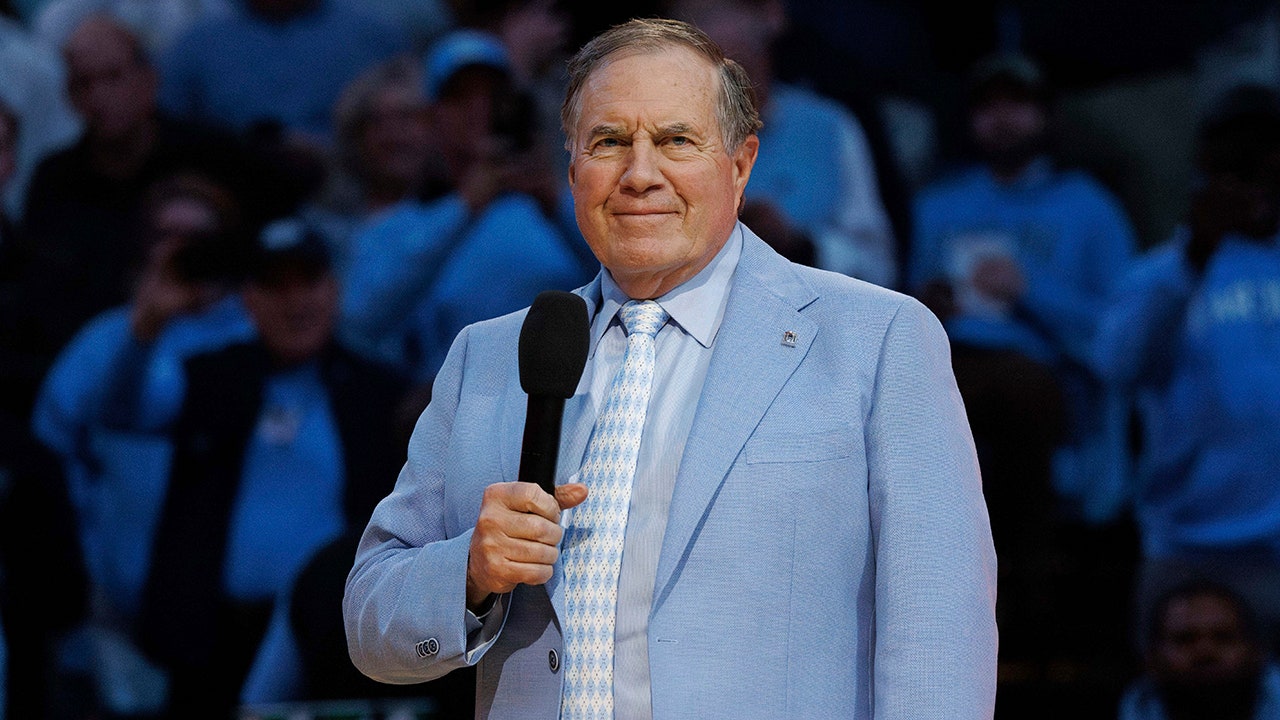

The Pitch: In a near-future world where pollution and technological advancement have led human beings to develop “Accelerated Evolution Syndrome” (i.e. the spontaneous development of new organs and bodily configurations), bodily modifications are the norm and pain is virtually a thing of the past. Save, it seems, for Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen), a celebrity performance artist whose gimmick is tattooing, then surgically (and publicly) removing, the new organs his body generates in elaborate showcases with his creative partner/probably-lover Caprise (Léa Seydoux).

He lives a life of constant pain, one which no number of bio-technological devices — floating orchid-like beds that attach fleshy tentacles to his limbs, living high chairs that rock him as he eats breakfast so he can keep his food down — can suitably alleviate. Yet it’s that pain, and the desire to excise it from his body, that makes him the best, a true artist in a world of faux-edgy poseurs who bold fake ears onto themselves to reach for the same notoriety.

It also attracts no number of other interested parties, from a pair of bureaucrats at the newly minted National Organ Registry (Don McKellar’s Whippet and Kristen Stewart’s frazzled fangirl Timlin) to a detective (Welket Bungué) who uses him as a stool pigeon for illegal body modders. And it might lead Saul to his most ambitious show yet, as a grieving father and activist (Scott Speedman) urges him to perform his next public autopsy on a dead body — his son’s — promising Earth-shattering revelations for his audience.

Long Live the New Flesh, Same As The Old Flesh: It’d be the understatement of a lifetime to say that horror legend David Cronenberg is no stranger to cinematic body horror: With films like Scanners, Crash, Videodrome, The Fly, and others, the Canadian auteur practically wrote the fleshy rulebook on the genre. His films are dreamlike, meandering ruminations on the blurred lines between human, animal, and technology, testing the limits of what our blood-and-pus-filled meat cages are capable of (and what they might be ready for in the future).

Crimes of the Future is no different, a welcome return to the filmmaker’s body-bending concerns that evokes his prior meditations on the flesh — even as it scrambles a bit to find something new to say that he hasn’t already before.