimental work on the side, so as not to be obliged to sit at the microscope all the time.

Claire Trageser: Remember, this is 1921. Women had just won the right to vote a year earlier. Very few had careers at all. And so Essenberg was battling not just the idea that she should be working, but that she should be doing the type of work she liked.

In this sobering letter, she’s surprisingly candid with Ritter. It’s clear that she is depending on him both for financial and emotional support.

Lynda Claassen: My sister is sick in Switzerland now. In case she should die, I shall go after her child and raise her.

Katie Hafner: Amazing. right? Yes.

Claire Trageser: Katie has been listening in on her cell, following along as we go through the letters.

What we’re gleaning from them is that this is a woman determined to make her way in the world as a scientist, but with few prospects despite her PhD.

Not to mention a very ill sister, with thousands of miles separating them.

And a boss who likely had more pressing concerns than Essenberg’s troubles. In her letter, she notes her research would take “years and years of patient study.” That would be impossible to set aside once it’s started, making it difficult, she writes, to fulfill obligations, both to herself and to her family. Essenberg then makes a not-so-subtle case for better pay.

Lynda Claassen: I may be obliged to go to teaching where I can earn more in nine month’s work. The beginning salary of grammar school teachers is $1,500. It is only fair that I should expect at least similar salary especially when I am under obligations to help my people. It would be selfish of me to follow my dreams and leave them to suffer and die.

Claire Trageser: It seems Essenberg was treading a thin line with her boss, asserting herself, but not being too assertive.

Lynda Claassen: I am sorry to disturb you with my tales of woe, but you will understand better my attitude and my lack of definitive decision. I hope not to disturb you again in the future. Yours respectfully, Christine Essenberg.

Claire Trageser: By the end of the year, Essenberg is taking a new tack. In December of 1921 she proposes a one-year leave of absence that will take her to research labs across the globe, and — likely not incidentally — within striking distance of her ailing sister in Switzerland. Three months later, in March of 1922, her travel plans are approved. The letter from the President of the University of California is not addressed to her, Dr. Essenberg, but to her boss, Dr. Ritter. It grants “Mrs” Christine Essenberg, a one year leave of absence starting that summer, July of 1922 and ending June of 1923.

Lynda Claassen: Without salary, of course.

Katie Hafner: What, what did you say,

Lynda Claassen: She’s being granted leave, but without salary.

Katie Hafner: Wow. So how did she support herself during this year, I wonder.

Claire Trageser: What we do know is that, about two months into her unpaid leave, Essenberg wrote from the most unexpected of places.

Lynda Claassen: A letter in September of 1922 from Christine to Dr. Ritter.

Katie Hafner: And where’s she writing from?

Lynda Claassen: The Constantinople Women’s College. In Constantinople, Turkey.

Katie Hafner: Wow. How did she get there? How did that happen?

Claire Trageser: Indeed she was teaching at The Constantinople Women’s College. It makes sense. If she stuck with her plan, Dr. Essenberg spent the first two months of her leave traveling to various marine labs. Perhaps she followed through and visited her ailing sister in Switzerland. But remember: It was an unpaid leave. By that fall of 1922 she could very well have exhausted her savings. So teaching, which she earlier noted was more lucrative than her Scripps job, made sense. A teaching position at the Constantinople Women’s College would keep her afloat. And it turned her life in an entirely new direction, one she chose for herself. She picked a heady time to be in Constantinople. On the heels of World War One, there was a lot of instability and she walked right into The Turkish War of Independence. But, given what she writes next, she seems undaunted.

Lynda Claassen: I am not the least bit nervous or afraid. Neither does anybody else here at the college pay much attention to the political affairs. . .until the British officers are leaving Constantinople.

Claire Trageser: Despite the chaos all around her, Essenberg presses on for recognition in her field.

Lynda Claassen: Then she has a paragraph: I hope my paper has gone to print. I sent a brief paper to Mrs. Genter, asking her to hand it over to you. If you find it worthwhile publishing, you will kindly send it to the press.

Claire Trageser: With a war swirling around her, she updates Ritter in September of 1922, writing about how, despite the chaos, her students are still showing up for her class, and she frets about their future.

Lynda Claassen: I feel sorry for them. After they finish their college, they are discontented with their home life. According to their customs and traditions, there was very little of wholesome pleasures left for the Turkish woman. She’s not supposed to do any work either at home nor in public, nor is there any intellectual or social life for her.

Katie Hafner: Oh, wow.

Lynda Claassen: Right. Some of the women — and I think she means all of the women in the college, not just the Turkish women — some of the women are very capable and they are all charming. The education here is making a great influence on the women and will gradually change their position. The change is already noticeable in Constantinople. The girls here suffer a great deal on account of the war rumors and feel as if they had to apologize for some of the actions of their nation.

Claire Trageser: How would we even know of Essenberg’s struggles and triumphs if her letters had not been included in that archival box of papers? Surely there are countless other women like her. To find out about these kinds of lost women, we called MIT where there is another relatively new initiative to recover the lost women. Archivist Thera Webb is working on it.

Thera Webb: I believe it started around 2016 when one of the archivists at that time had been advocating for a focus on collecting the papers of women faculty.

Claire Trageser: She says one of the big challenges in tracking down women is that they are more likely to change their names when they get married, so she relies heavily on their maiden names.

Thera Webb: There will be like, a folder titled Mr. and Mrs. John C. Smith. And then you’re like, oh, okay, well who is Mrs. John C. Smith? And so there’s a lot of research being done by archivists and interns, that’s sort of tied to genealogy in that we’re like tracing back to get to the birth name of these women who are in our collections. There was a folder for Mr. and Mrs. Williams C. Russo. And what I learned was that Mrs. Williams C. Russo was actually Margaret Hutchinson Russo PhD, who was an engineer who designed the first commercial penicillin production plant and was the first woman to become a member of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers. But I never would’ve known that from the name on the folder.

Claire Trageser: But more broadly, it’s a challenge, Webb says, because artifacts from the lives of women in science are typically not as valued.

Thera Webb: Maybe somebody held onto all of the papers of some woman, but they were never accepted by a repository as a collection that people were interested in. So sometimes it is really the case where you can only sort of piece together bits and pieces in collections that belong to men.

Claire Trageser: Webb says the movement to find and archive the papers of women scientists is just gaining steam. There’s more attention to women’s contributions and still a lot out there to be found.

Thera Webb: Whether they’re at a repository right now at a university or a historical society or in someone’s shoebox under their bed, the letters of their great-grandmother who happened to be a scientist, but at this moment, if you don’t know what you’re looking for, you won’t be able to find it. And we don’t know what we’re looking for a hundred percent of the time.

Claire Trageser: MIT is one of several schools plumbing their archives. At UC Berkeley, the search is also on to document the working lives of women who have worked there.

There, Sheila Humphreys, an emeritus engineering professor at UC Berkeley, has thrown herself into the research. She’s very no-nonsense. She wanted to know right away how I’d become interested in the idea of lost women.

It’s kind of like the jumping off point is a couple letters from a woman scientist in San Diego at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Sheila Humphreys: But what was her name?

Claire Trageser: Uh, Christine Essenberg.

Sheila Humphreys: Oh my God, I’ve, I’ve researched her for months. I have a whole essay about her.

Claire Trageser: Oh wow. Okay, great.

What were the odds? What luck! Serendipity had taken me directly to a Christine Essenberg expert!

And she has plenty to say.

Just ahead…

Dominique Janee: Hi. I’m Dominique Janee, an Associate Producer at Lost Women of Science. We don’t know how many Folder 29’s are out there buried in archives around the world. But we’re guessing there are a lot of them. If you’re interested in helping us with our Folder 29 Project, an ambitious dig through archives, looking for lost scientists like Christine Essenberg, go to lostwomenofscience.org to find out more.

Sheila Humphreys: You, you know, she has the most fascinating, strange story.

Claire Trageser: That’s Professor Emeritus Sheila Humphreys of UC Berkeley, talking about Christine Essenberg. Over a century ago, Essenberg was an early research scientist at what is now the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Humphreys told me that she had researched Essenberg, along with many other early female scientists. She wrote a 168 page essay about these women, so I asked her to send it over. Then, with essay in hand, Katie and I started scrolling through the details of Essenberg’s life.

Katie Hafner: This is quite a find.

Claire Trageser: This says she was known for her expertise in plankton, which we kind of…

Katie Hafner: … figured out.

Claire Trageser:. Yes.

Katie Hafner: Right.

Claire Trageser: She’s, born of Swedish parents, which we had sort of had some inkling of, right?

Katie Hafner: Uh-huh.

Claire Trageser: Essenberg had a whole life before coming to the United States. She had been teaching for several years in St. Petersburg in Russia, but once in the U.S. went to Indiana, to Valparaiso University where she studied zoology and botany.

Claire Trageser: And she got married before she graduated, and then later divorced. Interesting.

Katie Hafner: Was the husband Essenberg, or was her maiden name Essenberg?

Claire Trageser: Her maiden name was Adamson, and her husband’s name was Essenberg. She got divorced, but I don’t know if she, maybe she kept Essenberg or, um mm-hmm.

or just the, what? The letters from the time that we had, she was still married. It doesn’t say when she got divorced.

Claire Trageser with Katie Hafner: She’s, oh my God. There’s her picture. Where? She looks so different from what I thought she would look like. Um, and this photo of her is just with the broach and she looks , she looks young, This is amazing.

Claire Trasgeser: The more we pore over in the essay, the more questions we have. So we go right to the source herself: Sheila Humphreys, who had compiled all of this information. But first we had to ask her: What was it about Essenberg that caught your eye? Humphreys had a quick and simple answer.

Sheila Humphreys: The reason that Christine Essenberg came to my attention was that She was 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. She was the sixth woman to get a PhD in Zoology, so she was very, very early, and that’s why she’s one of those women that I profiled.

Claire Trageser: Humphreys explained that, in an effort to rediscover lost women scientists, each department at UC Berkeley was asked to compile a history of women in their disciplines.

Sheila Humphreys: In the case of oceanography in which Christine Essenberg belongs, she was originally a student in the Department of Zoology, which was one of the first departments established at Berkeley. It was taught from the very beginning.

Claire Trageser: So…you’d think there’d be plenty of documentation, but you’d be wrong. The search for Esssenberg was complicated. Departments had consolidated over the years. Humphreys says 23 departments were merged into three, so Zoology, Essenberg’s specialty, essentially disappeared. There was little institutional memory of her.

Sheila Humphreys: And that’s how I personally came to know Christine because I decided to fill the gap that I would take this on.

Claire Trageser: Sheila Humpreys says that, in researching Essenberg, she learned a lot about the early years of Scripps itself.

Back in Essenberg’s day a century ago, the lab was in its infancy and working conditions brought men and women together under very rudimentary conditions.

Sheila Humphreys: They had a temporary lab, they had set up tents and they had one boat and they camped over the summer. And indeed these early women who did their research there, once they went off to teach at various places like Wellesley College, they would come back in the summer to continue their research under Dr. Ritter.

Claire Trageser: And come back they did. The less-than-optimal conditions required the kind of close cooperation that encourages collegiality.

Sheila Humphreys: And I attribute, and I think others do too, some of their success to the fact that it was a very congenial colony of people. And Ritter’s wife Mary Bennett Ritter was the physician to women’s students, but she went down with her husband to help establish this marine biology lab, and she was a trusted maternal presence and advisor and friend to some of these women.

Claire Trageser: Humphreys says the mutual respect that was nurtured helped to break down barriers.

Sheila Humphreys: These women, even though they were probably the single woman in their cohort, they do not talk about feeling discriminated against or that there was any kind of resentment of them at all. It was a very, seems like a pretty happy place where they had Saturday night suppers of clam chowder on the beach and uh, there was even a small school for people who had families, but anyway, that’s how I got to Christine Essenberg.

Claire Trageser: It all sounded pretty idyllic, but Humphreys says it wasn’t always that way. From Essenberg’s letters to Ritter, while men in her cohort are moving ahead, it seems she has stalled out. It was a constant push to get her research published.

So it didn’t seem so far-fetched that she would make good on her veiled threat to take a teaching job for better pay, especially when she saw the war-time need for science teachers at that all women’s college in Constantinople. Opening up the world to her students only to see the walls close in on them later when they left, was something she struggled with.

Sheila Humphreys: She talks about what a prison these girls would be in, especially the Turkish girls. After they finished their education, they were not supposed to do any work outside the home. In fact, they were barely meant to leave the home.

Claire Trageser: And she didn’t worry only about her students.

Sheila Humphreys: There’s reference to her creating a, a program for their mothers to come and do, I think physical education using the school building. Overall she wanted to, to educate them and to liberate them.

Claire Trageser: So it’s clear that teaching at the school in Constantinople was really eye-opening for Christine Essenberg. Still, we do know that she ultimately left the Women’s College there. But Katie, guess where she went next.

Katie Hafner: Back home to the United States?

Claire Trageser: No. Or at least not for long. She went to Damascus, Syria. To start a school of her own. The American School for Girls opened in the fall of 1925.

Katie Hafner: Oh! Damascus! Did she succeed? Did she make a go of it?

Claire Trageser: Yes! Yes, the school was unique. It admitted not just Muslim students, but there were some Jewish students and Christians too, according to Sheila Humphreys.

Sheila Humphreys: This school was very well known at the time, and she had very well known scientists on the board, you know, people from Harvard and all over the place.

Claire Trageser: People like the Harvard Astronomer Harlow Shapley, who served on her board.

Katie Hafner: Harlow Shapley? Oh my gosh! He was featured prominently in an earlier Lost Women of Science episode, the one about Astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. So Payne-Gaposchkin worked for him at Harvard.

Claire Trageser: Yeah, that’s right! And we know that, two decades after its founding, during World War Two, the doors of The American School for Girls stayed open. Even during the bombardment of Damascus in 1945, Christine Essenberg did not leave her post.

Sheila Humphreys: And she stayed there and it was bombed. And her school was sort of a center for expatriates who were stuck there.

Claire Trageser: And not just a center. Humphreys says Christine Essenberg allowed part of her school to be used by the Allied soldiers.

Katie Hafner: Did her school survive the war?

Claire Trageser: We know that the year after the war ended, 1946, Shapley from Harvard was chairman of the board of her school. And we know that in subsequent years, Christine Essenberg made multiple trips back to the United States to drum up financial support for her school.

She appealed for donors coast-to-coast. There’s a local newspaper in New Jersey that talks about one of her fundraising visits, and The San Francisco Examiner noted her stop there to gather support in 1947. By then she was 71 years old. And when questioned about creeping Orientalism, as it was referred to at the time – efforts to teach western values, Christian values – she’s quoted as telling a reporter, “It was never my purpose to endeavor to ‘westernize’ these girls. My primary objective,” she said, “is to educate.”

But Katie. That’s pretty much where the trail grows cold.

We do know she ultimately did return to California at the end of her life. She spent her final years in San Francisco and died in 1965 when she would have been about 89 years old.

Katie Hafner: Well, but, do we know whether she ever did get published? I mean, that seemed to have been a recurring sore spot for her in all the letters she wrote back in the 1920s.

Claire Trageser: Yes, she did. We found at least nine papers from early on. But by the time her last papers were getting published, she was already teaching abroad. Teaching science. To girls and women.

Katie Hafner: So, this much we do know. Christine Essenberg came to the United States. She ended up in California by way of Indiana as an older student, apparently with a marriage and a divorce thrown in. She got her PhD at 41, becoming one of the early researchers at what is now called The Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

But in the end, snippets from her letters tell the story of a female scientist who carved out a niche for herself in the most traditional of all women’s professions: teaching school.

Claire Trageser: So maybe Christine Essenberg became a teacher because she was kept at the microscope and not allowed to do the field research she craved, and so she turned to one of the few occupations open to women back in the day. Or, as Essenberg pointed out to her boss when she was angling for a raise, teachers were simply being paid more than she was being paid, even with her PhD.

Katie Hafner: Or maybe, finding herself in Constantinople with girls and women who didn’t get the education that she herself got, she then got more satisfaction setting up a school for them.

Claire Trageser: And who knows. I mean maybe at some point, when she was teaching, she inspired a girl, or two girls, or a dozen, to shine in science.

Katie Hafner: Yeah. I mean, we’ll never really know. All we know is that she was a creature of her time and made her adjustments and appears to have built a satisfying and adventurous life, because really, all we had to go on as a jumping off point were these letters tucked away in Folder 29.

Well, thank you, Claire.

Claire Trageser: Katie, you are so welcome.

Katie Hafner: Claire Trageser produced this episode of Lost Women of Science. Barbara Howard was Managing Senior Producer with help from Associate Producer Dominique Janee. And we’d like to thank Thera Webb at MIT, Lynda Claassen at UC San Diego, and Sheila Humphreys and Jill Finlayson at UC Berkeley. Our audio engineer is Hansdale Hsu and Lizzie Younan composes our music.

Thanks as always to Amy Scharf and Jeff DelViscio. We are funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Schmidt Futures. Lost Women of Science is distributed by PRX and published in partnership with Scientific American. If you’d like to help us bring lost women to light through our “Folder 29 Project”, and we hope you will, go to our website, Lost Women of Science dot org. I’m Katie Hafner, thanks for listening.

—

Further reading/listening

- Early Berkeley Women Doctoral Graduates, Sheila M. Humphreys. (Courtesy Sheila M. Humphreys, EECS Emerita Director of Diversity, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California at Berkeley)

- The Biological Colony, Explorations, Volume 7, No 1. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 2003.

- Folder 29, eight letters from Christine Essenberg, (Courtesy: Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego)

Episode Guests