Noah Baumbach’s crackerjack, whizbang adaptation of Don DeLillo’s White Noise is one of the year’s great surprises. Not because Baumbach isn’t a superb writer and director, but because DeLillo’s 1985 novel, a satire of the “endlessly distorted, religious underside of American consumerism,” is one of the great un-filmable books, a rhetorical playground for the most abstract, ludicrous undertakings of this main theme to run amuck.

And yet, Baumbach’s film is an effective parable in its own right, inventing its own visual, sonic, and tonal language (while also featuring much of DeLillo’s prose) to match DeLillo’s exploration of how the human search for meaning is both undertaken and stymied by an increased reliance on material culture.

One of the way it does this is by packing as much stuff as possible into the mise-en-scene; White Noise is endlessly cluttered, packed to the gills with things. If you paused each frame of the film to literally take stock of (or read or count) all the items in its background, you might be squinting in front of your television for a year. It’s like if one of those Dr. Bronner’s Castile soap labels were a movie—each big image is clearly composed of endless tiny little things, all an absurdist carnival of thoughts. In White Noise, the world is a big barrage of matter inundating everyone at all times. The culture is one of “too much”; everything has been taken too far, every product invented, every concept exploited. It is a useless, jumbled world, one built in pursuit of some meaning that has nonetheless remained elusive.

The film, which keeps the novel’s inadvertent setting in the 80s, is about Jack Gladney (Adam Driver), a professor of Hitler Studies who teaches at College-on-the-Hill, a stately institution in the American Midwest. During the day, he lectures to students and confabulates with his colleagues, including his friend Murray Siskind (Don Cheadle), an entertainment professor developing the field of Elvis Studies, and at night he tends to his large family: his wife Babette (Greta Gerwig), and their four children and step-children (Denise, Heinrich, Steffie, and Wilder). They are each other’s fourth marriage and their kids are collected relics of relationships past. But life in their busy home on the outskirts of the college town is pleasant, even though Babette seems to be medicating herself with an off-brand medication for something that Jack can’t figure out.

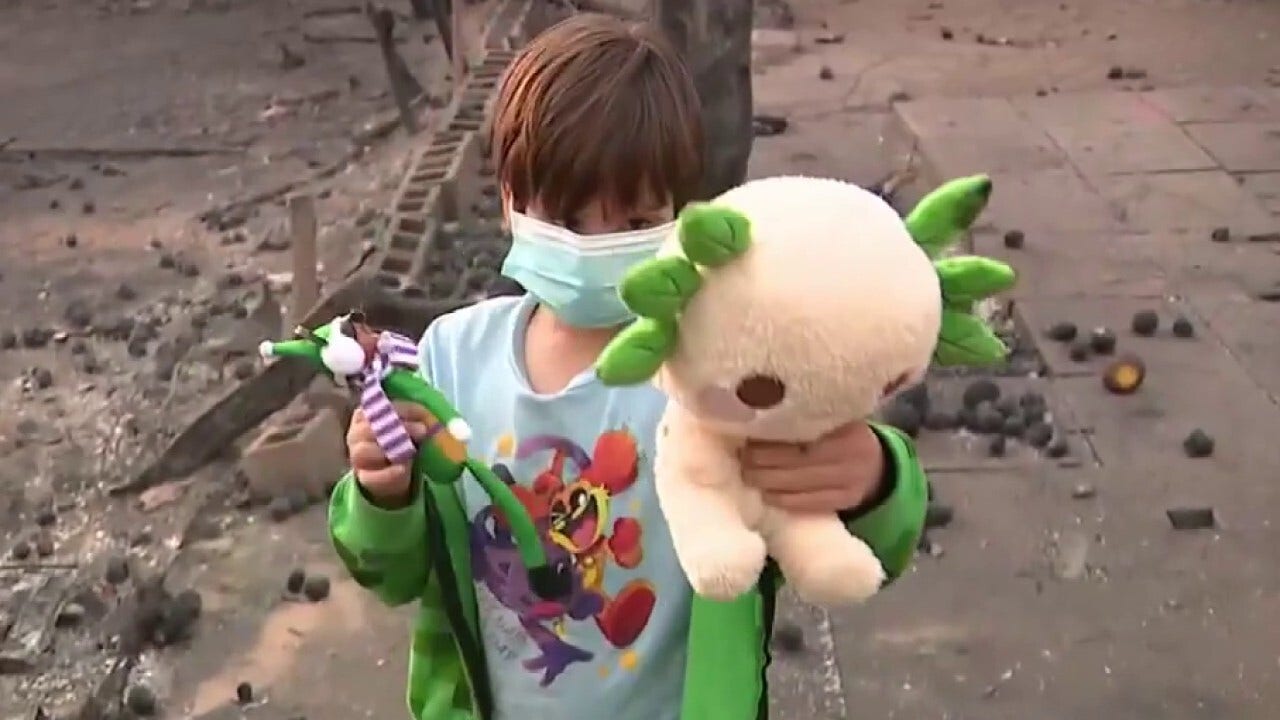

Life goes on, with Jack and Babette enjoying their days together and worrying about the future moment that such bliss will be over. No one in White Noise is good at “being present”—especially after a disaster that comes to be called “the Airborne Toxic Event.” A train crash causes a massive, explosive chemical spill that releases a cloud of noxious gas over the area and everyone is given an evacuation order, causing society to descend into apocalyptic, survivalist chaos. Suddenly, the future is uncertain in an imminent way, and it’s all the Gladneys can do to pull through and try to return to their normal lives.

Baumbach’s script is undaunted by the mass of thematic tackle that White Noise lugs around, packing everything together neatly and patiently. He is a smart and literate filmmaker with a longstanding interest in the pitfalls of over-intellectualism, and proves very adept at braiding together the wackier allegories of DeLillo’s epic with the arresting and even terrifying realities that his characters face without wavering in pace, tone, or orientation.

He also directs some of the best performances of the year: as Jack, a once-confident patriarch amid an overdone and often stupid culture, Driver is the best he’s ever been. Don Cheadle (the most versatile actor working today, I’ll say it) pops up throughout the film with the suddenness of a whack-a-mole spring, appearing as a skewed voice of wisdom, chiming in affirmations of Jack’s worldview and corroborating the human dependence on materialism, and then disappearing again.

Some of the film’s best, funniest performances are by Sam and May Nivola, who play Jack’s kids, Heinrich and Steffie—two loquacious, hyper-formal teenagers who have a clearer handle on modern times than their father. They are detached from the painful anxieties eating up their parents, overly-competent and stilted, nearly robotic in their intellectual, non-emotional engagements with the world. Amid everything else it packs in, White Noise has room to wonder how the next generation will handle everything.

One of the film’s greatest surprises and cinematic wins is the film’s final sequence, which I won’t spoil but will say seems to have been cleverly devised to foil a certain Netflix feature. I mention Netflix because that is the company that produced, and is distributing, White Noise; the film premiered on the film festival circuit and will be opening in select theaters on Christmas day, concurrent with its digital rollout on the streaming service.

If you can, you should see White Noise on the big screen (I mean, look, you should see everything on the big screen, but you definitely shouldn’t miss White Noise on the big screen); it is visually vibrant and fascinating, a crisp and interesting movie that wisely pairs hallmarks of 80s aesthetic culture (primary! colors!) with its more abstract, fatalistic meditations. And it also features an original song from LCD Soundsystem (their first in many years), one that is its own perfect adaptation of both the concerns and energy of White Noise.

Still, it is a good idea to release White Noise at Christmas, a season of intense acquisition, consumption, and expenditure—of attempting to quantify emotion into items and reflect on the passing of time as measured in proximate bodies and the things they have brought or left behind. But I want to be clear that White Noise isn’t a depressing film; it’s enriching in a way its characters might only fantasize about, temporarily evacuating the burdens of time and want, in a knowing manner and with a humorous touch.