As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene on multiple choice tests. In the spring semester of 2004, I was more concerned with Yuengling than I was with Geoffrey Chaucer or the Pearl Poet, so I fully deserved the middling grade that I got.

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene on multiple choice tests. In the spring semester of 2004, I was more concerned with Yuengling than I was with Geoffrey Chaucer or the Pearl Poet, so I fully deserved the middling grade that I got.

Yet that class was also the site of an important discovery: the stern, austere, blind Puritan bard John Milton. For the past two decades, I’ve read and reread Milton, written about Milton, taught Milton, thought about Milton. I don’t know if I’m any closer to really understanding his greatest work, for that magisterial 1667 poem Paradise Lost is a cosmos unto itself, like Dante’s The Divine Comedy or Melville’s Moby-Dick, but I know that my life wouldn’t be as rich without it.

Yet that class was also the site of an important discovery: the stern, austere, blind Puritan bard John Milton. For the past two decades, I’ve read and reread Milton, written about Milton, taught Milton, thought about Milton. I don’t know if I’m any closer to really understanding his greatest work, for that magisterial 1667 poem Paradise Lost is a cosmos unto itself, like Dante’s The Divine Comedy or Melville’s Moby-Dick, but I know that my life wouldn’t be as rich without it.

“Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit / Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste / Brought death into the world, and all our woe,” intones the poet in Paradise Lost, still resonating across nearly three-and-a-half centuries, a writer who even when he is dry or slow (and he can be dry and slow) still can turn a phrase and deploy it to stunningly dramatic effect in this epic tale about Satan’s rebellion against God in Heaven and the subsequent fall of humanity and all Creation. Having been the sort of affected English major who took to Moleskine notebooks and cracked-spine copies of Charles Bukowski and Chuck Palahniuk rather than John Donne and George Herbert, Milton wasn’t my ideal author nor I his ideal reader. Regardless, ever since found him deep within the recesses of the Norton Anthology of British Literature, the bible-paper pages of which would absent-mindedly flip through during class, I’ve been singularly drawn to Milton, this man from a period so foreign to my own, whose faith is so alien to me. Since first encountering Milton, I’ve felt my relationship to the poet has somewhat mirrored that old story from Genesis, of Jacob wrestling an angel only to exit the encounter with a new name, except I keep reading Paradise Lost in hopes of discovering what that name might be.

“Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit / Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste / Brought death into the world, and all our woe,” intones the poet in Paradise Lost, still resonating across nearly three-and-a-half centuries, a writer who even when he is dry or slow (and he can be dry and slow) still can turn a phrase and deploy it to stunningly dramatic effect in this epic tale about Satan’s rebellion against God in Heaven and the subsequent fall of humanity and all Creation. Having been the sort of affected English major who took to Moleskine notebooks and cracked-spine copies of Charles Bukowski and Chuck Palahniuk rather than John Donne and George Herbert, Milton wasn’t my ideal author nor I his ideal reader. Regardless, ever since found him deep within the recesses of the Norton Anthology of British Literature, the bible-paper pages of which would absent-mindedly flip through during class, I’ve been singularly drawn to Milton, this man from a period so foreign to my own, whose faith is so alien to me. Since first encountering Milton, I’ve felt my relationship to the poet has somewhat mirrored that old story from Genesis, of Jacob wrestling an angel only to exit the encounter with a new name, except I keep reading Paradise Lost in hopes of discovering what that name might be.

Ironically, I ended up earning a PhD in early modern British literature, and while I’ve not become a particularly notable or respected scholar of Milton, I at least make up for it with enthusiasm and love. What draws me to Milton is the language—those gorgeous, labyrinthine, serpentine sentences which unspool across dozens of enjambed lines, the chutzpa to promise “Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhyme,” and to then nearly deliver, the cracked aphorisms which court heresy as when Satan declares that it’s “Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven.” Then there is the plot-work of the poem, an epic that begins cinematically in media res with the third of angels who rebelled against God caste into the pits of Hell where they begin to construct heir own infernal parliament and plot their revenge against the authoritarian deity by tempting those new creatures given dominion over Eden.

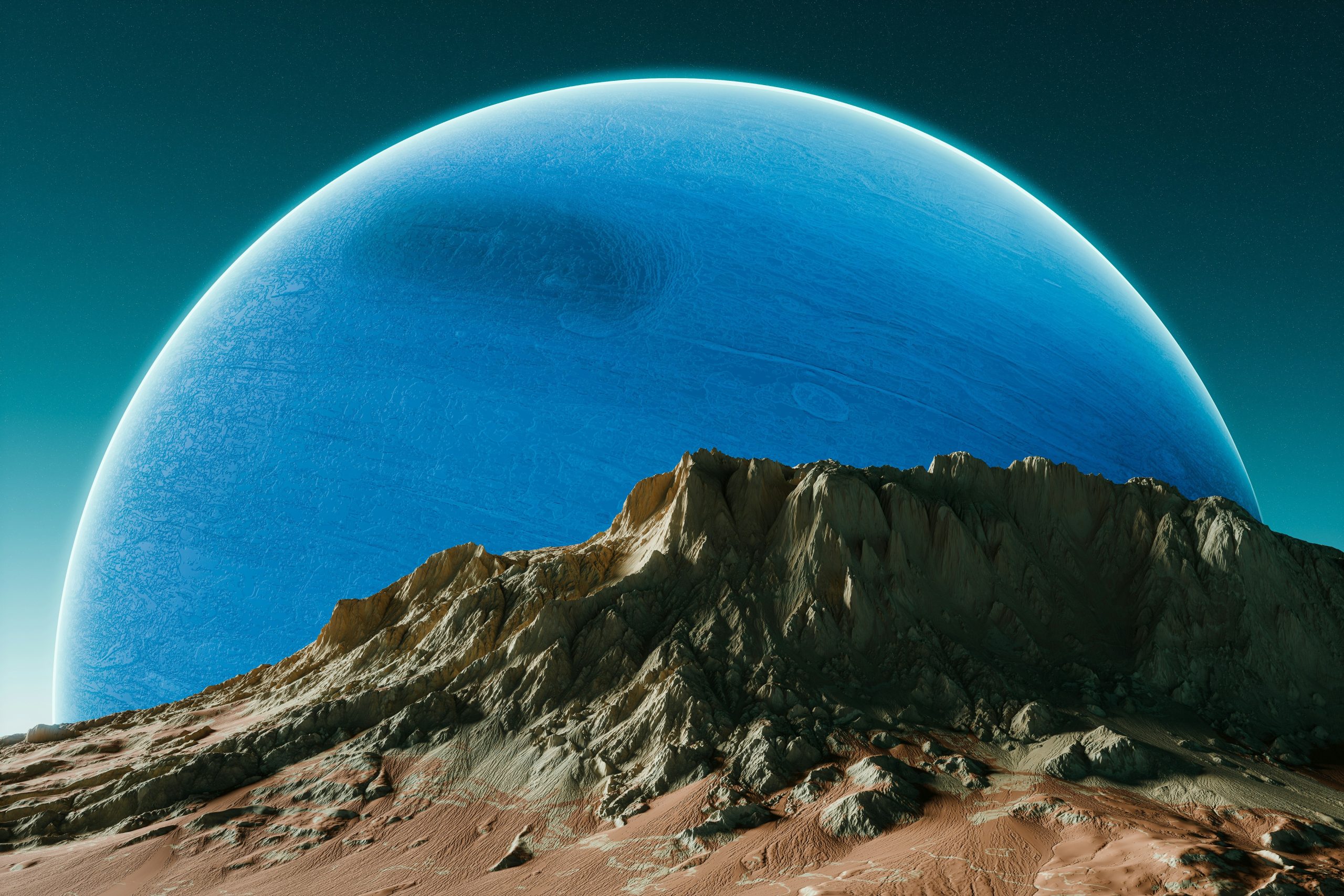

And crucially, there is Milton himself, the failed revolutionary who narrowly avoided execution, composing the blank verse of Paradise Lost in his head at night while his daughters transcribed the poetry in the morning; a conflicting and often unlikable figure who nonetheless encompassed virtually all knowledge of the late Renaissance, and whose Paradise Lost is a polyvocal triumph strung between faith and doubt, orthodoxy and blasphemy, heaven and hell. What I describe in my new book Heaven, Hell and Paradise Lost (hint, hint), is an epic that has nothing which compares to it, not even by Milton. No other book encompasses the maximalist perspective which Milton was somehow able to conjure, ranging from Copernican physics to Lapland witches, New World discoveries to the nature of the Trinity. The author, or narrator, or what-have-you, is somehow a character within it. The reader is somehow a character within it.

And crucially, there is Milton himself, the failed revolutionary who narrowly avoided execution, composing the blank verse of Paradise Lost in his head at night while his daughters transcribed the poetry in the morning; a conflicting and often unlikable figure who nonetheless encompassed virtually all knowledge of the late Renaissance, and whose Paradise Lost is a polyvocal triumph strung between faith and doubt, orthodoxy and blasphemy, heaven and hell. What I describe in my new book Heaven, Hell and Paradise Lost (hint, hint), is an epic that has nothing which compares to it, not even by Milton. No other book encompasses the maximalist perspective which Milton was somehow able to conjure, ranging from Copernican physics to Lapland witches, New World discoveries to the nature of the Trinity. The author, or narrator, or what-have-you, is somehow a character within it. The reader is somehow a character within it.

I’m aware that Milton has, if still firmly entrenched within a kind of Platonic canon, largely disappeared from most peoples’ cultural literacy, even while his influence on English literature is arguably only surpassed by Shakespeare. Because Milton, in his buckled shoes and black coat, comes across as the oldest, deadest, and whitest of old, dead, white authors, it’s easy to turn away from him, even as he was arguably far more radical, revolutionary, and rebellious than might be supposed by those who’ve never had the privilege of encountering him (he, after all, wrote many a pamphlet advocating for cutting off the king’s head, a wish that soon came true). There are reasons to mourn Milton’s eclipse; at the same time it’s also understandable, even if I wished more people were familiar with him. Our lives are rounded abruptly, and the days are finite, so to dedicate yourself to Paradise Lost in a world with so many other pressing concerns, so many other works to read, a veritable universe of art deserving of attention, can seem more an eccentricity than a necessity, the reading of Milton akin to an archaic hobby like soap-making or scrimshaw. But surely these hobbies have their own unique pleasures, their own meditations and contemplations, their own joys, their own beauties. You need not read the following passage from Paradise Lost to be a complete person, but I bet you’ll encounter some beauty in it if you do:

Sweet is the breath of morn, her rising sweet,

With charm of earliest birds; pleasant the sun

When first on this delightful land he spreads

His orient beams on herb, tree, fruit, and flower,

Glist’ring with dew; fragrant the fertile earth

After soft showers; and sweet the coming on

Of grateful ev’ning mild; then silent night

With this her solemn bird and this fair moon,

And these the gems of heaven, her starry train:

But neither breath of morn when she ascends

With charm of earliest birds, nor rising sun

On this delightful land, nor herb, fruit, flower,

Glist’ring with dew, nor fragrance after showers,

Nor grateful ev’ning mild, nor silent night

With this her solemn bird, nor walk by moon

Or glittering starlight, without thee is sweet.

Reading Milton will surely make you far more conversant with the canon; it will help you trace the influence of his work on writers from Melville to Toni Morrison; and it will give you a better understanding of his conflicted seventeenth century, though that’s all of limited utility if you don’t want to do those things. Reading Paradise Lost will not necessarily make you a better sibling, spouse, parent, or citizen; it will not make you a better person. There is a coterie of very boring, tweedy professorial conservatives who will have you believe that if you don’t read things like Milton you’re fundamentally an uneducated buffoon, but I think that’s a predictable and bullshit position. Disrespectful too, because those sort of idolaters of the canon reduce authors like Milton, or Chaucer, or Shakespeare, to mere trivia, to a simple display of cultural capital which trades wisdom for faux-erudition.

The only standard for why you should read something was formulated by one of America’s great inheritors to the Miltonic-prophetic position, the lyrical poet Emily Dickinson, who in an 1870 letter wrote, “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that it is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it.” Why should you read Milton? Not because some tweed-jacketed guy with a podcast tells you to read him, not because I told you to read him. You should read John Milton because he will take your fucking head off. He was the prophet who could proclaim that “The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a heav’n of hell, a hell of heav’n.” Next to that, Milton needs no more justification, for Paradise Lost is enough.