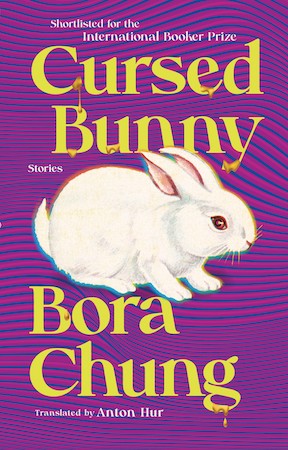

Heads emerge from toilets, constructed from our own debris. Birth control pills lead to pregnancy. Foxes bleed gold. People connect over ghost-watching. In Cursed Bunny, Bora Chung takes us on an unforgettable journey through folkloric caves and modern-day apartments, unearthing the horror and injustice that are engrained in the fabric of human civilization.

I refused to read Cursed Bunny while I was alone. Translated by Anton Hur, the South Korean short story collection melds together speculative fiction, horror, absurdism, folklore, and bitingly-acute observations of contemporary Korean society. Anticipating that I would be too scared if I read it by myself, I sought out public reading spaces. But after finishing the ten stories, I wasn’t certain that reading Cursed Bunny amidst other people provided any comfort. Chung has a way of revealing humanity’s deep cruelty with an absurd twist, tweaking the ordinary and destabilizing the setting around me. She highlights the struggles of the oppressed, using fantastical elements to expose systems of patriarchy, capitalism, and corruption. Hur expertly captures the tone of Chung’s prose, which is deceptively simple; some stories almost sound like the ones you read in childhood—making them all the more haunting.

Chung’s wry, dark humor and passion for activism shone in our Zoom conversation, where we (surprisingly) laughed our way through topics such as the absurdity of misogyny, urban legends, and why a cursed fetish can’t be ugly.

Jaeyon Yoo: What drew you to the fantastic and surreal elements in this collection, especially in addressing the horrors and cruelties of modern society?

Bora Chung: Especially for the minority or the marginalized, I think the fantastic or the unreal is a better approach for telling their stories. It will vary, according to people’s experiences, but if you try to criticize current society and the state of things in a realistic manner, it runs the risk of turning into a statement—not fiction. And the situation is absurd and illogical [already]. Why should a certain type of human be considered “lesser” than another, because this first type of human has functioning ovaries and a uterus? There’s no logic to it. When you’re confronted with this type of absurdity, it’s very natural to respond with absurd, illogical, and unreal narratives. That’s what fits best.

I never learned creative writing, so I learned everything I know about writing from reading other people’s words. I studied Slavic literature in graduate school, [which] has a very rich tradition of blending genres and defying the order between the fantastic and the real. Do you know Nikolai Gogol’s The Overcoat? The poor guy becomes a ghost to get the overcoat. And in “The Nose,” a man sees his nose in a uniform that is a higher rank than himself. How does a nose wear a uniform? This is considered one of the canonical works in Russian literature. It’s ridiculous! But this is one of the best writers of the Russian literary tradition. In every single Russian literature class, you read him and people fall in love with him. This opened my eyes to the fact that you can incorporate the fantastic and still make really good stories, that people will enjoy it. It doesn’t have to be realistic. I was fascinated, and thought, “If they can do it, maybe I can do it. I might never be as good as Dostoyevsky, but a girl can dream!”

JY: The story that resonated with me the most was “The Embodiment,” probably because I’ve had my share of traumatizing experiences at a Seoul gynecologist. Your fiction made me think about body as a process and a verb, one that is constantly fragmented and broken… Can you talk more about your depictions of the female body?

BC: The first part of “The Embodiment” is what I went through. When I first went to the U.S. to study, you say in Korean that you “change waters.” You’re trying to adjust to the new environment, and you have to go through this adjustment period. When I came back to Korea, my period wouldn’t stop for two weeks. I was 28 and unmarried at the time. I told my mom that I needed to go see the gynecologist. And the first thing she said was, “You’re not going to a gynecologist yourself!” If I had broken a finger, nobody would have told me I could not go see a doctor because I was unmarried. My mom eventually went with me to the gynecologist. I was not eight or 18-years-old—I was 28. By the way, my mom’s a dentist. She’s a highly educated woman and a very exceptional 1% of her generation. But the conventions, traditions, and ideology she grew up with was so strong that it prevented her from going beyond that and seeing it from a medical point of view. Around that same time, I discovered the Korean verb, “to body.” I really liked that verb. It’s an outdated term. Koreans don’t use that particular word anymore for that meaning, but it’s in the dictionary. I thought, this fits my experience perfectly. Because menstruation is something you do with your body; it’s a sign that one’s body is functioning, or a sign that one’s body is not functioning. And then all the weird guys that appear later in the story, some of them are actually from my aunts’ and mom’s stories—the weirdos that they encountered during their younger years. The guy that recites Shakespeare? That guy really existed. There are so many weird people in the world, and that makes me hyper-realistic. I wanted to be an absurdist, but there are so many people that are weirder than my imagination.

JY: Absolutely—the most horrifying or absurd moments seem to be the ones pulled from reality! You’ve talked about the influence of Slavic literature, but another reference I picked up was folklore.

BC: I think it’s common in every culture to tell children folk tales. I grew up reading a lot of folk tales, and I still love folklore and urban legends. Back in the ’70s and ’80s in Korea, there was this boom of children’s books that were 50 or 100 volumes. Usually, middle-aged women would knock on your door and try to sell you this multiple-volume children’s book series. It was a status symbol. My mom bought me this 100-volume series, and it had all kinds of fairy tales. Arabian, Japanese, European, Chinese folk tales—I loved them all. I also love Samguk yosa and Samguk sagi, two of the oldest Korean history books. They fuse seemingly realistic historic events with most certainly unrealistic events and mythical creatures. There are a lot of dragons in Samguk yosa. People are obsessed with dragons—there are dragons in every single entry. When something important happens, there has to be a dragon. There are so many various forms of folktale, and they are wild and very creative—unimaginatively imaginative.

[As for] urban legends, they’re still alive and kicking. I love Japanese urban legends—they have so many good horror stories. It constantly reminds us that what we think we know is not the entire world. Human beings are so small. We only have five senses. Some people claim to have a sixth, but it’s not empirically provable. We are so limited; there is a whole universe out there that we will never understand or never feel in a concrete way. It’s a mistake to be arrogant and think, “I am the human being. I am the superior being and I know everything.” I think there is an element of the unknown and horror living with us all the time. Urban legends remind us, in a very modern and mundane way, that the unknown is with us. I like that feeling, that there is something more to this world than what we see and hear. It’s scary, but it’s also very interesting—there will be something more than what I know and what I have now. It’s a grand statement, but that’s what makes life worth living: there will always be something more.

JY: I was really struck by was this boundary—and blurring of that boundary—between the animal and the human. (Although there are no dragons in your book.) I came away questioning what we, as a society, define as “natural.” Could you talk more about these themes of the natural/feral, juxtaposed against the human/civilized?

BC: That concept is very cultural, and it is probably very different in the West than in Asia. And it will depend on specific cultures in Asia as well—Asia is very large! As I said, I love folklore. I saw so many similarities in Slavic history books and Samguk sagi and Samguk yosa, for example. If you go back to the roughly 13th century or before, people live with mythical creatures, become mythical creatures. And these are history books! They record these fantastical phenomena and are just living among other non-human beings. That was considered natural. That is something very important, and we lost it. I can see why we lost it, too. Nature is not good to humans. If we lived in a feral environment, I would have died in three seconds. Human beings are so weak in wildlife and nature, so we have to protect ourselves with this bubble of civilization, but that is not because we’re superior. It’s because we’re so weak.

JY: And yet the society you depict in Cursed Bunny is one filled with violence and revenge; it doesn’t necessarily protect us, either. Ultimately, I thought your collection meditated on what it means to survive in our modern-day society, and how to find meaning within survival. Do you have thoughts on the connection between societal violence, survival, and literature?

BC: These stories are now rather old, and my perspective has changed a lot, especially since the Sewol Ferry disaster. I began to protest after that. Up until 2014, I was your typical couch potato intellectual who criticized society but did nothing. But when children died in front of me, and the TV stations broadcasted everything real-time, for three days, how people died and were stuck on the boat for three days—it was pure hell. The stories in Cursed Bunny are mostly from before 2014, so they are more abstract and vaguely fantastical. I didn’t know how to formulate my opinion on society. After [the Sewol Ferry disaster], I’m like, “Go protest!” and “I’m gonna kill you all!” [Laughs.] No, not everyone—I love my readers. I want to kill the bad guys. I think that is consistent in all of my work. I want the bad guys to die. That is my response to society and violence.

Urban legends remind us, in a very modern and mundane way, that the unknown is with us.

When I was sitting at home and thinking about fantastical stories, I didn’t really know how [society’s] structures worked. When I went to all these protests and met people, the one thing I experienced was solidarity. With the Sewol Ferry Disaster, the entire world came to sign the petition. They all came and listened to us and signed the petition, because they understood people should not die that way. Just a few days ago, the workers from SsangYong Motors won at the Supreme Court. It was ruled that the workers had the right to defend themselves. It took them 13 years and 33 people’s lives, but they won. And the people from SsangYong Motors came to the Sewol protest site and sat with us. We go to their protests, too. That’s where I met what became my entire world right now. I think my perspective has changed a lot, from “I want the bad guys to die” to “I love these people, and I want other people to die.”

I guess this solidarity ties back to what I just said earlier, about there being something more to life [beyond the human senses]. With my SsangYong Motors men, I was prepared to cry with them when we all went to the Supreme Court. They came out crying. But then they were glad to see me, which means something good happened. I was so terrified—all the people who went there in solidarity were terrified, and then we were all very pleasantly shocked. We cannot know the future. I guess change is possible. People suck, but they can change and suck less.

JY: Speaking of protests, could you talk about how you address capitalism, which I see as another theme in your writing?

BC: I can’t really say it’s all purely “capitalism” that I address. Capitalism is doing a lot of horrible things, but there are always some other elements that make things worse. In “Cursed Bunny,” it was corporations that colluded with power, dictatorship and totalitarianism. In “Home Sweet Home,” it’s patriarchy, that part of Korean culture that is very oppressive to young women specifically. So, it’s patriarchy, in the worst form, with capitalism. There is always some other thing.

JY: And, as you said, you turned to fiction as a way to kill these bad guys, creating this intersectionally-terrifying world that’s not so different from reality.

BC: But in reality, bad guys won’t die. Why won’t they die?

JY: In that sense, the world of Cursed Bunny (where the bad guys die) is less scary than reality!

BC: I guess…

JY: In “Cursed Bunny,” the cursed fetish-maker is obsessed with crafting something pretty—and there’s an alluring element to your prose, even as the material it depicts is often horrifying or twisted. Do you see the horrific and beautiful as intertwined?

BC: I actually never thought about it that way. I like pretty things. When I was writing “Cursed Bunny,” I belonged to this writing group called Mirror Zine. At the end of 2015, we were talking about what to write for the new year. Somebody suggested the Asian Zodiac [with 12 animals]. I was late. The fast people took all the glamorous animals—like the dragon, the tiger. The second people took all the familiar animals—the dog, the rooster, the horse. When I read the web board, there were only the bunny and the sheep left. I know nothing about sheep. We had two bunnies when I was in elementary school, and I have a very vague memory of taking care of bunnies. This was better than nothing, so I took the bunnies. Bunnies are pretty, but they are the weakest animals in the entire food chain. They don’t have any claws or sharp teeth—they have nothing to defend themselves with. I thought, “I’ll need to make them scary. If I go with the fuzzy, cute bunny, it’s going to be ordinary and boring.” But I wanted to keep the cute element, and then make them scary. That was my thought process. I wasn’t really thinking about the theme of beauty. I just wanted to write scary, fuzzy bunnies. And if cursed fetishes were ugly, nobody would touch the cursed fetish and it’s going to fail as a fetish.

JY: Something I’m struck by in your writing process is its logic! You think through the logical steps, such as, “Would I touch an ugly fetish? No.”

BC: I write about weird things, so the underlying thinking and emotion have to be understandable, come naturally. Otherwise, it will be an incomprehensible story.

JY: Do you have anything else you’d like to share with Anglophone readers of Cursed Bunny?

BC: You can go to the bathroom and you won’t die. There are no bunny curse traditions in Korea. Contraceptive pills do not make you pregnant. Do not give this book to your children.

Human beings are so weak in wildlife and nature, so we have to protect ourselves with this bubble of civilization.

In an interview I did with the BBC, the anchor very seriously asked me about the curse tradition of using bunnies in Korea. I told her that I lied: that everything is made up, and there is no curse tradition with bunnies. We do have curse traditions, but we use dolls. We don’t use live or magic or killer bunnies. She seemed very disappointed. I apologized profusely, but there is no such tradition. This made me think that people like these folk tale elements, and the specificity of my stories is something new and interesting. I specifically made sure that my stories don’t contain anything really traditionally shamanistic. Because people might try it at home!

JY: I will say, I was very careful for a few days after reading around toilets and bunnies…

BC: I’m so sorry! People complained to me a lot that they can’t go to the bathroom after reading “The Head.” Nothing will happen, it’s all made-up. I’m a professional liar and I lie very well, but these are all lies.

JY: Do you have an object you’d choose as your cursed fetish, if you weren’t last in your writing group and stuck with the bunny?

BC: Now, I kind of like the bunny. I do like cats. I want a cat—actually, I want to be a cat. [Our interview concludes with a cat show-and-tell, in which Bora meets my cat.]