In her recent essay “Anxiety and Responsibility: What Stories Can Come From Our Current Moment,” Clare Pollard almost wholly encapsulates a prevailing literary ethos: that the primary function of social novels is social change, that social change lends fiction real-world utility, that its real-world utility makes fiction a craft, that this craft requires labor, and that this labor includes a responsibility to historical accuracy and progressive politics.

If it sounds like I’m about to get up on my high horse, that’s because I am.

Not only do writers of fiction bear no such albatross, but the misplaced anxiety that they do imposes undue artistic limits on authors that displace and undermine the actual responsibilities novelists do have: aesthetically to beauty, and ethically to truth.

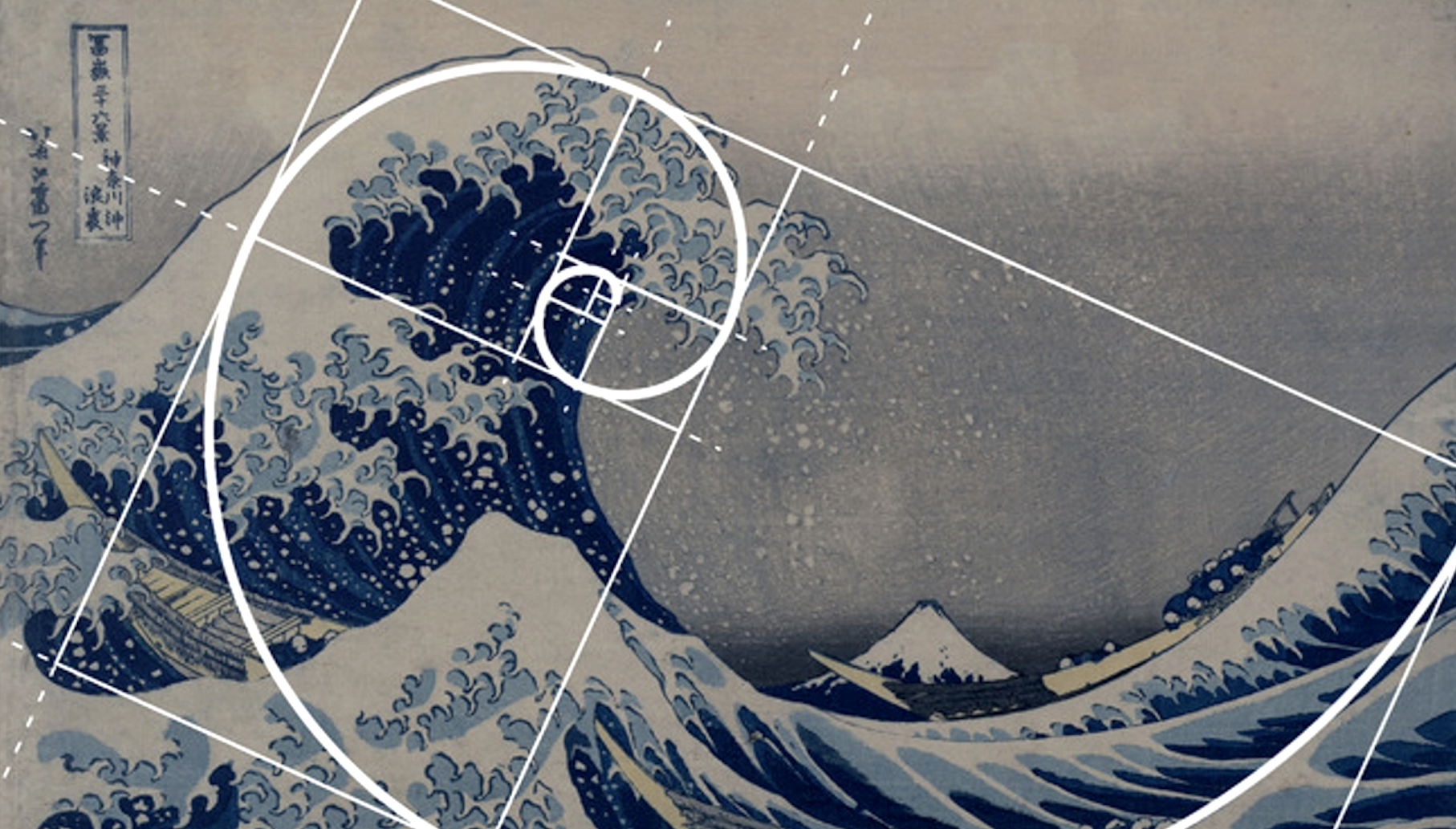

Note novelistic truth is distinct from fact, as is similarity from sameness. It’s at the precipice of these nuances, from which social media tends to push us in avalanchesque collapse, that historico-political demands of fiction become demonstrably illogical. Consider Pollard’s thesis: “Any contemporary novel that doesn’t acknowledge the pandemic is just alt-history or fantasy.” Let me be the first to agree that mimetic fiction and alt-history share a remarkably similar set of seductive narrative benefits. However, that they both spuriously capture the emotional texture of reality does not make them the same thing.

To conflate any novel with alt-history ignores the crucial difference in their representative contexts: novels represent fiction as fiction, while alt-history represents fiction as fact. Insofar as a contemporary novel begins to diverge from reality, it becomes less realistic, but not any more or less fictive. Regardless of where a work sits on the mimetic continuum, from autofiction to fantasy, in its most successful manifestations, fiction illuminates truth by way of transparent fabrication. Alt-history’s goal is more or less the diametric opposite.

It follows that fiction and history proper are discrete as well. It is not novelists who owe a responsibility to history then, but journalists and historians and citizens in their real-world capacities. Insofar as living novelists are citizens and human beings, they have historico-political responsibilities in the real world qua citizens—but not qua authors, and certainly not in fiction.

Why would any novelist, let alone the lion’s share of contemporary writers, want to foist such patently unwarranted restrictions onto their art? I have a few theories. The first is genuine feeling—perhaps you’ll recall it as that place from which all bad poetry springs. The second is guilt. And the third is sheer literary survival in the current moment.

*

Genuine Feeling

When Pollard asserts that “To write nature poetry without the thrum of climate disaster in the background is in itself a form of denial and complicity,” I have no doubt it stems from an earnest fear for our planet, but that doesn’t make it any less ridiculous. So many foreboding climate novels have been written at this point that “Cli-Fi” has become a full-on genre. If writers of fiction could solve the problem of climate change, I can promise you that the problem would already be solved.

In my most cynical moments, I wonder if the return to literary moralism isn’t an evolutionary tactic of publishing’s extant power structures.

This is neither to say that fiction can’t influence reality (it can and does) nor that the choice to embrace historico-political constraints can’t be a marvelous one, but simply that literature’s potential for influence is not derived from a moral purity test—it is derived from aesthetic success. Said another way: novels can only influence the real world if they captivate, and beauty is the necessary and sufficient condition to captivation. Historico-political constraints are optional. The best writers who choose to use them actually understand this; indeed, it is why they are the best. Think of that ubiquitous ad for Masterclass, where Margaret Atwood says: “People are always coming up with new theories of the novel, but the main rule is: hold my attention.”

The Handmaid’s Tale is a successful novel not because it is anti-fascist and supports reproductive justice, but because it is beautifully, dare I say stylishly written. From the first paragraph we get lines like “the music lingered, a palimpsest of un-heard sound.” This is why I want to read on.

The intrinsic motivation of beauty and its ability to rouse strong feelings should not be confused with extrinsic social obligation and the well-intentioned yet pernicious idea that literature “builds empathy” and should be digested like some kind of moral medicine. Set aside that empathy isn’t even necessarily a social good—great art justifies itself. No wonder people have turned to television.

*

Guilt

A great irony of the moral-medicine view of literature is that it largely comes from an egoic place. Specifically: the queasy sense that if art is not useful then it is a luxury—a privilege—and artists themselves an unflatteringly élite part of the political problem. It is easy to see why a progressive author, anxious to make the world more equitable, would prefer to dub fiction a craft, a word so suggestive of the working classes; of, like, earthy pottery and Jesus-style carpentry; of the egalitarian idea that diligent labor, not innate aptitude, is the primary driver of literary achievement. Art is snobby and highfalutin; craft is down-to-earth, community-focused. Art is a champagne cocktail; craft just a beer.

MFA programs are often blamed for the confluence of literary style into a bleak row of Bud Lights over the past twenty years, but I think the broader ascendance of fiction-as-craft has more to do with it. Craft helps bridge the cognitive dissonance between collectivist values and individual glory, quelling historico-political guilt, but distracting from the actual ethical questions pertinent to fiction.

Namely: plagiarism, to which this guilt stridently upholds reactions as bizarre as originalist interpretations of the Constitution. The recent impassioned Twitter defense of a writer caught plagiarizing an article on plagiarism in a piece about why she plagiarized her debut novel is a particularly egregious example.

Unfortunately, novels crafted to avoid historico-political guilt—and, increasingly, accusation—also tend to be even less aesthetically successful than those springing from genuine feeling alone. When the raison d’être of a novel is to signal the author’s real-world virtue, this cannot help but become visible to its readers, disrupting not only the immersive experience of fiction but the very effects of mimesis that mandates like “acknowledge the pandemic” seem designed to protect.

We’re back to the lost nuance between fact and novelistic truth here, but with the added problem that the whole craft-and-labor thing isn’t factual either. As debut novelist Sarah Thankam Mathews put it recently, paraphrasing Philip Roth: “writing is not hard work, babe; coal mining, that’s hard work.” I’ll take this a step further and argue that writing is a privilege—one that papering over squanders without in any way eliminating.

*

Sheer Literary Survival

So craft suggests anyone can labor into authorship, more people write and query and submit, literary supply further outpaces demand, and traditional publishing grows ever more fiercely competitive. You can see why, in such an environment, even talented novelists would be incentivized to favor historico-political disqualifications they themselves surmount. Nothing ignites passionate support like the nexus of moral belief and personal benefit. The logic here often rests on another failure of nuance though, conflating the privilege of writing with privileged identities, élite talent with entrenched power, to promote progressive fiction as some kind of real-world victory for marginalized people when it’s not.

A great irony of the moral-medicine view of literature is that it largely comes from an egoic place.

If the role of talent in writing fiction makes our enterprise elitist, it is no more so than, say, playing in the NBA. While there are certain fundamentals that can be taught and learned, effort alone won’t turn you into Toni Morrison any more than it will make you Steph Curry. Great novelists also have a gift, harder to define but every bit as unteachable as height, and perhaps even rarer. Literary aptitude is obviously less immediately visible, and equality of opportunity a genuine concern—but not one abated by progressive fiction any more than climate change.

In my most cynical moments, I wonder if the return to literary moralism isn’t an evolutionary tactic of publishing’s extant power structures, substituting real-world issues of employment and portfolio identity representation—which do matter—with equitable representation within individual works of art—which does not. This might explain the recent litany of mediocre novels by palpably anxious authors that read like they’re trying to win oppressed-identity bingo, while real-world diversity in publishing continues to flounder.

*

Pollard ends her essay with the admission that even she is beginning to tire of Cli-Fi, and wonders vaguely how novelists should proceed—whether it’s even possible. I assure you that it is, and have put together a few specific tips for writing aesthetic fiction. Consider them an invitation to join me on my high horse. The view is superb.

1.

Success generally rests on disarming the very cognitive defense mechanisms designed to protect one’s fragile psyche.

2.

The most unbelievable people make for the most believable characters.

3.

When you write about writing, the bar is higher.

4.

“The great novelists reveal the imitative nature of desire.” –René Girard

5.

Study the great novels you desire to imitate; a classroom may be helpful, but is certainly not required.

6.

Steal a little bit from everyone and you’ll never be a plagiarist.

7.

Traditional novels are often the most original (see T.S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent”).

8.

“When information becomes free and universally accessible, voluminous research for a novel is devalued along with it.” –Jonathan Franzen

9.

Twitter can be helpful in marketing a book, but it is usually not helpful in writing one.

10.

“The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.” –Oscar Wilde