You Can’t Come Back If Your Memories Are Missing

Accidental Girls by Chloe N. Clark

When I see Halley in a bar, years and years past when she disappeared, I know it’s her so quickly and completely that it makes me gasp. The Halley of her thirties is leaner than her teenage self, her hair dyed a blue so dark that in the shady bar I think it’s black, and she has a scar across one cheek. But she still has eyes the color of rainy days, a slight limp on her left side. I wonder if she also has a face etched with living, laugh lines around her eyes, a frown line permanently drawn across her forehead.

“Halley?” I half-shout across the bar. But she doesn’t even flinch or turn. I move through the other bar patrons as quickly as I can, trying not to lose her in the crowd. When I catch up to her she’s talking to a man in jeans and a band shirt of some musician I’ve never heard of. I reach out and tap her shoulder.

She flinches. The man stares at me and she turns. We haven’t been face-to-face since we were sixteen, sitting in my front yard, drinking lemonade in paper cups, talking about what senior year would be like. That was the day before she went missing. The day before everything slipped and crashed. “Do I know you?” she asks.

“It’s Abby?” For a second I feel like maybe I’m the one in the wrong. That she’s still Halley but I’m someone else.

She shakes her head. “I’m sorry? I don’t think I know you?” “From school? Lincoln. We were friends.” Friends feels incomplete.

She half-smiles. “I really don’t think I know you. I’m not sure what Lincoln is. I get confused for others all the time.”

“You’re not Halley Blackwell?”

She shakes her head. But her face is Halley’s face, and her head shake, always so confident and yet so disappointed to be saying no,

is Halley’s head shake. “Sorry. I’m Faye.”

I take a step back. “Sorry. I’m so sorry.”

I retreat back to my corner of the bar. Occasionally, I glance over at her talking with the man. She sometimes laughs, but she never looks my way.

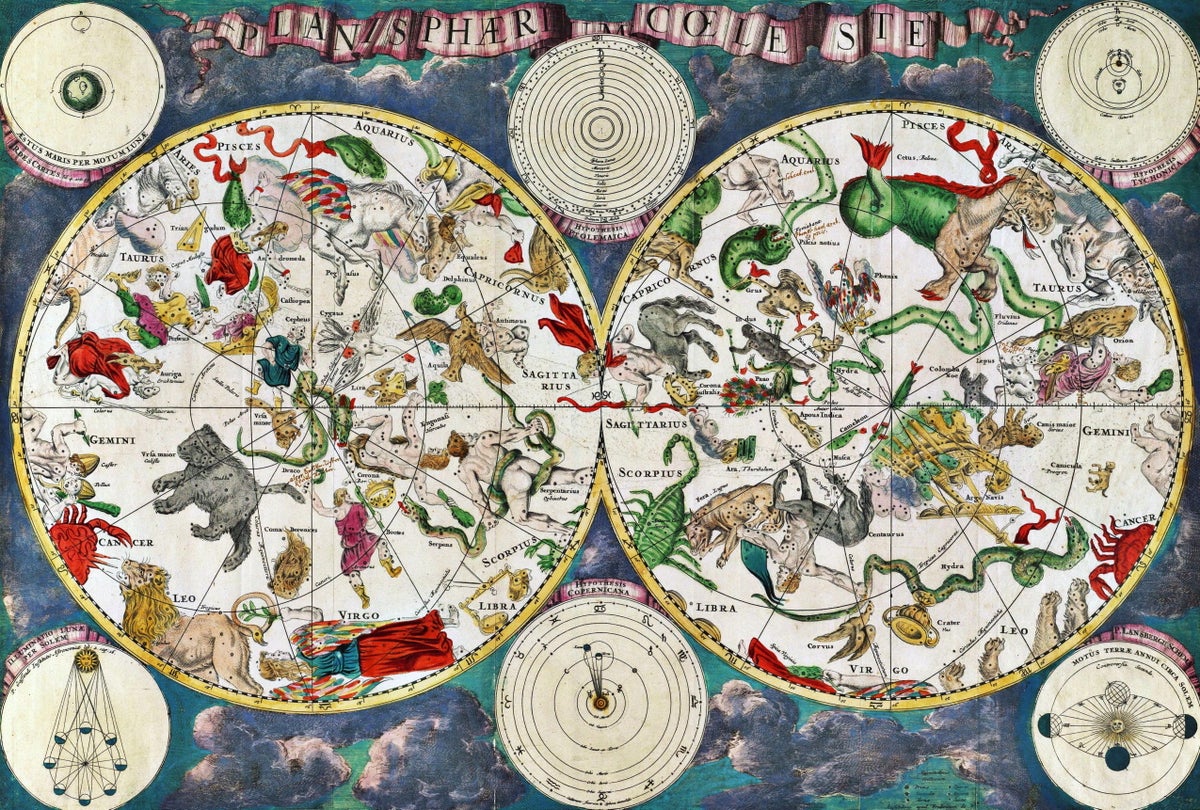

In the dark, at home, I count stars on the ceiling. In my childhood bedroom, I’d put up thousands of them. Every night, I’d find patterns in the way I’d arranged them. Count out in concentric circles until my eyes closed. Even years later, with a blank ceiling, I could still picture where they had all been. When I was young, I’d spent hours making up constellations with Halley during sleepovers. We’d use myths we knew or sometimes our own stories that we’d spool out like threads of our imagination. In Halley’s stories, girls were always lost, turned into lights, into flickers in the dark. I can still trace them all with my fingers.

We were sixteen when Halley disappeared. She was walking home from a football game. We were playing the Wildcats, our town’s rival. Everyone was at the game. If I hadn’t gone with my parents, if my little brother hadn’t been playing, if we hadn’t been waiting to take him out for ice cream after the game, if I’d asked her to join us and she’d said yes, if, if, if, I’d have been walking home with Halley. Her parents don’t call to check if she’s with me. No one reports her missing until well into the next day when I go over to her house to ask if she wants to come over for dinner. Her parents say she sometimes doesn’t come home at night. That it’s normal. They shrug at my insistence that she should be home. But my parents call the police when I tell them. They say it’s better to be safe.

No one finds Halley Blackwell. It’s like she stepped away from the stadium bleachers and right into another universe. There is no evidence. Just an Amber Alert with a picture of her that I took, because her parents don’t have any of her, and her school photo makes her look older than she is. A police officer tells me that a photo where she looks girlish would be best. People want to save girls, he says. I don’t say, Don’t people want to save everyone? I wish I had.

And years pass. And years pass. In college, I imagine that she went to another school and that’s why I never see her. I call her phone number sometimes, but no one ever picks up. And years pass. And years pass.

When I no longer think about Halley every day, when I no longer long to reach her, I still sometimes have nightmares that she is trapped underground. That some devil pulled her under the dirt. She calls out for me to help her, but in the dreams I’m always locked into my seat on the bleachers, I can’t hear her over everyone cheering. If I can find her in the dream, it will undo the past. If I wake up, she‘ll be fine. If I call her, she’ll pick up. If, if, if.

It’s a week before I see Faye again. I hadn’t thought about the interaction much. Usually, just before sleep, I’d see her face and try to find what I thought had been Halley’s features. But memory rearranges us, and I couldn’t be certain I was sure.

I’m grabbing a coffee before work and she’s in the café I always go to. I don’t notice her, but as I’m about to leave, she says, “You’re the woman who I thought I was someone else.”

I turn to her and it’s still Halley’s face. Her blue hair is pulled back into a bun, dressed professionally in tailored pants and a long-sleeved silk blouse draped so lightly on her it looks like the wind would turn it to shreds. I blush, feeling foolish. “Yeah, sorry about that. You really look like a friend I used to have.”

“Scientists say that everyone is likely to have at least one doppelganger,” she says.

I laugh, a little baffled. “Do scientists say that?”

She nods. “Something to do with a limited number of genes to compose humans. There are only so many facial characteristics to go around.”

“Huh. Well, you’re certainly my friend’s doppelganger then.” I move to leave.

“Would you like to get something to eat sometime?” she asks. “I’d love to know more about my lookalike.”

I’m about to say no, to leave, not wanting to carry my mistake forward. But she smiles fully and I can see that her lower canine is cracked off. When we were twelve and playing baseball, a ball hit Halley square in the face. She’d smiled over at me, said, “I’m okay!” but blood had pooled down her face as soon as she spoke. She’d broken her lower left canine clean in half. So, to Faye, I say, “That would be great!”

I write my number down for her and she says she’ll message me to set something up. When I get to my office, my hands are shaking. We’d met in first grade, the two girls in the back row of the classroom. She had a stuffed monkey with her. Benjamin was his name. I like monkeys too, I said, and she smiled. Back then, she was the shy one and I spoke too much. In our teens, we switched. I was all gangly limbs and awkwardness, and she was petite and precise and perfect.

At the office, my first client of the day is new. She runs a business consultation company. I wonder what a business consultation business does exactly, but I don’t ask because I’m supposed to know those things, to understand how businesses operate. I tell her how our services work. Why her business should use one of our training sessions.

The woman frowns more and more as I speak. Finally she asks, “How do you guarantee that what you do works?”

“The answer is we don’t, ma’am. We can’t. I could point out studies we’ve done and how we’ve seen employee charitable donations go up after a training session. I could show you surveys we’ve done several months after the training where employees have listed off positive things they’ve done since. I remember one man who started volunteering at a children’s foundation, and he talked about how much of a change he was bringing to those kids’ lives. I can’t tell you that our services made people more empathetic. No one can tell you that. Results for us are seeing positive changes, but . . . maybe that’s not what you would consider working.” I shrug. I’ve given this speech a thousand times, seen a thousand business owners have a moment’s mental struggle over how they could react. No one wants to say charity isn’t change.

She purses her lips, looks down at the floor, and then back up at me. “Positive results are certainly a huge thing. We would love to have your company come in and do a training if that is the impact.”

I smile my biggest smile. The one I used to practice in front of the mirror. Genuine without being too much, too happy. “You really are working to bring light to this world, ma’am. We’re so excited to partner with your company.”

She smiles at that. We go over the paperwork quickly. Once they’d heard the speech, most people didn’t have many questions. As she’s leaving, she turns back to me and says, “What got you into this line of work?”

The more like us an AI looked or sounded, the more we cared about it, the more we were willing to give it our information, let it into our lives.

I don’t know how to answer. My bosses had seen me give a presentation during college on how advancing robotics could be done not by advancing the technology but by advancing the amount of empathy people had for the robots themselves. The more like us an AI looked or sounded, the more we cared about it, the more we were willing to give it our information, let it into our lives. People would come up to me after and ask if I was looking for work after school. We train empathy, they’d said, and I’d laughed. I figured a friend was pranking me. But I’d looked up the company that night, and when I had graduated and was looking for work, I’d messaged them. I figured I’d be there for a year while I found something I actually cared about. And the years passed, until I couldn’t imagine sending out resumés, writing cover letters.

“I suppose I wanted to help,” I say to the woman. She nods, as if that is enough.

I call my brother at my lunch break. He’s at work but he picks up. “Slow day?”

“I literally watched paint dry earlier. They’re redoing one of the office wings,” he replies. “What about you? You sound like you, but not.”

I wonder what’s in a voice that he could tell. “I think I ran into Halley.”

There’s a pause. Silence. Maybe he doesn’t remember her, doesn’t know who I’m talking about. “Missing Halley?”

“Yeah. Halley who went missing.”

“You think you saw her?”

“This woman looks exactly like her, sounds like her, down to her broken tooth.”

“Okay, did you ask her?” I don’t need to see my brother to know that he has begun running a finger down the side of his desk, a thing he always did when he was thinking through something. After Halley went missing, he’d come to sit in my bedroom, crosslegged on the floor, and it always made me see him again like when he was a little, little kid. He’d never say much, just sit by me, as I stared out the window, trying to will Halley back home.

“She said her name was Faye.”

“Okay, so maybe she didn’t want to be remembered? I always kind of wondered if she’d run away.”

He’d mentioned that once before, had pointed out how we always saw bruises on her, how her parents looked through her when we saw them together anywhere. And I’d wanted it to be true. That she’d simply left, become someone else in a happier place. But I’d thought she’d have said something to me, she’d have reached out, she’d have let me know everything was going to be all right.

“I . . . had that thought. But she really looked like she didn’t know me. And she asked to get dinner, said she wanted to know more about her lookalike.”

A long pause. “I don’t like that. You shouldn’t meet up with her.”

I took in a breath about to explain why I needed to, why it was important, but he cut me off. “But I know you will. Just be on guard, Abs. Sometimes the people we remember should just be remembered.”

Later, when my phone goes off, I think about not looking. As if not giving into temptation is an option. As if I haven’t been scrolling through photos of Halley, looking for other clues I’ll be able to spot in Faye. “Late dinner? — Faye.”

I type back sure. A few moments later my phone lights up again. “I’m new to town. Suggest a place?”

I give the name of a restaurant that’s a ten-minute drive. Far enough to be away from my home, but not so far as to be unfamiliar. I want to be on my own turf. She wants to meet in a couple of hours.

It’s only as I’m changing, slipping out of business clothes into jeans and a t-shirt, that I realize the restaurant I picked is a Greek one. Halley’s favorite food had always been gyros. We’d get them at a local diner and she’d eat them as if she was starving, picking at the meat with her fingertips, grinning. I was never a voracious eater, picking at salads, sipping water, but her joy for food was infectious. She’d say, you have to enjoy things, you have to let them fill you up. When she went missing, I think about all the things she enjoys. All the things she won’t have. And then I push that away. She’s not dead. She has to be alive. She still can enjoy things. If she ran away, if she hopped on a bus out of town, if she’s living somewhere with a house and kids and a life that made her happy. If she never let me know, if she doesn’t trust me to tell me, if I’d never know, at least she was okay. If, if, if.

She’s already waiting for me when I arrive, sitting in a back booth, and staring out the window. It’s dark out, but the sidewalks are well lit and I wonder what she’s looking for. I sit down across from her and she jumps a little, pushed out of whatever thought she’d been in the middle of.

“Hey,” she says. “I was just thinking about how people walking past windows must never think about what they look like to the people inside. Like not knowing what stories we might be daydreaming them into.”

Halley had always known when I was wondering what she was thinking. She’d tell me before I even had the chance to ask.

“I think about people inside like that when I’m walking past. How I’m catching glimpses of them without knowing what they’re thinking, what they’re talking about.” We both turn to look at a couple walking past. They are holding hands but not talking to one another.

“What do you like here?” Faye asks. She picks up the menu and begins glancing at it.

“Oh, I’ve tried a lot of stuff. It’s all good.”

She laughs. “Sounds like you’re talking about life.”

The waiter approaches before I can respond. I see her waiting to see what I’d order.

“A Greek salad and water please.”

The waiter turns to her. “You, miss?”

She glances at the menu one more time. “I’ll do the same. But a Coke instead of water. Thanks.”

I want to say that she should try the gyro, but the moment is gone. She studies me and so I study her back. She’s wearing different clothes—but equally expensive-looking—a long-sleeved and cowl-necked dress also made of silk. A simple gold watch. She looks as if she’s come from a business dinner.

“What was your friend’s name again? The one I look like?”

“Halley. Halley Blackwell.” I say, but there’s no hint of change in her expression when she hears it. It’s someone else’s memory.

“It’s a nice name. Wish it were mine.” She chuckles. “You knew each other when you were teens?”

“Yeah.”

“But not since?”

“No.”

She smiles, just a little, just at the corners of her mouth. More wistful than happy. “It’s a shame that we lose the people we were friends with when we were young.” I nod.

“She must have been a good friend,” she continues. “You looked so startled, but happy, ecstatic really, when you touched my shoulder. I wanted to be your friend then. Wished I was her. So I could continue that happiness.”

“She was a very good friend,” I say. “The best I ever had.”

Our salads and drinks arrive, cutting the conversation. I want to thank the waiter profusely. The conversation felt like a trap, like standing at the edge of a chasm as someone tries to get you to walk closer to falling.

The conversation felt like a trap, like standing at the edge of a chasm as someone tries to get you to walk closer to falling.

We both begin to eat. I pick at my salad, lifting up a single leaf to nibble at. Across the table, she does the same. It’s like she is mirroring what I’m doing. I set my fork down and she does too.

“I noticed you broke your tooth. How did that happen?” I want to catch her off-guard, no time to make something up.

“Car accident,” she replies. “Those air bags are menaces. Did you know they can hit hard enough to take an eye out?”

“I didn’t know that. Wow.”

She nods and her face looks older for a moment. Layers of makeup. Maybe she’s much older than me. Older than Halley. Maybe this is all a mistake.

“What do you do?” I ask. Ready to just make conversation and be done with this.

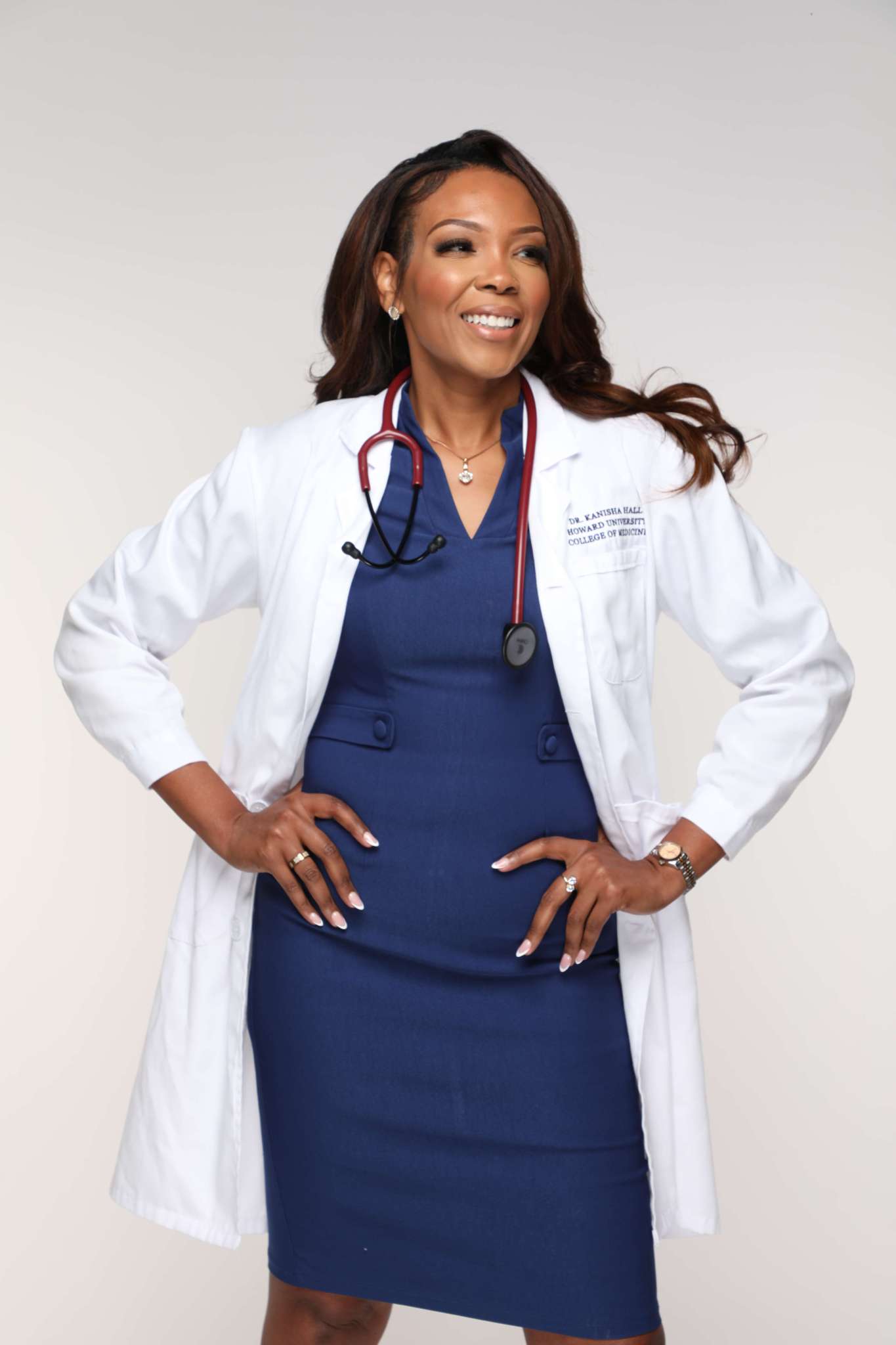

She looks up from her food. “I’m a trauma specialist.”

“Like a surgeon?”

She laughs, and with it she changes completely. It’s a full-bodied laugh that shakes her shoulders. And I am seeing Halley laughing, almost falling off my bed because she’d remembered something stupid a boy had done in class. In the memory, I reach out to catch her. Do I catch her?

“Not a surgeon, no. Have you heard of Trauma Redemption Services?” she asks, the laugh leaving her body.

And I have. Of course. It’s all the rage for the wealthy. I’d talked to people who’d had it done. They often came to empathy trainings, ran businesses, would ask me if I thought the procedure would make them less empathetic or more.

The theory behind Trauma Redemption was that if you had a traumatic memory erased, you’d lose something fundamental. So they gave it to someone else. It was taken from their mind and implanted into someone who would sit in front of them, letting the memory run through them, as the person watched. The person who had the memory now had to keep it. In case the giver ever wanted to recall it, wanted to talk through what had happened again, wanted to relive it on someone else’s face.

“I have. What do you do with them?” I want her to be someone in the office, someone who typed up reports or moved finances around.

She looks out the window again, and her reflection on the glass looks younger. “The first one I ever did was someone who had crashed his car. Crashed the car right into someone else. He said to me, ‘I never saw her.’ But in the memory, he did. I wondered if he wanted me to know. If he wanted to forget, but wanted to know that someone else knew?”

I don’t say anything. And when she turns back to me, she still has Halley’s face. It’s older and sadder and lost in a moment of thought. But it’s Halley. She smiles at me. “I have a procedure tomorrow. It’s why I’m here actually. For some clients, we’ll travel. I’d like you to see the procedure.”

“Me?”

“Yes. I looked you up after we met in that café. Saw what you do for a living. It sounds like it might be an interesting thing for you to see, help your work.”

I don’t say, But I never gave you my last name. I don’t say, How did you find me? I just stare at her and remember when we were twelve and it was my birthday party. Halley was eating cake and she started crying. I ushered her into my room and asked what was the matter. She was sad because she had been eating my birthday cake and had looked up and realized that I was getting older and she said What if we keep getting older and we move away and we eventually start talking less and less and what if we aren’t friends in the future.

And I said, But we’re friends forever, Halley.

And she’d said, Promise?

“Okay, sure,” I say.

Faye smiles. And then she changes the subject, begins talking about a movie she saw recently. We make small talk for another thirty minutes or so. Then she writes down an address and time and slips me the piece of paper. Her handwriting is perfectly straight and neat, like someone trying to write in a way that wouldn’t be recognized.

“Oh, it’s not creepy by the way. I saw the building you walked into after you left with your coffee. The company name. Only one Abby works there. The miracles of modern search capabilities.” She picks up her purse carefully. “You can find anyone.” She leaves before I respond.

I count stars. Think about the constellation Halley had named after Persephone. She’d said, that one looks like it wants to run but she can’t. I said, isn’t that a myth about balance? Like we can’t always have spring and we can’t always have winter. Halley shook her head, it’s a story about trying to forgive. She didn’t explain. But every sleepover after, she’d trace the constellation with her fingers. On nights she isn’t there, I do it for her.

Halley in my bedroom, stretching over the bed, about to ask me a question.

“Please don’t forget tomorrow.” A text arrives and I don’t answer. But I think she must know I’ll be there.

My brother sends me a message, asking how it went. I want to tell him everything, but I don’t want him to worry. I don’t think it’s her, I type out. But I never hit Send.

Once, when we were in our twenties, we watched a movie in which a young girl is kidnapped. It’s violent, She screams and fights, but she’s still snatched up and forced into a van. I didn’t realize I was crying until my brother had placed a hand on one of my shoulders. So gentle I almost didn’t feel it. I’d turned to him and he’d had tears in his eyes too. I never asked him if he was thinking about Halley or if it was only because he was worried about me. She used to call him Bro, every time she came over. She was at our house so often, it felt true.

It might be her, I type out. I hit Send.

I call out from work. The first time I’ve used a sick day in years. In the morning, I pace the kitchen, sipping the same cup of tea for hours.

There are no messages from her. I wonder if she wants to see if I’ll really come, if she worries that pressure will make me stay away. I watch a video about monster movies, how creature effects evolved over time. It’s background noise, but I find myself listening when a makeup artist talks about how hybrids scare us. “If something is close to something we know already, but not quite it, it makes us nervous. It’s like the uncanny valley, you can be far away from being a human in looks and we’ll be fine with it—a happy little robot, all beeps and boops, and square frame. But make it almost human, have fingernails, and teeth, and smile at us when we smile, but only then, never on its own, and suddenly we’re terrified.”

In university I designed a program that seemed like a simple game from the outside. You created an avatar based on a photograph of yourself, then you entered a little game sphere. You answered trivia questions, and a little robot on the screen would smile or frown depending on whether you got the answer right or wrong. But as you got deeper into the game, the robot began to look more and more like the game player. At first the changes were simple—the cartoony robot would get the player’s eye color. But the game became more elaborate the more you played, and the robot’s face shifted to the shape of the player’s face. At the end, the player was playing a cartoon version of himself. My professor gave me an A, but he said he didn’t understand the concept. I hadn’t really known myself. Only that when I played the game, I never used my own photo. I used photos of people I loved. In the end, my mom or dad or my brother would be smiling at me when I got answers right. I never used photos of Halley.

The building could be anything. Just a rented-out office in the middle of the city. The café next to it is bustling, another office suite is filled with an accountant’s office. I walk past to the elevator and go up to the seventh floor. A receptionist is dressed in a simple black dress. She smiles at me and asks my name. “Oh, you’re Faye’s guest, right?” I nod.

“Awesome! We don’t usually have viewers, but she said your company is thinking of working with us? That would be so cool. Trauma and empathy go hand in hand.”

“Not really,” I say. But the receptionist is already not looking at me, instead playing a game on her phone. Tiny birds fluttered across her screen, diving to get coins that were falling alongside them.

I take a seat and wait. If I had gone to work today, I’d be just about on my lunch break. If I’d never said yes, I’d send my brother a photo of a coffee that I got from the place where the barista always swirled the foam into flowers, into the night sky, into anything he could think of. If I’d never gone to the diner, I’d be somewhere else. If I’d never been at that bar and I’d never seen her, I’d point out Persephone every night until one night when I forgot. If, if, if. Halley would finish walking home and she’d be home and we’d talk the next day about the football game and she’d lean over and tousle my brother’s hair and say good job, Bro. And he’d let her. Only her.

“You can go back now,” the receptionist says. And I follow her to a room that looks like an office, except it’s been divided in two by a glass partition. A woman sits across from Faye. They both are on simple office chairs, and there’s nothing between them. They are close enough their knees almost touch. A man in a lab coat stands to Faye’s right. He holds something that looks like a cross between a needle and laser pointer.

The receptionist sits next to me. “Let me know if you need anything. These sessions can be hard to watch the first time.”

“Only the first time?”

She shrugs, “You can get used to anything.”

“What’s the trauma?” I’m not sure I want to know, but I have to.

“The woman was kidnapped when she was a child. She has nightmares about it still. I don’t know why she waited so long to have it removed.”

The man in the lab coat moved next to Faye, pushed her hair away from one side of her head and I see a small metal plate right behind her ear. He uses one side of the device to pop the plate open, but I can’t see if it’s skull behind it or what. And then he places the device against her head and presses a button.

I watch her face. At first it’s pain and then it’s fear, and she cries and she cries. The woman watches her blankly. But the more Faye cries and pleads, the woman shifts in her seat, until she finally reaches out and takes hold of Faye’s hands. She holds them gently as the rest of the memory floods through her. And then it’s over. Faye’s head droops, she stays sitting, and the man in the lab coat talks to the woman for a few minutes. They shake hands and another woman enters the room and escorts the client out. I can’t believe there’s not more. That she doesn’t stay to ask Faye questions. If the memory is gone, does the woman feel free?

“It’s over?” I ask the receptionist.

She nods, smiling. “So simple, right?”

I ask where the restroom is and once inside I brace myself against the sink. My hands shaking so hard I can barely grip. I look up and Faye is behind me. Her face watching mine in the reflection. And her face is Halley’s face. Older. I try to look for laugh lines but I can’t find them.

“How can you do that?”

She steps closer to me, until she’s standing at the adjacent sink. She turns on the water. She rolls up her sleeves a little, and I see scars on her forearms, so many scars. “They’re not my memories. I’m just holding them.” She splashes her face with cold water. Grabs a paper towel and begins drying herself.

“Halley?” I almost whisper it.

She shakes her head. “I’m not her.”

“I lost her.”

“I’m sorry,” she says. “Maybe our services could help you, too?”

She reaches out and touches my hand. Just for a second. As she takes her hand away, I see a tiny tattoo etched in the hollow of her wrist. A pomegranate. She sees me looking. “After Persephone. Do you know that myth.”

I nod. “It’s about forgiveness.”

She smiles at me oddly, as if I’ve said something obtuse. “That’s a strange interpretation,” she says. And then she leaves. If she turned back, if she reached out again, if she whispered that promise, if she walked back to her office and back through her life until she was at the football game and she waited for me, she’d come with us, we’d eat ice cream, let it melt in our mouths, so sweet and cold. If, if, if she was Halley. If.

She doesn’t come back into the bathroom. It’s just me and the sink and the mirror. If I study my reflection in the mirror long enough, maybe I won’t know who I’ll recognize looking back at me.