“Palcoholics” by Jake Maynard

My bro Brian used to tell me he loved me. Throughout our twenties he’d say it every year or two, unprovoked, unexpected, and always at night—just like a leopard attack. Brian still lives in our hometown, so for years when I’d visit my family, we’d get drunk together. We met at the only bar in town, The American Legion, or at his house, which had once been a funeral home and still looks like one. We’d drink and smoke and drive back roads to country bars or rendezvous with some friends at someone’s trailer. Brian backed his beer with Jameson or blackberry brandy, and everything got hazy, fast.

Eventually, after all the stories were retold and the town gossip aired, we’d go outside for a smoke. He’d say, “I love you, brother” in a voice that sounded a little like Hulk Hogan. I never saw it coming. Most times I’d choke out the only correct response, but once in a while, my words failed me, and I’d find myself saying “thanks” or “same” or “and you too, good sir,” as if male insecurity had suddenly given me a top hat.

The problem was twofold: I didn’t know what he meant, and I didn’t know what I felt. There was something inside, a nearly gene-deep loyalty—the sad community of practice that bros forge over slurred nights. But the feeling felt burdened with nostalgia, a Polaroid stained with spilled beer. Maybe that was it. Maybe it was the drinking. That’s what I’ve been trying to understand.

We grew up together in the 90s in a tiny logging town of 700 people in the most rural part of Pennsylvania. Our elementary class had nine students. As my family lore goes, he followed me home from kindergarten (my first time, his second) and never left. His grandfather was a barfly who finally quit drinking and obsessively carved wooden birds in his basement, a tactic to help him stay sober. His dad was a hard-working, rakish alcoholic who looked like a redneck version of John Hamm. His dad’s brother had been killed twenty years earlier in an accident with a homemade hang-glider that Brian’s dad was pulling through the air with a pickup truck. The field where he died was left to grow wild.

My dad was a drinker, too, a proud left-leaning factory worker who gave up partying when my sisters and I were small. He turned to sitting on the porch, listening to Led Zeppelin and nursing his arthritis with glasses of sour wine he made in the basement. There were gallons of the stuff, and it made me more popular than I had any right being among the redneck kids in my hometown.

His dad was a hard-working, rakish alcoholic who looked like a redneck version of John Hamm.

In the year 2000, When I was twelve and Brian was thirteen, we rode our bikes to our first real party, in some woods behind a big red barn. I wore a Tommy Hilfiger t-shirt from the Goodwill and we sprayed ourselves with Christmas stocking cologne like it could keep away bugs. We drank Mickey’s Grenades with high school kids and creepy dudes in their twenties who hovered over the girls that were only a little older than us. We smashed bottles against trees and pocketed the caps as evidence. Biking home, we were stopped by our town cops who chastised us for missing baseball practice. They would go on to raid the party, kids scattering into the woods and bedding down in the ferns, like fawns, only to slink home in the morning.

The party had been Brian’s idea, like most things we did. Before he started dragging me around I’d been a bookish, anxious kid with a few buddies. I lived with the feeling that there were a second set of eyeballs perched behind my head that watched fidgeting hands. A second set of ears that heard my voice and made me queasy at the sound. But drunk, everything moved to the front. Drunk, I lived in the world that’s directly in front of my face. I just was, I just did. Words fell out of my mouth and if I regretted them later, what later? There was no later. There was no time.

The word, I think, is id.

The adults in town mostly shrugged about our parties. We were boys being boys. And boys we remained for the next six years, eventually throwing our own parties and running from cops. We spent weekends stumbling around bonfires or at our older friend Cody’s house, fighting over the stereo. Brian and Cody loved country and with enough effort I could drink myself into fandom too. Over the course of a night I’d go from nodding in a corner to screaming Garth Brooks with the bros:

I’ve got friends in low places, where the whisky drowns, and the beer chases my blues away. And I’ll be okay. I’m not big on social graces, so won’t you step on down to the Oasis because I got friends in low places.

I liked that song because I thought it was true. Nobody in my hometown went to college but I was planning to leave those boys. They treated me like Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting, even if their dreams had already been treaded upon. Cody had dropped out of college and settled at a factory job a few towns away. Brian was living alone, his dad having moved in with a woman in the next county. But he told me not to worry. We’d always have those slurred nights. He saw himself as Johnny Cash, me as Willie Nelson—blood brothers, real highwaymen, outlaws defined by their differences. But between our constant embarrassing fuckups and our diverging life paths, we were more like white trash iterations of Seth and Evan from Superbad.

He told me not to worry. We’d always have those slurred nights.

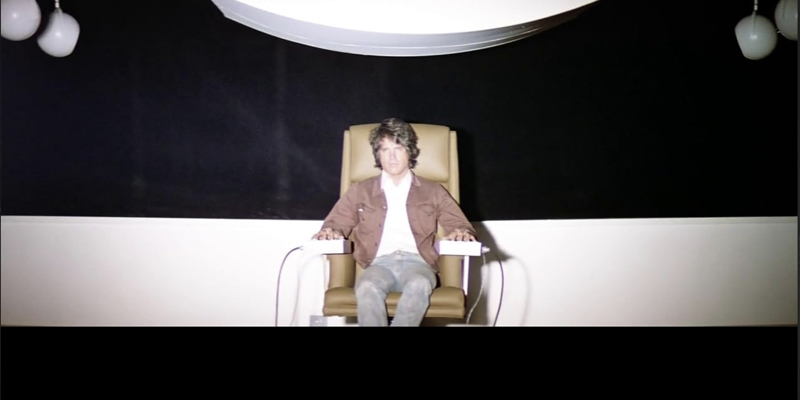

The first time I saw Superbad—shortly after its release in 2007—I was off at college, having shed the senior sendoff angst at the heart of the movie. It’s a familiar trope: Evan and Seth are high-school seniors whose close, co-dependent friendship seems to be ending as graduation looms. Uncool and horny, and flanked with their spazzy friend Fogell, they try to find booze for a big party, break into the popular circle, and hopefully get laid. Taking place over the course of one night, the plot still somehow feels epic in the way that long drunken nights feel epic when you’re young and the world is endlessly large, but benign.

Seth and Evan don’t get laid, but they do get shit faced and talk through the fact that they won’t be college roommates. Their high school dreams were just that—dreams. But it hardly matters. Lying in sleeping bags in Evan’s basement, they express their platonic love for each other. “I’m not embarrassed,” Seth says. “We should say it every day.”

But bros learn young to speak through the bottle. The next day, their nighttime promises redacted, they partner off with their crushes instead, their friendship serving more like a practice run for romance.

Superbad was directed by Greg Mottola, but carries the hallmarks of the producer, Judd Apatow, a teen take on the bromance genre he developed during the 2000s. The word was coined by journalist Dave Carnie in the mid-90s but wasn’t widely used until Apatow’s work became popular and culture writers began declaring every male friendship a bromance. By 2010, we’d witnessed a decade of Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, four years of Dwayne Wade and LeBron, three years of Obama and Biden. But unlike those relationships, centered on shared work and purpose, the friendships of the bromance are brought to us mostly by booze. Even in Apatow’s The 40 Year Old Virgin, where the male characters are all co-workers, it’s a few slurred nights that bring them together. Drinking your way to a friendship that relies on drinking to sustain itself—that’s the experience of most men I know. If the genre gets one thing right, it’s that booze is the tie that binds.

In the summer of 2007, just after Superbad came out, Cody died when another friend of ours drove them into a ravine in the late model Ford Mustang he could hardly afford. The friend, let’s call him Justin, was playing a game of cat-n-mouse with a carful of young women on the way up the hill from a country bar called The Don’t Know Tavern. Cody was passed out with the passenger seat reclined at the time of the crash. He’d been passed out there since getting 86’ed from the bar for falling asleep on his stool. The coroner said he probably never woke up.

There are usually three bros to a bromance and Cody had felt like our third. He was Fogel, an understated, lovable loser that could hold the protagonists together. A big sluggish guy with lazy eyelids, he was quiet, funny, and much smarter than he let on. He lived for those epic nights, though. The spare bedroom in his house was devoted to drinking games. He had a beer pong table signed by everyone who ever played a game on it. It was covered in terrible cliches. The only one I can remember quoted Hunter S Thompson—“too weird to live and too strange to die.”

The last time I played a game on that table, I was on break from my first year of college and the casting, I realized, had flipped. I was the third bro—maybe the fourth or fifth—the token nonconformist, long-hair, stoned. But maybe it had always been that way. Alcohol often tangles more than it ties, and it’s hard now to trace the threads of friends who never knew each other sober.

His house had been a total mess, bagged beer cans stacked to the ceiling of the porch. He’d just gotten a DUI and couldn’t take the cans to the recycling center. His drinking had gotten bad, but I don’t remember asking him about it. I don’t remember ever asking him about anything real, but this I know: after he’d passed out with the stereo blaring, Brian and I gathered the empties and built pyramids of cans around his house. One on the toilet seat, another in the shower. One outside of his bedroom door, rigged to collapse, and another on the hood of his car. The piece-de-resistance was one on his coffee table, head-high and gleaming like a shrine, which I suppose it was. Brian and I stood marveling at our work before we tiptoed away, giggling like imps.

I don’t know if Cody thought it was funny. The next time I saw him was his funeral.

The spare bedroom in his house was devoted to drinking games.

I got stoned beforehand. I don’t really know why. My dad was working, so he couldn’t come, and I sat with the bros in a pew at the old Lutheran church at the edge of our town. The church had been built as a hexagon so there were no corners for the devil to hide in. It didn’t feel coincidental that we were ushered as close to center as possible. We’d held a little wake the night before and the smell of it was leaching from our pores.

The preacher was a local truck driver and amateur singer who spoke about God at the request of Cody’s mother and stepfather and read the lyrics to Lynyrd Skynard’s “Simple Man” at the request of Cody’s father. Had he been a simple man? Fuck if I knew. I knew he liked Jeff Foxworthy and Wu-Tang Clan. I knew he’d been in the gifted program at school. I knew he was great at math. I knew he drove a car previously owned by a disabled guy; he accelerated and braked with toggles on the steering wheel. Once, because he didn’t have a bottle opener, he opened six beers on the trunk latch of that car and drove home from work. When he’d told me that, I broke out laughing.

The funeral was strange, like everyone there was mourning a different person. At the end, the preacher hit play on a boombox he had behind the pulpit. Some shimmery guitars started up, followed by cellos. None of us knew the song until the preacher started in with his raspy baritone: “I hope you never lose your sense of wonder.”

Brian turned toward me and his eyes held the horror of Lee Ann Womack. Next to him, our bro Matt was too distraught for embarrassment. He was the only one of us to cry, and he tried to hold it in as the song continued, each verse worse than the last. At the bridge, the preacher became dramatic, singing in whispers. He was literally pointing at individuals in the pews and making long, rock-and-roll eye contact as he prowled the pulpit. He was staring right at us at the crescendo, telling us we had a choice, telling us not to sit it out, telling us to dance, and when it ended, no one in the church knew what to do next. We were a communion of the stunned. It was the worst thing I’d ever heard. It felt like high parody. It felt like a scene in one of those movies we loved, which is maybe why Brian said what he said.

Matt was crying loudly and Brian turned him. He had one hand clasped on Matt’s knee and another on his shoulder. “Matt,” Brian whispered.

Matt turned toward him.

“That was fucking horrible.”

Matt burst a single note of laughter, a release of air that could be confused for a sob. I thought no one had noticed. I thought we were adults. But when all the mourners shuffled out, I heard a lady whisper, “I hope this is a goddamned lesson to the kids in this town.”

I still think a lot about that woman. Did she want me to hear her? Did she think it would matter? Death doesn’t happen for our betterment. But even if it did, there was no consensus on its lesson. Our dads said sad shit happens. Our moms said get designated drivers. The country songs said Cody would be throwing down in heaven, burning rubber on some golden highway.

And film? Funerals were for sadboy shit like Garden State. In the bromance, it’s always graduations or weddings or pregnancies that signal when it’s time to grow up. The plots can be different, but closeness is what’s at stake. True emotional vulnerability is both the reward and the risk of drinking, but in the bromance, the consequences stop there. Nowhere is this clearer than Todd Phillips’ The Hangover. Three friends wake up in that trashed Vegas suite to find a live tiger in the bathroom and a crying baby in the closet. The real problem is what’s not there. Their memories of the previous night and their buddy Doug. The set-up stumbles onto a darker truth: When you lose a drinking buddy, it’s often hard to really remember them.

He was the only one of us to cry, and he tried to hold it in as the song continued.

Recently, while re-watching The Hangover, I noticed a pyramid of beers in the opening scene and in a flash I remembered Cody’s contagious smile and the sour smell of those cans. Was this where we got the idea? I checked the release date—2009, two years after his death. I wondered if he would have liked it, if he would’ve appreciated the middle-class version of himself reflected back. Brian did, quoting the movie endlessly when he drank.

I was drinking too much and alone when I started rewatching all these bromance films. At first it felt like nostalgia without the sharp pang. There’s a solace in the message: male friendship isn’t meant to last. It has to flame out, like young love, but can be rekindled for a weekend with the right conditions. The trio in The Hangover could just as easily be replaced with Seth, Evan, and Fogell, or with Brian, Cody, and me—men who will never again be as close as they were as kids. So maybe we drink to go back. We drink to go back to the feeling that closeness is possible, even if the same bravado that we try to rekindle is the thing that keeps us apart.

Even though we were young when Cody died, that’s what the drinking fast became. It was an idiotic summer-long wake. The mood was ennui. Woozy-eyed, stilted, drunk. Every night at bonfires or trailers or dank apartments, where his name cooled and became like a blister on the tongue. Because we couldn’t talk about it, because we’d never seen men talk about it, we assumed drinking about it was the next best thing. As to what we did, besides drink and snort Vicodin, I don’t really remember. Once we tried to go fishing together but Pat jumped in the creek, spooking the fish.

We acted like it was what Cody would have wanted. Sometimes Brian would say, “Let’s go see Cody,” and we’d drive my old Buick to his grave, where visitors left Coors Light and cigarettes and a small toy car, Dale Earnhardt’s #3. We’d pour out a beer on the ground for him, probably like we’d seen in some movie. But even then it felt a little like acting. I began to realize that I’d never really thought of him as a full person, as real and complex as me, until he was dead. He’d always just been a bro. What right did I have to mourn? Had I realized what he meant to me after he died, or did his place in my life grow and embellish like the stories we tell ourselves? All this time later, I still don’t know.

A selfish guilt saddled me that summer. That woman at the funeral was right: the lesson eluded me. I dropped out of college. My dad wouldn’t speak to me. I felt if I just stuck around long enough life would begin to make a little sense. But if the bromance teaches us anything, it’s that an era is always closing. Our last hurrah would be a weekend in August, 2007, during the town festival we’d all loved so much as boys.

We drank to oblivion and took all the Vicodin we could find. The pills, an early first wave of the opioid epidemic, seemed to come from everywhere at once: an uncle, a brother, a doctor’s pen. I hardly even knew what they were. I hardly even cared. What even happened that weekend? Man, I guess you had to be there. Our bro Curly got attacked by an angry neighbor with a baseball bat, and Curly fled so fast that he ran straight out of his shoes. Then the neighbor stole his shoes. Cops came, the shoes were returned, all of us under twenty-one had to hide. Our friend Tuft—nicknamed for his very hairy ass—drank a lot of Absinthe and wallowed in a puddle in his underwear on Main Street. Brent hooked up with Brian’s date in the bathroom, where the keg was kept, leaving Brian crushed and the rest of us thirsty.

The mood was ennui. Woozy-eyed, stilted, drunk.

I got so drunk and high that I lost my car, walked home, and lying skyfaced on my parents’ back porch, surrounded by the night hum of Pennsylvania summer, I cried like a kid. When my mother found me, I was maudlin, saying how sad I was, and how I didn’t want to leave my friends, and that they were good friends. Really, except for maybe Brian, they weren’t. But I’d been humbled by grief, disabused of my own invincibility, and I was confusing my private realizations for shared meaning.

At the end of that summer I left town. Eventually I went back to college. Brian found out his twenty-seven-year-old ex-girlfriend was pregnant and moved in with her. (Unlike in Knocked Up, a few baby books and a new apartment didn’t fix their problems.) Tuft got his girlfriend pregnant, too, and by the time I came home to visit they were already joking about the trouble their boys would get into together. Justin was released from jail and bought another fast car. Some of the guys limped to adulthood, and a few others went further into pills and booze, never really landing from their fall from the pram.

Brian separated from the older girlfriend after a couple of years, around the same time he started telling me he loved me. He met a nice woman and had a little girl. He goes to work early and stays away from bars. He tucks in his daughter each night and volunteers on the town council. He cuts firewood for the old people in town. He voted for Trump, twice, because boys will be boys will be boys. That’s part of the reason we don’t talk much anymore, but really, it’s because you can only retell the same story so many times before the humor’s all wrung out of it. You can only toast a dead friend’s life so many times before the life becomes a myth, and a myth makes a hero. How do you think I started writing in the first place? Here’s Seth in the basement, on a laptop, on a word doc, on a page.

“I’m not embarrassed,” Seth says. “We should say it every day.”

I was maudlin, saying how sad I was, and how I didn’t want to leave my friends.

So here it is:

I loved the last time I partied with the boys. It was a cool night in July of 2018 and Brian and I were drinking at the American Legion when Tuft wandered in. A little while later Justin entered, sitting sheepishly at the end of the bar, where he sat for years after the accident, having his two drinks and getting a ride home. Eventually he joined us and before long it was decided that we should find something better to do. With a cooler of bad beer we drove a dirt logging road through the woods with the cruise control set to twelve miles an hour, for safety. We blared those same Johnny Cash songs. We threw beer bottles at trees and shot road signs with a BB gun. I felt a throwback feeling, nostalgia for the moment as I was inside of it, like we were making a low-budget sequel or a one-off reunion. We were. Even in the moment I knew I’d never really hang with those guys again.

On the ride home we leaned out the open windows and screamed that we’d all fallen into a burning ring of fire. But the center of a ring is empty, hollow, and soon the night was over and I was standing in the quiet field behind my parents’ house. The lightning bugs were scrawling their names in the air. I must’ve sat down. I must’ve laid down because the dew had settled on me by the time I woke shivering. I jumped up into the night—alone, spinning, thirty-years-old— and I puked onto my own two feet.