Zoological Advice for Grieving Daughters

Home Range by Ramona Ausubel

“The Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi), which once ranged throughout the southeastern United States, is now restricted to a small breeding population in southwest Florida south of the Caloosahatchee River. First listed as endangered in 1967 under the original Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 and subsequently receiving Federal protection under the passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the Florida panther was and still remains one of the most critically imperiled large mammals in the world. Although males have been observed at various locations throughout the state, until recent years females apparently did not cross the Caloosahatchee River and no panther reproduction had been documented north of the river since 1973. In the mid-1990s the subspecies was near extinction with around 30 individuals remaining and severe genetic defects due to small population size.”

FROM: “Location and Extent of Unoccupied Panther (Puma concolor coryi) Habitat in Florida: Opportunities for Recovery”

BY: Robert A. Frakes and Marilyn L. Knight

PUBLISHED IN: Global Ecology and Conservation 26 (April 2021)

We are moving into your house, which you do not occupy now because you are dead. Mothers should not die. You were the universe for me, and then you were a planet and now I am supposed to believe that you do not exist.

I can’t talk about this with my children because I would be reminding them, or telling them for the first time, that I will die someday. Instead, I give them each a little plastic Florida panther figurine and a book about the beasts and tell them that we are moving to panther country. I show them pictures of the blonde beasts and their enormous paws, their white muzzle, black rimmed eyes. “There are only a hundred or two in the whole world,” I say, and my daughter nods gravely. She had gotten binoculars for her last birthday. This, age seven, would be her best year yet. My son looks worried. “Panthers are not dangerous?” I tell him that they stay away from people, that they roam the jungle and freshwater swamps looking for rabbits and armadillo to eat. “Don’t think of them as predators, think of them as magicians.” He is nine, which is old enough to understand a lot about the rules of the world, and to feel discomfort with the vast unknown.

My daughter, upon the news, begins a study of the Florida panther. She says, “The species used to live all over the southwestern United States and now there is only one population in southwestern Florida. In the 1970s there were only twenty breeding pairs, but now there are around two-hundred and thirty.” She is seven years old and she seems forty. She taught herself to read at five with the fervor of someone who needed to know the survival manual.

“That’s good,” I say. “They’re doing better.”

She says, “They sometimes kill and eat small alligators and panthers are the leading cause of death for white-tailed deer in the region.” She smiles wide at this because it means the cats are eating.

We are moving into your house because I can’t get a job. The last academic interview I had was in a desert city and I flew in with my suit skirt and my pressed shirt. For two days I told person after person how prepared I was, how ready to teach their students to write essays. I didn’t eat at meals because I was afraid of getting lettuce in my teeth and in the bathroom between talks and meetings I devoured granola bars and willed myself not to throw up. I tried to picture us there. To picture taking the wet, warm storm cloud of our family to that dry place. My husband was excited about it—he imagined desert wildflowers while I’m always simultaneously pulling away from and missing melaleuca, cypress, swamps. When the chair of the search committee called to say that they had chosen the other candidate I told her I understood but that I was now going to have to move into my dead mother’s house. She was silent on the end of the line. That fury is still a flavor I can recall immediately. It’s in my body somewhere, a stalactite in the cave, water beading off drop by drop, leaving the thinnest coat of mineral behind. Mineral that gathers and gathers and gathers until it becomes a dagger.

When I had a mother I wanted no mothering, I wanted to drift in total randomness through space and time as if I arrived here on the back of a comet.

I’m telling you all these things because you are not alive to see them. When I had a mother I wanted no mothering, I wanted to drift in total randomness through space and time as if I arrived here on the back of a comet. I wanted to be a particle or an atom in vastness. Too bad I was landbound, feet attached to the dumb earth, body full of needs. I worked on a fishing boat in Santa Barbara, served biscuits and gravy in Corvallis, and in Santa Rosa I bent staves of oak into barrels in which wine might age. I stayed as far from Florida as I could, because you were there and I was the not-you. Even when I had a family, we kept our distance. Then you got sick and we moved closer. Now you’re dead and we are moving to the very spot you left.

I sit on the small balcony of our Tampa apartment and drink a glass of water. It is hot and I have so much more packing ahead of me. The children have left their plastic panthers on the ground. I google the species. “Young males wander freely but females are reluctant to cross roads or the Caloosahatchee River, which makes them poor colonizers of new territory.”

For six weeks—or, a space of time as long as the universe?—I have been surrounded by objects that feel like they are trying to devour me. I am engulfed by things you paid for, things you took in. Strays. Every pen, every sock, every piece of paper documenting a doctor’s visit, an electric bill. Then I go home and am engulfed by our own menagerie: every piece of art created by one of my children at a gorgeous, singular moment in their lives. This gauntlet of art is one of the most excruciating parts of moving. How many must be recycled. Every time I think of their fat little hands, clutching a marker with intense focus, and here I am, eliminating that work from the world. Sending it to the mulcher. Motherhood is a train of monstrosity. We should be knighted for the things we are asked to kill. I am not in a ring with gold armor, a spear, and a lion. This is much harder: I am in a ring with my mother and a thousand versions of two tiny humans it is my job to love, and I must reduce the miracle down to something I can pack in a finite, practical number of cardboard boxes. The treasures are more dangerous than any wild beast: they eat their prey from the inside.

The boy is a minimalist. He wants puzzles solved, spaces clear, room only for books and important mementos. He keeps a marine protozoa, a white ghost of an ancient creature, suspended in acrylic. He keeps a toy Ferrari purchased in Italy. He keeps the knitted fox I made for him when he was tiny, little red pants, fishermen’s sweater. Maybe this is saved because I am nostalgic, or maybe he cares about it too. Attachment is a habit we practice, our species. To love things makes little practical sense for survival. We are weighed down. We are bound to places that sink or burn or get twisted into the sky by swirls of wind. He will float freely, sail above us in an airship while the rest of us stand with arms full of metal and wood and plastic and jewels.

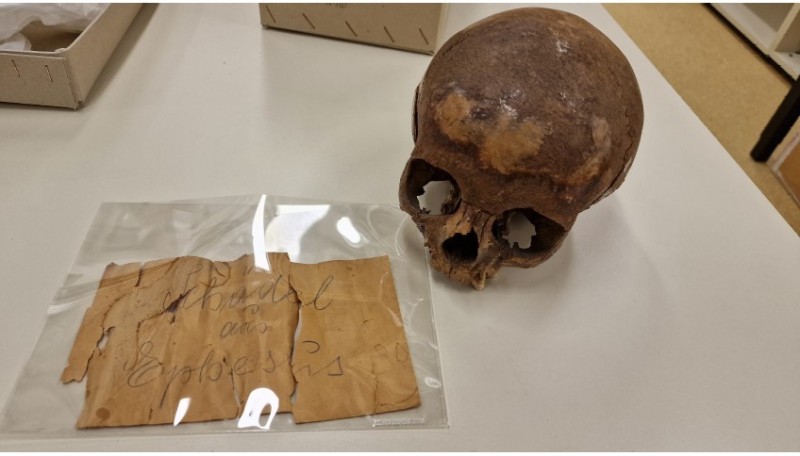

My daughter collects teeth. She has her own, each wrapped in a piece of tissue paper and gathered in a ceramic bowl. You’d never know what they were. Trash, or part of an art project, a candy bowl belonging to a witch. If ever she is in a rock shop she buys the tooth of a shark, and she scans the path for them, as if animals are always losing these pearls. It is only one of the things she collects. She throws away nothing she makes so her closet is an archive of cut construction paper, attempts to draw mice in the manner taught to her by a substitute art teacher, evidence of the phase where she drew pictures of her family as figures with only a head and legs. She has nubs of chalk too small to hold. She has been alive for only seven years, seven rotations of the earth, and the contents of that life is all here, the small apartment bedroom a museum of this tiny existence.

Last night, while I tucked her into bed in her nearly bare room, she said to me, “I learned that if you encounter a panther you should make eye contact but not run, which triggers their chase instinct. Panthers usually avoid a confrontation.” I asked if it was like bears, where you put your jacket above your head to make yourself seem bigger. “The book didn’t say. It just said not to ever turn your back.”

“That’s good to know, sweetheart. Thank you for the excellent research.”

“It also said that panther kittens stay with their mom until they are two years old when they go off to hunt on their own. If I were a panther I would already be an adult.”

“Let’s stick together a little longer, okay? For me?”

I am sitting on a box in a living room I will not occupy much longer and I am holding the blue sweater of yours and I am asking for you, the ghost of you, who has not yet visited me, not in the wailing anguish or the bottomed-out sad or the bright peak of memory, to come now and advise about a pile of junk.

I am a cave of collected oddities, things gathered for someone I always thought I was running away from. I meant to leave you but all along I made choices based on your loves, your desires, your urgencies. Everywhere I went, you were an opposing force. What I didn’t know is that you were not against me, that opposite my floating ship, you were my anchor; opposite my suspension bridge, you were the bearing. Now it is time to merge, my life in your home, the saw palmetto, wax myrtle, and Spanish bayonet you planted. Paths through sand, alligators that will outlast us both.

We have woken on this day, and the magnolia tree outside the apartment has flower buds that look ready to break with blossom. Or maybe I am the one who is ready. We are moving out of this apartment where our family has lived for two years. We say that word “lived” like it’s a passive event, but what I mean is that we were sick here, feverish on the couch under a blanket; my husband and I had sex dozens of times in the bed that sits on the floor in the upstairs room; my daughter tucked stuffed animals in under a silk scarf she took from my sock drawer; my son stacked books on astrophysics under books on baking under novels about girls who can turn into dragons; we made and ate the meals that kept our bodies alive for some seven hundred days; we washed the same dishes in the same sink again and again. Is it reasonable for moving to prompt a sense of death? Or maybe it’s this: you came here, to this Tampa apartment. You slept in it. You washed your face here, dried your skin on the towels we still have, now boxed for transport. I can picture you here. Your existence, in this way, is continuous. You will never have been in our new life, but we will inhabit yours. Will I become you? Will your ghost turn the taps on in the middle of the night to torment us? Will you fill our shoes with shredded paper? Or maybe you will be a benign ghost and leave gifts of flower petals, the coffee maker already filled.

On moving day, on the drive south, the children fight about the lyrics to a song on the radio. I turn the song off, which makes them angry at me instead, which was the point. I would rather be the direct recipient of fury than to live in a fog of bickering. “Tell me something you’re excited for in the new house,” I say.

“A bigger room,” the boy says.

“Panthers, obviously,” the girl adds. “There is plenty of suitable habitat in Florida for the panther. The challenge is getting the females to move into new territory.”

The challenge is getting the females to move into new territory.

“Moving is hard,” my husband says. “Even for dads.”

She counters, “Male panthers wander over large areas but females stay close to their mother’s home range.”

I squeeze my eyes tight and then open them wide. I do not want to cry right now. “Having a bigger house will be good for us,” I say. My children are like goldfish that have been kept small by their bowl and now they need to grow, grow, grow. I have a second of panic that they will shoot upward so fast I won’t be able to look them in the eye anymore.

My husband says, “I’m excited to never write a rent check ever again.”

We pull up to the pinkish brown bungalow and I remember being a kid and seeing you out in the yard standing, just standing. It scared me because I did not know why you were so still. You were doing nothing useful, as far I could tell. Not trimming dead branches from the avocado tree, not weeding, not gathering the loose toys. Now I believe that you were hanging onto yourself like a person trying not to get blown off the top of a train. Responsibility must have been moving a hundred miles an hour beneath you. Dad had left. It was always me, needing tape to put up a picture of a horse torn from a calendar; me, needing to know if we were out of cinnamon; me, needing my hair brushed; me and me and me again. The house, too, was always hungry. New lightbulbs, a dripping shower, sticky spot on the kitchen floor, a front door that blew open, sprinkler head broken by winter snow. Your body was useful to us, the house and me, for so many things. I never wondered what you’d do with it otherwise.

We step out of the car, walk the concrete path to the front door, the four of us. The first time we will come here in this way. Home, even though it isn’t yet. I take the keys from my husband who had them because he was driving. It has to be me that lets us in. It has to be me that crosses the threshold first. Are you watching us? I wonder. Are you hovering above, overjoyed, or jealous? If you were alive you would have a jar of lemonade sweating on the table and a gift in the children’s room. Instead, the place will be empty. All sustenance and comfort ours to invent.

The door opens to the pale wood floors, a view of green, green, green yard through the sliders, which are open. And there, in the center of the room, lying on its side, is a cat. A big cat.

“Panther?” my daughter says. “Panther. Panther.” Her voice is shaking.

“Okay,” my husband says. My son is behind me, pulling me back out. The panther has a bird in her mouth. She looks at us but does not seem threatened. We all back away slowly.

Our eyes meet. Hers are a shade of yellow-black. She sees me, through me. Her body moves with breath and there is a low, nearly inaudible rumble. My voice knows it before I do. “Hi, Mom,” I say out loud. The boy pulls me harder. The girl raises her binoculars to her eyes. My husband looks at me and then at the cat. He tugs my hand but I do not follow him back out the front door. The children do. I step forward and kneel down. I put my hands to my heart. “I like your bird.” You curl your front paws. They are huge, and I can almost feel the weight of them draped over me. “We’re here to live in the house now,” I say to the animal, to you. “You can stay around if you want. You are part of why we’re here.”

My husband beckons. “Honey, sweetie. Please come out.” My son is crying. I remember that I am supposed to make eye contact and not back away.

Your muzzle is faintly bloody, I notice. There are feathers on the floor. You stretch and stand, drop your prey. My heart is beating so fast I can’t hear anything else. This is the day I get eaten by an endangered predator.

This is the day I lose my mind. But the cat gives me a look, long and sure, and then turns, her long gorgeous tail sweeping across the floor, and she walks out through the back door.

I hear my daughter in my head, “Male panthers wander over large areas but females stay close to their mother’s home range.”

A big cat walks away through the grass, which is long from a week of late afternoon rain. A woman stands in her mother’s empty house. A woman stands in her own house. The cat is a Florida panther. Or the panther is the woman’s mother. The bird is a pile of blood and feathers. Or the bird is an offering. The woman is the mother. She is in her mother’s home range. She is in her own home range. She is home.