“Don’t you want to write a real book?” This is a question that’s been posed to many of my YA author friends. It’s also a question—with its implication that real books are for adults—that betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of what YA is and why it matters.

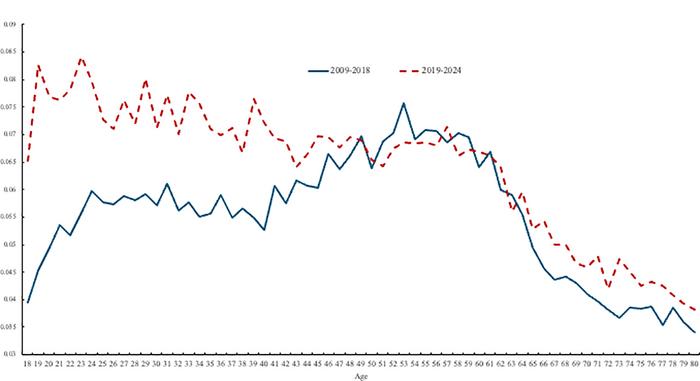

An argument could be made that, simply put, YA is for young people, not adult readers. This line of thinking also seems to diminish its value: the genre’s commercial success (YA book sales hit $11 billion globally in 2022) hasn’t translated into—and is perhaps directly at odds with—literary prestige, and it remains more difficult for YA authors to be considered for tenure-track teaching positions, covered in literary journals, and so on. But the category’s true audience is deceptively broad. More than half of the people buying YA books today are over 18 years old—and the majority of those buyers are between 30 and 44 years old. If you’re thinking these adults are buying books on behalf of tweens, teens, or perhaps educators bulk buying for adolescent or college-aged students, the truth is much more interesting. The vast majority—78%—of YA buyers over 18 are specifically purchasing YA books with the intention of reading them themselves.

Adult readers’ growing interest in YA can be partly chalked up to the internet. Online, adults can shop somewhat anonymously, without judgment. They can also more easily find niche fandoms and forums suited to their passions. With social media, we’re attuned to the thoughts of more individuals than, one might argue, we were ever meant to know. But with it, a blessing: the ability to create and join communities that share our interests. This is especially useful at this pressure point in history, when both legal and unwritten restrictions are at an all-time high where books are concerned.

We live in an age steeped in nostalgia, with podcasts dedicated to rewatching old TV series, remastered classic video games made available for digital download, books we loved when we were young being reprinted with new covers. With so much uncertainty and fear in our present reality, adult readers have every reason to seek comfort in the familiar. Consider the recent resurgence of adult Judy Blume fans with the film adaptation of Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. The movie welcomed young fans into a cult classic and invited older generations to reconnect with themselves. It brought different demographics together in a simultaneously timely and timeless space where they could see themselves in each other.

We live in an age steeped in nostalgia, with podcasts dedicated to rewatching old TV series, remastered classic video games made available for digital download, books we loved when we were young being reprinted with new covers. With so much uncertainty and fear in our present reality, adult readers have every reason to seek comfort in the familiar. Consider the recent resurgence of adult Judy Blume fans with the film adaptation of Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. The movie welcomed young fans into a cult classic and invited older generations to reconnect with themselves. It brought different demographics together in a simultaneously timely and timeless space where they could see themselves in each other.

When you revisit a book you love later in life, don’t you find something new? Sometimes that new thing is the old you. I find that, to that end, YA books don’t exist solely for young people, even if that’s who they’re written for.

In general, adult literature is less concerned with the story of becoming in a linear, developmental sense; even when an adult novel speaks to the teen experience, it’s not intended to speak specifically to teen readers. Broken down plainly, we might say adult literature centers adults—including those reflecting on their youth—and YA centers young adults. What, then, can we make of adult fiction and nonfiction with young adult or even child protagonists?

There is so much urgency and experimentation to be found in the teen-centric subset of adult literature. In the case of Joseph Earl Thomas’s adult memoir Sink, our third-person protagonist is a child under the age of 13—a book marketed to adults that doesn’t center on an adult. It’s a gripping coming-of-age memoir wherein Thomas deftly, selectively detaches himself as the author from his protagonist counterpart, never shying away from the complexities of poverty, violence, and geek culture. It begs the question: When we have a child or teen at the center of a story, is the categorical difference between YA and adult in the plot, the stakes, or the voice and tone? Do books have a tell?

There is so much urgency and experimentation to be found in the teen-centric subset of adult literature. In the case of Joseph Earl Thomas’s adult memoir Sink, our third-person protagonist is a child under the age of 13—a book marketed to adults that doesn’t center on an adult. It’s a gripping coming-of-age memoir wherein Thomas deftly, selectively detaches himself as the author from his protagonist counterpart, never shying away from the complexities of poverty, violence, and geek culture. It begs the question: When we have a child or teen at the center of a story, is the categorical difference between YA and adult in the plot, the stakes, or the voice and tone? Do books have a tell?

I don’t believe so. At least this holds true for me as a reader, and delightfully so, as in the case of YA novels like Patricia Park’s Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim. In it, Park tells the coming-of-age story of a multicultural teen on scholarship at a privileged private school in New York City. With every bit the drama of an adult novel—a father’s depression and probable suicide, a mother who works too hard to make rent and repeatedly refuses her daughter’s dreams, and a teenager shouldering the weight of her clashing internal and external worlds—Imposter Syndrome ripples just as far and deep with the quality of its words and the accessibility of its storytelling.

I don’t believe so. At least this holds true for me as a reader, and delightfully so, as in the case of YA novels like Patricia Park’s Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim. In it, Park tells the coming-of-age story of a multicultural teen on scholarship at a privileged private school in New York City. With every bit the drama of an adult novel—a father’s depression and probable suicide, a mother who works too hard to make rent and repeatedly refuses her daughter’s dreams, and a teenager shouldering the weight of her clashing internal and external worlds—Imposter Syndrome ripples just as far and deep with the quality of its words and the accessibility of its storytelling.

In truth, “accessible” is a trigger word for me, one I’ve heard often in relation to my own writing. Depending entirely on who’s doling it out, “accessible” can be a compliment or an insult. The more I write and publish, the more I choose to take it as the former. I want to give readers access. Yet I’ve also published poems one might consider “literary,” which often simply means in outlets that are widely read and lauded by other published writers. Even now, I struggle to define my terms. I’m a poet of plainer inclinations. I prefer to detail the image as precisely as I can, the way an essayist might—to narrate my poems rather than let them sing. I break my lines and I hope my good-faith readers enjoy them, whoever they are.

Last summer, my book Disappearing Act, a memoir-in-verse categorized as YA and written from the perspective of my teen self, was published. The book could have taken the shape of an adult memoir, perhaps as a traditional retrospective or as an experimental series of essays with an epilogue that charts my journey from then to now. But it was important to me that teenagers had as few barriers to my story as possible. YA, in that sense, was the right shelf.

Last summer, my book Disappearing Act, a memoir-in-verse categorized as YA and written from the perspective of my teen self, was published. The book could have taken the shape of an adult memoir, perhaps as a traditional retrospective or as an experimental series of essays with an epilogue that charts my journey from then to now. But it was important to me that teenagers had as few barriers to my story as possible. YA, in that sense, was the right shelf.

The subject matter itself is heavy, with my own coming of age set against the backdrop of my father’s suicide attempt and incarceration. I was the teen who lived the events I described, but there are adults, teens, and children having a version of my experience every day in America. Fortunately and in a way that defies book marketing, adults read down and children read up. I wrote with both audiences in mind, but there is yet to be an organic way to reach both audiences.

There are countless adult books that feature fully realized young characters, such as Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, Sarah Manguso’s Very Cold People, Sara Nović’s True Biz, Stephen King’s Carrie, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. Just as there are countless YA books that feature the lyricism, stakes, and story we revere in adult literature, such as George M. Johnson‘s All Boys Aren’t Blue, Ariel Henley’s A Face for Picasso, Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X, Mary H. K. Choi’s Yolk, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, and so on.

There are countless adult books that feature fully realized young characters, such as Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, Sarah Manguso’s Very Cold People, Sara Nović’s True Biz, Stephen King’s Carrie, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. Just as there are countless YA books that feature the lyricism, stakes, and story we revere in adult literature, such as George M. Johnson‘s All Boys Aren’t Blue, Ariel Henley’s A Face for Picasso, Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X, Mary H. K. Choi’s Yolk, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, and so on.

If the adult literary landscape doesn’t make room in the conversation for the ever-growing adult audience of YA readers, we run the risk of excluding the communities many of us hoped to cultivate in adulthood when we were young. YA reflects us back to ourselves, embodying a basic truth: We’re always coming of age—at every age.