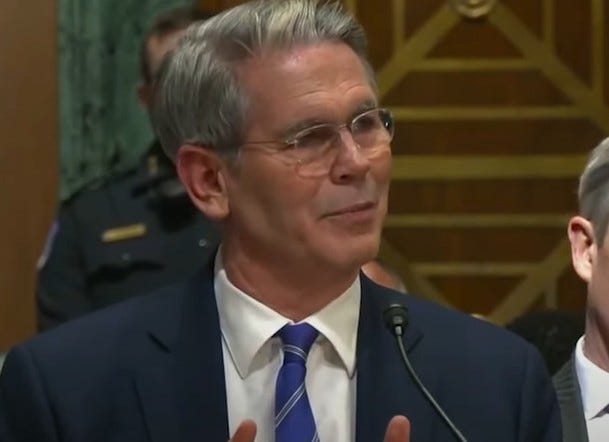

The Trump presidency, Martin Amis said, was “a daily unreality, a daily insult.” We were sitting across from each other in a Brooklyn bar as I interviewed him for the third—and as it turned out—penultimate time. And unreality is what I still feel weeks after learning of Amis’s death at the age of 73.

Money, Amis’s great novel of 1980s excess, is where I started with his work. I know—it’s the one everyone loves, by which I mean it’s the one young men love. Well, I was a young man when I read it for the first time, and I remember being astonished that anyone would tell them—that is, women—the truth of how appallingly atavistic and self-interested men at their worst can be.

Money, Amis’s great novel of 1980s excess, is where I started with his work. I know—it’s the one everyone loves, by which I mean it’s the one young men love. Well, I was a young man when I read it for the first time, and I remember being astonished that anyone would tell them—that is, women—the truth of how appallingly atavistic and self-interested men at their worst can be.

Money is narrated by John Self, a comically hedonistic British director of TV commercials who stumbles through high and low life in New York and London as he attempts to make his first movie. That mostly means booze, cocaine, pornography, massage parlors, and the like. I can’t imagine a woman loving Money quite as much as men. I suspect this is because women might sense that some men read the novel with a whiff of admiration for the male id gone wild.

Money is a comic novel, but it takes on an increasingly poignant quality as the narrative unfolds. Here’s John Self’s describing the pain of ignorance:

Oh Christ, the exhaustion of not knowing anything. It’s so tiring and hard on the nerves. It really takes it out of you, not knowing anything. You’re given comedy and miss all the jokes. Every hour you get weaker. Sometimes, as I sit alone in my flat in London and stare at the window, I think how dismal it is, how heavy, to watch the rain and not know why it falls.

Toward the end of the novel, as Self begins to educate himself, he reads history for the first time—and it’s a revelation:

As for Hitler, well, I’m consternated. I can’t fucking believe this stuff. Look how far he spread his violence. And I thought I was aggressive. Boy, Germany must have had some dizzy spell or drunk on, in the Thirties and Forties there, to have given headroom to a sick little gimp like him. I’m consternated. I can’t believe this stuff. And you’re telling me it’s true?

Amis called Money his “talent novel” because it’s where he found the exuberant style that marked his bountiful middle period. One of Amis’s literary heroes, Saul Bellow, famously said that when writing his own notable talent novel, The Adventures of Augie March, the language flowed as if from an open fire hydrant. All he “had to do was be there with buckets to catch it.” Money was like that for Amis, and the result is a thrilling freedom and fearlessness on the page.

Amis called Money his “talent novel” because it’s where he found the exuberant style that marked his bountiful middle period. One of Amis’s literary heroes, Saul Bellow, famously said that when writing his own notable talent novel, The Adventures of Augie March, the language flowed as if from an open fire hydrant. All he “had to do was be there with buckets to catch it.” Money was like that for Amis, and the result is a thrilling freedom and fearlessness on the page.

One way I rate novels is by the number of checkmarks I make in the margins as I read; my copy of Money, as you might guess, is lousy with checks. As I looked through it searching for favorite passages, however, I realized that the allure of Amis’s fiction is never its plot—it’s the language.

Money along with 1989’s London Fields and 1995’s The Information have come to be known as the London Trilogy, and these works are often cited as prime Amis. But that leaves out some of Amis’s best stuff, including Night Train, Amis’s version of an American police novel.

Money along with 1989’s London Fields and 1995’s The Information have come to be known as the London Trilogy, and these works are often cited as prime Amis. But that leaves out some of Amis’s best stuff, including Night Train, Amis’s version of an American police novel.

Night Train is narrated by a female detective, “a police” as she calls herself. Once again, the plot—the investigation of the inexplicable suicide of a seemingly healthy, brilliant, beautiful woman—is the last thing I think about as I recall the fantastically enjoyable reading experience of Night Train, as in this early passage:

Allow me to apologize in advance for the bad language, the diseased sarcasm, and the bigotry. All police are racist. It’s part of our job. New York police hate Puerto Ricans, Miami police hate Cubans, Houston police hate Mexicans, San Diego police hate Native Americans, and Portland police hate Eskimos.… Anyone can become a police—Jews, blacks, Asians, women—and once you’re there you’re a member of a race called police, which is obliged to hate every other race.

Late in his career, Amis turned to history, as do many older writers. For him, this meant the history of “the big mustache” (Stalin) and the “small mustache” (Hitler). When I interviewed Amis for the last time, he explained that writing historical fiction was a “defense mechanism” against losing touch with the zeitgeist, a problem his father, the comic novelist Kingsley Amis warned him about:

My father [said] to me, ‘There’s a point in a writer’s life when you’re getting old when you suspect that it isn’t like that anymore. Your everyday consciousness is not the everyday consciousness of 30 year olds today, obviously. ‘It’s not like that anymore—it’s like this.’ That’s what the young writers naturally say to the old writers. So history is an escape from that bind, as well as being incredibly interesting.

House of Meetings, published in 2006, stands out among these late historical novels. It’s a hugely ambitious work narrated by a Russian-born, decorated veteran of WWII who “raped my way across what would soon be East Germany,” and later did time in the Russian Gulag. There’s also a love triangle involving the narrator, his ruined pacifist brother—also a veteran of the Gulag—and the Jewish woman they both love. The novel takes the form of a long, arch, epigrammatic letter to the narrator’s American stepdaughter, Venus, and it’s filled with sentences like this:

House of Meetings, published in 2006, stands out among these late historical novels. It’s a hugely ambitious work narrated by a Russian-born, decorated veteran of WWII who “raped my way across what would soon be East Germany,” and later did time in the Russian Gulag. There’s also a love triangle involving the narrator, his ruined pacifist brother—also a veteran of the Gulag—and the Jewish woman they both love. The novel takes the form of a long, arch, epigrammatic letter to the narrator’s American stepdaughter, Venus, and it’s filled with sentences like this:

So you see, Venus, the peer group can make people do anything, and do it day in and day out. In the rapist army, everybody raped. Even the colonels raped. And I raped too. There is a further mitigating circumstance: namely the Second World War, and four years on the dirtiest front of the dirtiest fight in history. Don’t apply zero tolerance—a policy that calls for zero thought.

So, no, it’s not a fun read, but a thrilling one nonetheless. It’s one of those works of fiction that never feels willed into being. Instead, it’s compulsively told, as in this dark warning: “When a man conclusively exalts one woman, and one woman only, ‘above all others,’ you can be pretty sure you are dealing with a misogynist. It frees him up for thinking the rest are shit.”

Besides his 15 novels, Amis also published a stunning amount of dauntingly erudite literary criticism, collected in five volumes. I say “daunting” because Amis seemed to hold all of English literature—and modern American literature—in his head. He wrote essays, introductions, and reviews that treat Austin, Milton, Dickens, Donne, Waugh, Joyce, Wodehouse, DeLillo, Updike, Naipaul,Burgess, Pritchett, Ballard. And I counted at least a dozen admiring pieces on the writers he calls the “Twin Peaks” of his personal canon, Nabokov and Bellow. Amis is especially entertaining when, early in his career, he sized up—and in some cases took down—his American elders. This is from his encounter with Truman Capote who was in the midst of a very bad day:

Then, from the gloom at the end of the passage, emerged the helpless, tottering figure of Mr. Capote, who let out a soft wail of greeting and extended a tiny hand. For pity’s’ sake, I wanted to say –never mind the interview. Let’s call an ambulance. Or I can take him there in my briefcase.

And here’s Amis on how the enormous success of Norman Mailer’s first novel, The Naked and the Dead, affected Mailer’s subsequent career:

And here’s Amis on how the enormous success of Norman Mailer’s first novel, The Naked and the Dead, affected Mailer’s subsequent career:

Early acclaim won’t harm a writer if he has the strength, or the cynicism, not to believe that acclaim. But Norman lapped it up. …[The Naked and the Dead] was impossibly adult: the immaturity was all to come.

In more recent years, Amis was equally tough—or should I say insightful?—on Philip Roth:

Well, Sabbath’s Theater isn’t funny. That gulping and cracking you hear coming off the page may sound like laughter, but hysteria is never funny. As a spectacle, hysteria is embarrassing, then alarming, then depersonalizing. All hysteria does is sustain itself until it exhausts itself. In this novel Roth conducts an amazing tantrum: a tantrum directed at that tragic duo, sex and death. Halfway through the book you begin to think: yes, this is what morbid erotomania must feel like.

Of course, Amis is no mere take-down artist. He also has nice things to say about Capote, Roth, Mailer, and many others. His highest praise, however, is reserved for the author of The Adventures of Augie March, which Amis repeatedly argues is the great American novel: “Bellow sees more than we see—sees, hears, smells, tastes, touches. Compared to him, the rest of us are only fitfully sentient; and intellectually, too. His sentences simply weigh more than anybody else’s.” The same might be said for Amis.

Despite Amis’s brilliance and at times caustic wit, he was, in my limited experience, a generous presence. I have a very pleasant memory of the final moments of our Covid-era Zoom conversation about Amis’s last published novel, Inside Story. Recalling that I’d mentioned that House of Meetings is my wife’s favorite of his novels, Amis signed off in what he himself described as his “posh” accent this way: “So long. I offer you an elbow. And give my best to your wife.” The man had manners.

Despite Amis’s brilliance and at times caustic wit, he was, in my limited experience, a generous presence. I have a very pleasant memory of the final moments of our Covid-era Zoom conversation about Amis’s last published novel, Inside Story. Recalling that I’d mentioned that House of Meetings is my wife’s favorite of his novels, Amis signed off in what he himself described as his “posh” accent this way: “So long. I offer you an elbow. And give my best to your wife.” The man had manners.

Inside Story is a curious mix of recollections of Bellow, Christopher Hitchens, and Philip Larkin, combined with a fictional love affair, as well as superbly intelligent instructions on how to write well. Like I said, a curious mix. “Never use any phrase that bears the taint of the second-hand,” Amis advises at one point in the book. “Shun all vogue phrases, shun all herd words; detect them early on and shun them.” Elsewhere in Inside Story, he laments the declining audience for “long, plotless, digressive, and essayistic novels (fairly) indulgently known as ‘baggy monsters.’” The readers for such novels, he fears, “are no longer there—their patience, their goodwill, their autodidactic enthusiasm are no longer there.”

But I believe—or perhaps I hope—that Amis is wrong, and that there will always be an audience for the great pleasure to be had from reading his dense, droll, wonderfully discursive sentences; and that readers and writers alike will continue to be fortified by his insistence that, as he once phrased it to me, “Writing is freedom and to hell with everything else.”

That’s worth repeating as we remember Martin Amis. Writing is freedom. Writing is freedom. Writing is freedom.

“Martin Amis in León Spain in 2007” by Javier Arce is licensed under CC BY 2.0.