Nearly forty years before the Stonewall uprising—often incorrectly pegged as the moment in history when queer people first began experiencing pride in our identities—Ruth Fuller Field, writing under the pseudonym Mary Casal, published her autobiography, The Stone Wall, where she details a life largely defined by her ferocious pursuit of women.

Even then, Field wasn’t ashamed, nor was she interested in hiding her desire. It felt like the most natural thing in the world to her and when she met Juno, a woman with “the most beautiful hands” in 1892 on her first day in New York City, she began a “rapturous period of wooing”. A bouquet of violets, a trip to the theatre, a kiss—Juno became the great love of her life. It’s striking to read that not only was Juno introduced to Field’s family, but that, considering the time period, it went so well. “Juno and Mother loved each other from the very first. To her death, my mother was always happy in our love and friendship for each other,” Field writes in The Stone Wall. (Any speculation on the connection between the name of Field’s autobiography and the name of The Stonewall Inn has been so far disproven.)

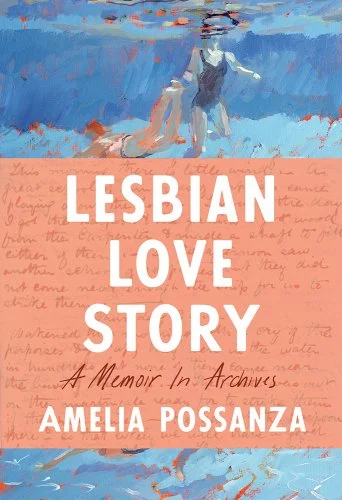

Their 200-year-old lesbian love story is one of the many documented in historian Amelia Possanza’s new book, Lesbian Love Story.

It’s a sexy, illuminating tour through sapphic history. I spoke with Possanza, who is also the Associate Director of Publicity at Flatiron Books, about the history of lesbian resistance she uncovered, how queerness has been criminalized throughout history, and the lesbian stereotypes that have persisted: “We had a lot of pre-1950s U-Haul situations.”

Jeffrey Masters: There’s a moment you write about where you say you decided to become a “collector of lesbians”. Can you talk about that moment and what you meant by that?

Amelia Possanza: I feel like that is sort of at the heart of what I was setting out to do. I grew up without a lot of lesbian role models in pop culture and history. My mom is a librarian and my dad is a classics professor, so I was surrounded by books. The fact that there wouldn’t be a lesbian in a single one was wild to me.

The moment you’re talking about was when a friend on a queer swim team I had joined—you know, a place to go find lesbians or at least be seen as one—did not recognize me as such. And part of me had to forgive him because I’m like, If I’m not seeing them out in the world, where would he see them?

In the spirit of my librarian mom and the literal card catalog in my house growing, I want to make the little card catalog of lesbians for myself and invite other people to come add to it. I’m not going to find them all. So, I took the lack of representation that I saw growing up along with my love of reading and collecting things and put them together.

JM: For the earlier stories you write about where they didn’t use or self-identify as lesbians, how did you grapple with that?

I was interested in who took the risk to live an authentic life, and to be queer.

AP: I think what really intrigued me was to sort of take people on their own terms and use the words that they used. For some of them, like Mary Casal, who didn’t call herself a lesbian, I discovered that she had been asked to write this autobiography by sex researchers and they called her a lesbian. Some people think that the word may have been removed from her autobiography because we don’t have the original edition. It was edited by these two men who asked her to write it. While she didn’t use the word lesbian, she was very much in that milieu. It was attached to her.

I wanted to be really careful. I didn’t want to write a book about people who were suspected to be lesbians. I was interested in who took the risk to live an authentic life, and to be queer. Mary, she doesn’t use the word, but what I love about her and why she ended up in the book, is because her whole book is about her passionate love for another woman and feeling like she was out of place. She was like, “I don’t want to marry a man. What’s wrong with me?”

JM: I found Mary Casal so compelling because she was living in the late 1800s, early 1900s, and she wasn’t hiding or suppressing her desire for women. We’re often told that this embrace of one’s queerness only began after Stonewall.

AP: Yeah. For a long time people in my community were like, Oh, we’re living at the best time to be queer. And I think now, we’re all really starting to question that. This is maybe where the queer people I’m writing about are separate from the stories of queer men. They were sort of given the grace and were able to have really close, intimate friendships with men. They could live together. And around this time, when Mary was alive, women could get an education and have their own jobs and make their own money. They didn’t need to get married to have a husband’s income. And it was this little pocket of time before queerness really became pathologized, when they could live almost openly. Mary even told her mom what was up and her mom was just like, whatever. Go for it.

JM: Criminalization is a recurring theme. The law was being wielded against queer people in almost all of the stories, which feels, unfortunately, prescient today.

AP: Hugh Ryan was such a huge inspiration for me in his book. His second book, The Women’s House of Detention, is so much about how in the early days, prison was a place to put a woman who wasn’t a woman “in the right way”.

JM: He writes that a woman could be locked up for wearing pants, smoking, or simply staying out late.

AP: Also, the definition of prostitute used to be like, “Oh, you’re alone on a corner”. That could be considered solicitation or prostitution. And it’s sort of like, if they truly are a prostitute, there’s got to be customers right? But they’re not going after the men.

I should also give a little asterisk that so much of this depends on who you are. If you’re a Black woman, how you’re presenting in the world…many of these rules were built for middle-class white women.

JM: Going into a project like this, you had certain expectations. What surprised you the most in the research?

I want the sex scenes. I want the romance.

AP: I was struck by how much resistance these lesbians put up. I think I was like, “Oh, I’m going to find romance.” People had their sweethearts and there was definitely a lot of that, but every single one of these people found a way to carve out a space for resistance and refuge. One of the lesbians, Rusty Brown, was being sent to Bellevue for shock treatment and had the intelligence to ask someone what shock treatment was, then steal someone’s uniform, and run out of there in the nurse’s uniform. The resilience and rebellion that was eye-opening and it was not what I went in expecting since I was like, “What’s romantic love about?” I think the definition of lesbian, as it’s grown and shrunk over the years, is about so much more than that.

JM: So much of the queer and lesbian experience has changed in recent years, but what hasn’t changed? What are those overarching commonalities that still exist?

AP: One unexpected, surprising thing, which is maybe telling since I unconsciously picked people who are a little bit like me in their presentation, but everyone was either made fun of or self-identified as sort of hairy or not beautiful. I loved the repetition of that. They were hairy or unsightly or just bad at performing gender. Rusty Brown was literally arrested in a dress for being a female impersonator and went to jail and she was like, No, no, I’m actually a woman. I’m just really bad at walking in heels. And no one believed her.

And the other commonality that surprised me, which is such a huge lesbian trope, is a lot of these people found a partner and they were like, Great. Move in with me. We had a lot of pre-1950s U-Haul situations.

JM: Can you talk about the format? It’s not a traditional history in that you fill in gaps and create scenes for the characters based on your research. Was that something you found in the writing process or was that always the plan?

AP: It was something that I found in the writing process. I want the sex scenes. I want the romance. And if you’re reading something that was edited by two men who self-identified as sexologists and wanted to publish something that they didn’t want to be branded as an obscenity, it’s not there. Who knows if Mary Casal wrote some really explicit moments that were taken out? But I want to have those. And I also think a lot of times in academia, there’s a questioning of like, Oh, no, they’re just friends.

I wanted it to be the kind of juicy emotional history that, unfortunately, I don’t think we’re going to get. And part of me too felt a little bit of that anger that we don’t have this because there are all these rigorous rules about history. I wanted to give myself permission to defy them because these rigorous rules haven’t been helping marginalized groups.

What I also found in the writing process was that they are all actually overlapping, right? Mabel Hampton’s chapter is the second one and it’s a lot about the 20s and the Harlem Renaissance. But she lived through World War II, so there’s this opportunity for her to come up again. I think that also created some moments for imagination. It was interesting to think about where their circles or timelines overlapped. They’re not seven separate, totally isolated stories. One is flowing into the next.

JM: There is also the inclusion of Amy Hoffman (Hospital Time) and Mike Riegle. It’s an intimate, yet platonic relationship in a book about love stories. Why was that important for you to include?

AP: I feel very tender about the two of them. I started out being like, Hmm, what’s my love life going to be like? How am I going to solve the mystery of my love life by asking other people about theirs? I think eventually it became about the ways that all of these forbearers of mine are living outside the usual script. Friendship then became a really clear way that that happened. Going back to the law, so many state-sanctioned resources are tied to marriage and weren’t an option.

I’m very intimidated by Michel Foucault. Toward the end of his life, he gave this beautiful interview with a French magazine called, “Friendship as a Way of Life.” This young man was interviewing him and was like, “What does it mean for you to be gay?” And he says this beautiful thing about how the point of being gay is not like, Oh, I need to analyze my own sexuality and come to the truth of it. It’s about asking, what are the relationships I can have in the world? How could they be different? I’m gay and I just loved that. I was so moved by that.