Before the video is over, I’m snickering and sending it to my TikTok-addicted best friend. He’s a New York wine exec whose only experience with poetry is at my readings. Until now. Onscreen, a manicured hand opens a slim book against the backdrop of rumpled bed sheets—then a perky woman’s voice starts reading:

you deserve to be loved without condition. you are enough, without

trying harder. without learning new things, without accomplishments.

without success. without getting bigger or smaller. without getting

smarter. without improvements. without changing anything at all.

you are enough, just as you are.

The poem comes from Michaela Angemeer, aka Michaela Poetry, whose page I discovered in an attempt to teach myself TikTok. She has 774K followers, and in October 2022, she posted a video about how she had recently hit $1 million in sales from self-publishing five poetry collections. The themes of her work are summed up in her one sentence bio: “Michaela Angemeer is a Canadian poet and author who’s passionate about sharing her self-love journey.” Self-love, heartbreak, grief—all tenets of the TikTok poets. I joined TikTok last September with every intention of playing the game and selling my own poetry collection. Youth is a mix of film photos and typewritten poems—designed and published by myself—about the angsty 20s and emerging from their haze. From the outside, it seemed an easy fit for BookTok, and after a lifetime abstaining from social media, it was time for my symmetrical bone structure and Gen-Z haircut to shine. Surely, learning to self-promote couldn’t be harder or more demoralizing than the last decade I’d spent writing, getting rejected, and persevering in making my art.

Yet the more time I spent on the platform, the more I encountered poems such as this one from Whitney Hanson (1.8 million followers):

ice cream with my ex

“you’ll always have a soft spot for me,” she teased

“that’s not funny,” i replied, holding back tears from my eyes and knowing she was right

Like many poems on the platform, this piece reads less like poetry and more like a spewed text message. Even as I forced myself to ignore Hanson’s irregular punctuation, there is nothing below the surface. The poem is telling me how to feel, telling me to miss my ex, but when I read it, I don’t. Its comments, however, disagree: “hope u hav an amazing day and know ur legit amazing and changed so many ppls lives (including mine) using ur words <3;” “crying throwing up”; “you inspire me to be here thank you.” The simplicity of these poems allows them to be relatable, and the way to respond to their emotion is to vomit yours in turn.

Far from TikTok, the most recent poetry collection I read that inspired me to be somewhere was frank: sonnets by Diane Seuss. And while crying and throwing up is not far from how I felt while reading it, I was moved by its sheer beauty–by the way Seuss’s words play and pour across the page. The form, as much as the content, of these poems pulls at my heart. It’s true that the rawness of these stories could fit into the tropes of TikTok. Take the opening of Seuss’s confessional:

by Diane Seuss. And while crying and throwing up is not far from how I felt while reading it, I was moved by its sheer beauty–by the way Seuss’s words play and pour across the page. The form, as much as the content, of these poems pulls at my heart. It’s true that the rawness of these stories could fit into the tropes of TikTok. Take the opening of Seuss’s confessional:

I aborted two daughters, how do I know they were girls,

a mother knows, at least one daughter, maybe one

daughter and a son, will it hurt I asked the pre-abortion

lady and she said, her eyes were so level, I haven’t been

stupid enough to need to find out, cruel but she was right

I was and am stupid, please no politics, I’ve never gotten

over it, no I don’t regret it, two girls with a stupid penniless

mother…

These lines are also rich with enjambement, repetition, and a rushing momentum. But although frank: sonnets won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize and other prestigious awards, and Seuss has a not-unimpressive 13K followers on Twitter, and is in my humble opinion a poetry rockstar, when I search her name on TikTok there are a paltry smattering of results: a librarian holding a copy of frank: sonnets; a woman drinking Gatorade then reciting the above poem. The most popular video has 3,000 views; Hanson’s average in the 100,000s.

Seuss holds a BA from Kalamazoo College and is as self-taught as most poets come. In an interview on the podcast Breaking Form, she speaks about how the quality of her work is indebted to decades of teaching at her alma mater. “I wasn’t educated. I don’t have an MFA, I don’t have a PhD in literature. I had to teach myself pretty much everything in order to teach them.” It’s surely Seuss’s years of reading, writing, and revising that allow her poems to whirl so magnificently. If Seuss is self-taught, then the poets of TikTok, who make no mention of degrees or studies, are untaught. Seuss, for instance, describes her writing process as “balancing between the kind of commotion that comes in and the excitement of the rant, and the knowledge base that says, you know, break the fucking line.” In my months on TikTok, none of the poets seemed concerned about where to break the line. They may not even know there are lines to be broken.

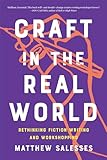

In recent years, the concept of craft in writing has been given its own close read. Here is one definition that Matthew Salesses gives in his revelatory book, Craft and The Real World : “Craft is about who has the power to write stories, what stories are historicized and who historicizes them, who gets to write literature and who folklore, whose writing is important and to whom, in what context.” In this way, the TikTok poets’ defiance of craft could be allowing new voices to be heard and to become important. They could be spurning the white patriarchy, which told us what to write and who could write it–or as Seuss says in her interview, “When people used to say, ‘I’m really into craft’…It sounded like ‘wear a bra,’ and ‘keep your legs together.’” Certainly, it’s time to move past being told how to dress tidily, much less write a poem that way.

: “Craft is about who has the power to write stories, what stories are historicized and who historicizes them, who gets to write literature and who folklore, whose writing is important and to whom, in what context.” In this way, the TikTok poets’ defiance of craft could be allowing new voices to be heard and to become important. They could be spurning the white patriarchy, which told us what to write and who could write it–or as Seuss says in her interview, “When people used to say, ‘I’m really into craft’…It sounded like ‘wear a bra,’ and ‘keep your legs together.’” Certainly, it’s time to move past being told how to dress tidily, much less write a poem that way.

Yet there is a difference between throwing on an audacious outfit and paying no heed to your clothing at all. When I teach, my approach to craft centers on getting writers to vocalize their artistic decisions. Rather than saying a poem is “well written” or “needs work,” we ask students questions: Why did they leave out punctuation? Why is this word repeated? What are their decisions behind form? The more the writers are able to articulate their decisions, the more they invest in their own revision process and make intentional art.

Lately, I’ve been skewing the idea of craft toward craftsmanship (while setting aside the gender inherent to that word). By regarding my poems as, say, pieces of woodwork, I gather my ideas then I assemble them with various tools. When I’m revising, I imagine sanding my poems down—using a finer grit paper on each pass. TikTok is not a platform for close reading or admiring craftsmanship. Sometimes the poets read their work with no accompanying text, not in the style of spoken word, but talking to the camera without acknowledging that their words have form. These poems are particle board and mass-produced, and as I get in close and try to pick the lines apart as we do in my classes, there are no fine details to admire.

In an interview with Reader’s Digest, Hanson describes putting together her first collection, saying, “I just started writing poems in the Notes app on my phone…Then I started compiling them, and it turned into a book! And then I just threw it out there into the world.” While I would never discourage anyone from writing as a means of therapy, if one of my students described their artistic process in this way, I would wonder why they were sharing their work. What is writing without intention, revision, and care?

Yet Hanson’s tactic of throwing her work out into the world has clearly paid off. In early May, she posted a video announcing that her originally self-published debut, Home , was being rereleased by Penguin Publishing Group. Her green eyes close to the camera, Hanson confessed that she has always fantasized about being a New York Times bestseller. Would her followers make her dream come true? Just as craft once defined whose writing is important, traditional publishers have been denounced as gatekeepers. But large publishing houses are no longer acquiring works based on the white patriarchal definition of craft—they’re looking for marketability. They’re looking for authors who have social media followings and books that will sell on TikTok.

, was being rereleased by Penguin Publishing Group. Her green eyes close to the camera, Hanson confessed that she has always fantasized about being a New York Times bestseller. Would her followers make her dream come true? Just as craft once defined whose writing is important, traditional publishers have been denounced as gatekeepers. But large publishing houses are no longer acquiring works based on the white patriarchal definition of craft—they’re looking for marketability. They’re looking for authors who have social media followings and books that will sell on TikTok.

In an aptly titled report, “Ten Awful Truths About Book Publishing,” Steven Piersanti of Berrett-Koehler Publishing puts numbers on the influx of self-published books and the dramatic drop in average print sales of all books. While there were 2.3 million books self-published in the US in 2021, the average book, across all categories, sold less than 300 print copies over its lifetime. The report calls the market saturated—most books are selling only to authors’ communities and are advertised by the authors themselves. Piersanti’s emotionally detached piece finishes with strategies for responding to these truths: “Master new digital channels for sales, marketing, and community building”; “Front-load the main ideas in books and keep books short.” In other words, emulate the writers who have made it on social media.

As of this writing, Home is not yet a New York Times bestseller, though the bestseller lists at the Times and Publisher’s Weekly are increasingly populated by Instagram poets like Rupi Kaur, Kate Baer, and Yung Pueblo. The only Seuss that ever appears on them is Dr. Seuss.

*

My most viewed video on TikTok, “Three Ways to Start a Poem,” currently has 19,000 views. I offer the openings of three of my poems from Youth as possible ways to start a piece. The instructions I give are more direct and reductive than any I would present to my students. The video is one minute long, and according to the analytics, most people watch the first 11 seconds. In the 10 months since I joined the platform, I’ve amassed over 2,000 likes and over 200 followers, but have yet to see a significant increase in traffic on my website. I haven’t sold a single copy of my collection, and lately, I don’t care.

In the morning, I leave my phone at home and write in the library. In the afternoons, I teach, edit, and study to be a meditation teacher. There are no notifications on my computer; there isn’t even a clock. I write poems in my head, far from my phone, while I walk in nature. I perform them at open mics where the vulnerability of a live audience is so much more visceral and meaningful than the anonymous void of the internet.

In my early months on TikTok, I was a diligent student. I took classes, read articles, and watched videos of other poets on the platform. I was advised to post at least once a day—videos of the same aesthetic, the same angle, the same idea; I could cut my poems into snippets or write shorter ones. If I was to be a TikTok poet, I would need to write often and without contemplation or revision. Success is determined by an algorithm, and the more formulaic my work, the more followers I would have.

I haven’t deleted my account—being on TikTok puts too many readers and book buyers at my literal fingertips. TikTok’s promise is so much more tantalizing than my last decade of toil: a BA in literature from a liberal arts college; mentorship from a successful author; stints working in bookstores, teaching, and editing; slowly getting published; poetry performances and my self-published chapbook; a novella released by an independent press; and now, querying agents for my second novel. All of this work hasn’t guaranteed a path to publication and financial security any more directly than by an app on my phone.

*

In May, Whitney Hanson posted a photo overlaid with text:

Sitting in an airport thinking about when I was heartbroken and feeling so lost in life I wrote a book about it. Now, because of you, writing is my full time job and I’m flying to France to work on a really amazing project. Life is crazy. Thank you for all the love <3

How long will writing be Hanson’s full-time job, and what does that entail? Will she study writing and read other poetry? Is this the start of a fruitful career or merely a peak before distraction and depression? Where else does heavy smartphone use lead? I think of Seuss’s exploration of immorality in her incandescent ending to frank: sonnets, “[I hope when it happens]”:

…I had kissed lips that kissed Frank’s lips though not

for me a willing kiss I willingly kissed lips that kissed Howard’s deathbed lips

I happily kissed lips that kissed Basquiat’s lips I know a man who said

he kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed Whitman’s

lips who will say of me I kissed her who will say of me I kissed someone who kissed

her or I kissed someone who kissed someone who kissed someone who kissed her.

Who will have kissed the poets of TikTok? And who will care?