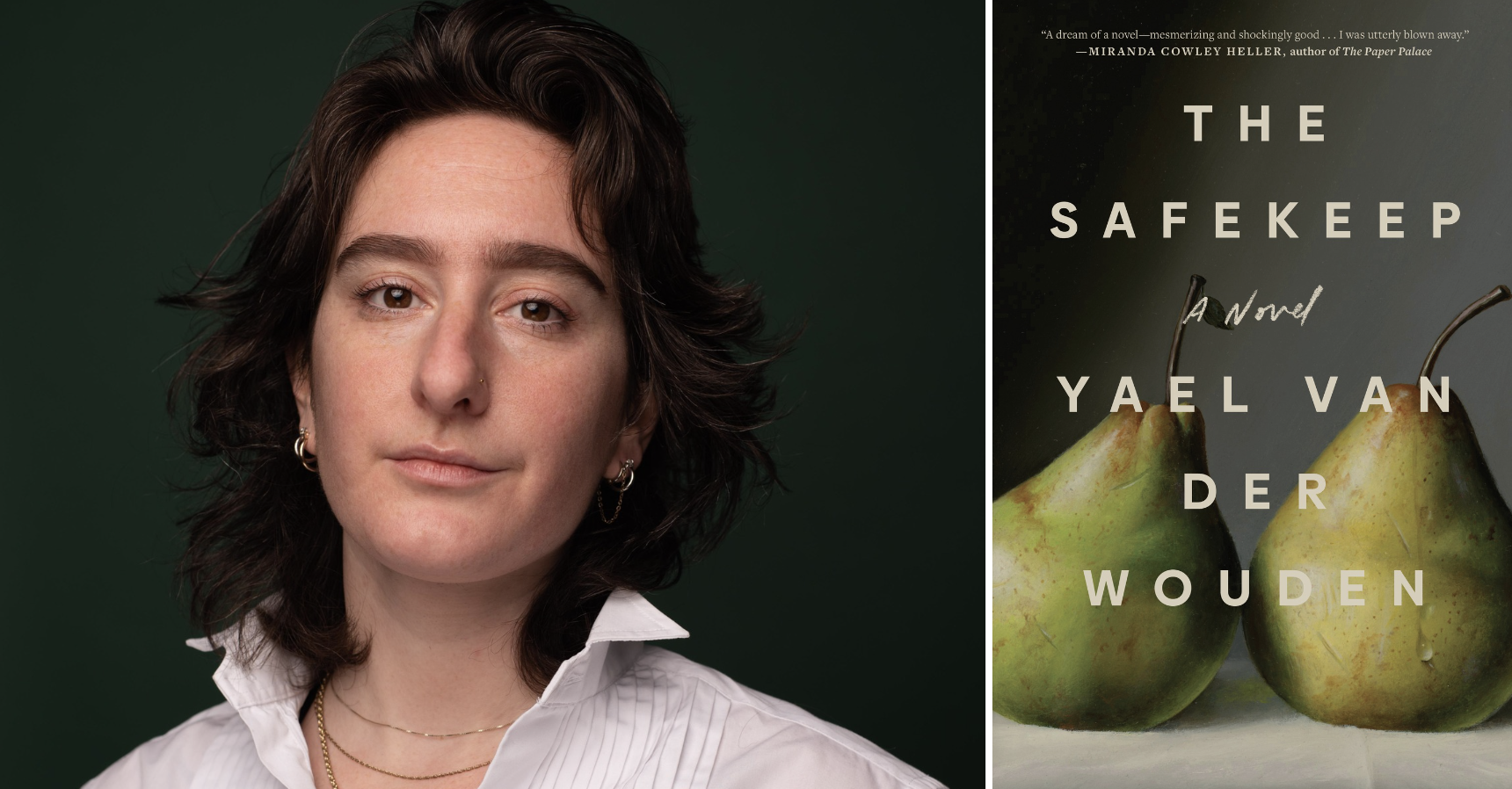

In her debut novel, The Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden writes a tense, sensuous, and expertly-plotted tale of two women in post-WWII Netherlands who are thrust into a close-quartered and tempestuous relationship with each other. The novel is at once a historical reconciliation, an empathetic character study, a mystery, and a love story, all delivered in van der Wouden’s impeccably-wrought prose. I read The Safekeep in a few breathless sittings—it’s one of those books that once you begin reading you find any excuse to keep doing so.

I talked with van der Wouden about complicity, the lure of the tactile, and what makes a good sex scene.

*

Julia May Jonas: I’m firstly interested in your personal literary history—where does this book land in your trajectory of life as a writer?

Yael van der Wouden: It’s still a miracle to me that I’ve ended up where I’ve ended up. I wasn’t a big reader as a child, only ended up reading in my early teens because of chance—stuck at my grandparents’ house in the middle of the forest with nothing to do but read. I didn’t do well in school. I had no business wanting to go places like university. But I was stubborn, and crawled my way up.

For as long as I’ve been reading I’ve been writing. The two came hand in hand: I’d read a book, and then try to write something similar. There’s 13-year-old me’s version of a magical-school novel, there’s 15-year-old me’s version of a Nick Hornby novel. This book feels like both the culmination of everything that came before and also a complete stroke of luck. What if we hadn’t moved in with my grandparents? What if I hadn’t passed that one test that got me into university? What if I hadn’t gone on that vacation where I stayed in that one house, wrote that short story, what if the first readers had hated it and I’d have slunk away in shame? It’s relentless work and pure chance, somehow all at once.

JMJ: And with this book—what was the seed of the idea and how did it develop?

YvdW: I have this rant that I often trot out at parties, about living as a Jewish person in the Netherlands and how it feels like being a ghost haunting its old home, how the skeleton of what used to be is still there—the homes of Jewish people, certain Jewish customs that infiltrated into Dutch culture—but the people themselves are gone. The novel got to stew in that water for years before I put pen to paper.

JMJ: You have lived in both the US and the Netherlands—I was curious about where you were living when you wrote this book? Did your location influence the book itself?

YvdW: I was living in Utrecht, in the Netherlands, though the book takes place near Zwolle—a city in the east of the country where my parents live, and where I grew up—but actually most of the novel was written on trains over the course of a feverish six months. I’d be teaching in Maastricht, which is two hours away, so that became my writing time. The Dutch landscapes stretched out for ages outside, and it was autumn and the frosted flatlands during sunrise were absolutely gorgeous. But also I cannot handle the winter, so most of the novel is a yearning love letter to the summer.

JMJ: The book explores the history of the Netherlands during the aftermath of the Holocaust. As a Dutch writer, what did you particularly want to explore about the country you grew up in and its relationship to this history?

YvdW: I’ve spent so much time here in this country being absolutely furious. Everything is quaint and pretty and life can be relatively peaceful, but at the same time it has such a deeply violent history: through the Holocaust, yes, but also its colonial history. If you read accounts of how the Dutch conducted themselves on their former colonies, especially Suriname and especially as enslavers accounts often reflect on how no one was as cruel as the Dutch. No one was as inventive in their cruelty as the Dutch. I think in writing this novel I was trying to understand complicity and conformity through small life, through the perspective of one singular person: Isabel. And then, of course, once I’ve created an environment where even I could understand this character’s motivations, the joy was in upending her. It was me having a conversation with myself, with both my Jewishness but also my Dutchness.

JMJ: Your main characters, both vivid and striking women, are very different: routine/ritual-obsessed Isabel, and messy, vivacious Eva. Could you say more about how these characters emerged, how you created them and then put them into (thrilling) relationship with one another?

YvdW: I wrote a short story at the beginning of the pandemic during a writing workshop titled “Louis’ New Girl” about three siblings out for dinner, and one of the sibling’s annoying new girlfriend. Isabel emerged nearly fully formed from that short exercise: a repressed, judging woman whose personality obscures a deep well of desire. Her dynamic with Eva was there from the start, even before the plot took shape. I am fascinated by/obsessed with how narratives of what femininity should be can express themselves in either desire or disgust: I hate her, I want to be her, I want to give her a makeover, whatever. Both Isabel and Eva have ideas of womanhood, which at first make them repellant to one another. The joy was of course to turn that repellant into desire, to queer the oftentimes deeply hetero slant of internalized sexism.

JMJ: Your book feels very physical—the physicality of the house, of the objects, and then the physicality and sexuality of the characters themselves. I felt a strong link between the house and the bodies inside the house—as the home is disrupted, the bodies are disrupted. What were you exploring in the relationships between buildings and things and bodies?

YvdW: I’m a very tactile person. As a kid I’d need to touch everything first before I let it come close—handle the fruit, brush a piece of fabric across my lips to feel if it was soft or not. When we moved in with my Calvinist grandparents this was very quickly reprimanded, because your fingers and dirty and your mouth is dirty. If you must touch a fruit, you do so only to pick it up, and you never lay it back down in the bowl with the other fruit. I think for a while I came to understand touch as excess, as something good but forbidden. Isabel has so much desire: to be loved, to love, but also a desire to control her environment; I wanted to shift that desire from “you mustn’t touch” to “touch everything.” This means bodies, yes, but also things—the house, the walls, the dirt in the garden. There’s plenty of things you can dig your fingers into.

JMJ: The Safekeep is teeming with sexuality, and the sex scenes are written so well and with such care—how did you do this and what were your aims with writing them?

YvdW: I think this harkens back to the question of touch, and the tension of what you forbid and what you allow. If you write a hundred pages of a character who doesn’t allow herself touch, then the moment you allow her to grab a living person—Eva’s elbow, if you recall—then that tension will naturally transition into the erotic. A good sex scene has so little to do with the movements and positions and so much more to do with how you got there, what the characters want from each other and what the stakes are. In this case, the trick is also to resolve nothing internal in that sex scene: only the sexual desire is sated, but the plot tension, the characters’ wants, those remain. You’ll notice: once the plot is resolved, we are no longer privy to the sex. The moment the sex turns gratuitous you lose the tension, and therein the emotional investment of your readers.

JMJ: To that end, your book, while set in the aftermath of unspeakable horror, is a story about love. Did you know you wanted to write a love story when you began?

YvdW: Yes! It was always going to be a love story. I am a sap. There’s also something terribly selfish about it, writing “bad” characters that find love. You’re basically mumbling to yourself, “It’s okay, even if I’m sometimes bad, even I can find love!” But also, more importantly, I wanted to write a story where the answer to past prejudices wasn’t an apology and mild tolerance, but desire—so much desire that the only path forward is together, entangled.

JMJ: Finally, there’s a great hopefulness to the book. What is your relationship to hope, as a writer and also as a human?

YvdW: This is perhaps an unpopular opinion, but I think it’s so, so much more impressive when a hopeful ending is made to feel true, like a real possibility. It’s harder than making a sad ending feel true and possible—that’s life. That’s more or less my relationship to hope, I think. It’s hard work, but God, isn’t it impressive when it works?