Translator’s note: Since October 17, 2023, Heba Al-Agha has been sharing her diary through her Telegram channel “Talk of Life and War.” The entries include poetry, freeform narration, descriptions, and photos, as she is forced to move with her family from their home in Gaza City to Khan Younis, then to Rafah, and as of May 2024, to Cairo. This is a selection in translation, arranged chronologically.

*

October 17, 2023, Gaza City

Exodus to the south

We packed only two emergency suitcases—one with IDs, documents, and certificates, and the other with a few changes of clothes. It wasn’t easy, compressing your life into a suitcase, but these are the things we have to do.

On Friday night, the streets were crowded with displaced people from other parts of Gaza. We tried to sleep after an agonizing day. Warplanes had bombed the home of some relatives in Khan Younis, neighbors of my parents. We wept for Mhannad, his siblings, his mother and father.

That night we made a lot of sandwiches for those displaced in our building. It was, as they say, the Last Supper.

In the middle of the night, rumors started to circulate as everyone exchanged messages about orders to evacuate Gaza City. We ignored them, doubted their veracity, exhausted every possible discussion topic, and tried to get some sleep.

In the morning we found out that the rumors were true. Messages had continued to circulate, and they were confirmed when we watched the officer on television order Gaza residents to evacuate within 24 hours.

I found myself weeping, bitterly, in disbelief. How could we possibly make the decision to stay or leave? How could we leave our house, our city?

We emptied suitcases of textbooks, notebooks, coloring books, and replaced them with underwear, a change of clothes, a towel, and other supplies. I crammed as much as I could into each bag. I was looking around the house, crying, then cramming in some more.

We don’t own large suitcases. I haven’t traveled since 2014, my husband since 2008 when he finished his studies in Egypt. We used what bags we had and gathered what mementoes we could: photo albums, a favorite pillow, toys, dolls, Yara’s sketchbook, Kamel’s sports uniform. I packed my Quran, my laptop, the novel I Saw Ramallah, and a signed copy of Ahlam’s An Autobiography of Taste. Do we really have to leave right now? And what will the journey be like? Will we be safe?

I hear them calling me from downstairs. Everyone is waiting. I try to delay as long as possible.

The sound of explosions is continuous. Fear gets the better of us. We hug, we pray, we ask God for forgiveness, we bid farewell to the relatives starting to scatter. We take the road of fear and tears, waving goodbye to our house as we head south.

*

November 1, 2023, Khan Younis

1:54 pm Death lies next to us every night, but stays alert, waiting for the signal. We wake up to a miracle: we’ve thwarted death as well as sleep. Time overtakes us—from every side and from above. Daytime takes it all in, agitated and distressed. We no longer fear death. We have come to fear life.

2:54 pm We are living a forbidden life. Our dreams dangle from bombed roofs, from shattered glass and ruins, from the remains of our miraculous life. Gaza lays siege to this miserable, sick world—besieges it so it can’t eat, drink, or sleep. Gaza lies on its broken stone, resting on the shoulders of its children. Gaza leans on its slow death, to live.

*

November 11, 2023, Khan Younis

Dear Hana:

I found a letter I wrote to you last May during the short war. It was a Saturday and I wanted to share that I hadn’t felt Friday go by. The same thing happened yesterday. I didn’t feel the day go by. I can’t feel anything, Hana.

Are you ok?

I keep trying to reach you, keep getting the damn “your call cannot be completed.” I keep calling, sending text messages. My heart tells me you are safe.

Do you think back to our chats about this obscene world? These days the obscenity is on full display: a world without scruples baring its sharp teeth, acting outside nature, outside truth. This world does not represent us, Hana, so we should expect nothing from it.

Are you able to get bread? Cans of beans, feta? Are you craving a fresh green salad with avocado and olive oil? Remember the knafeh we had at Saqallah? They destroyed the shop when they bombed the Watan (Homeland) tower. They’ve destroyed the whole homeland, not an inch spared for us to take a walk together, for our new and impromptu friendship.

Hana: I am in need of a good chat and an even better cry. But these are luxuries when there is no time to cry, grieve, or wallow in the memory of my house, abandoned in stricken Gaza. So I swallow my tears, drinking them in place of the water that’s been cut off.

I’ve tried my hand at kneading dough, baking with firewood, laundering in a big tub, and cooking in massive quantities (lentils, beans, pasta). My back has been killing me without my beloved bed and favorite pillow. My heart aches when I realize that a whole month has passed since we left home. Do you remember my home?

Everything in the house had a reason for being: the barren wall, the pictures in the wooden frame, the different pieces here and there, the small details I delighted in. The painting behind my desk was intentional too, meant for when I logged on to the online sessions in the Master’s program. I had recently come to believe I could aspire to higher education. Last night, some neighbors who stayed sent us photos of the house and its broken windows. We were overjoyed to see it still standing.

My mother and the other women keep repeating, “Praise God, we are better off than others.”

Dear Hana, reality is brutal. Death is looming and voracious, like an ogre swallowing everything in sight. Speaking is difficult, but so is silence. I see that we are afraid. Afraid for our loved ones, for our homes, our fate, our future. Afraid for our beautiful country that has been shattered. Afraid because our hearts are stuck in our throats, and there is no one but God, my dear.

*

December 19, 2023, Rafah

I feel empty, barren, trapped inside stolen time. I am filling my head with repetitive news and repetitive images, with the saddest voices in the world. I practice the perfect reaction for when my family dies … if I survive that is!

The days run us over like trucks that don’t kill us. We duck between the wheels to survive one more day, which is always harsher, colder than the day before.

The worst part is how the displaced person dies a cold, ordinary death far away from home, in an unfamiliar city that doesn’t resemble them. But that is death: the absent present suspended in mid air, allowing us to live until the end of the year.

I have made no plans or bogus resolutions for the new year. No getting in shape or investing in healthier eating. No plans for professional training either … I’m not even sure I’ll be able to finish my Master’s.

My mother is now very far away. We stayed at her place for 52 days until they ordered us to evacuate that area too. We had to go our separate ways. We’ve only met up once since, right before we moved to the southernmost part of Rafah. My mother packed her pride for the displacement, and it has her in agony. Pride jabs into her like a thorn every night, refusing her rest.

Displaced once again. I carry with me the memories of my home, of my family home, of my two cities. On leaving Al Mawasi, we were separated from dozens of my relatives. It wasn’t easy to find a place in Rafah. But after a very long day in the car, I secured a small room for my immediate family of four.

This room is our home for now. With every move, we shed more luggage. Charitable people give us mattresses and blankets—we weren’t lucky enough to buy some at the start of the war. New fears grow here. Life is harsh and I try to make do. We buy exorbitant canned goods and wait in long bread lines in this city packed with people. At last, we were able to get some flour. I go door to door and return home carrying my treasure of bread, and we all bask in this fleeting moment of joy, and thank God.

Our days consist of searching: for water, for an outlet to charge our phones, the toilet flush that everyone can hear, the warm bath for the little ones, a colorful clothesline. And we do it all under non-stop bombing, in this city they claim is the safest.

The war has relieved me of quite a few thoughts and relationships that have dropped like unpicked olives. I will be crossing into the new year lighter, holding only loyal friends and my family, which has proved precious, sacred, in this terrifying moment.

*

December 20, 2023, Rafah

I walk the streets of Rafah alone in my prayer clothes, holding a cloth bag with today’s bread. I no longer care what I look like. As I walk back to our room, I think about how much I used to care about style, about my jeans and colorful shirts, my favorite bags, the white shoes I had gotten into lately. I think about how we didn’t pack any winter clothes and couldn’t find any to buy, and how my sister leant me a warm robe to wear on my latest exodus.

I try to enjoy the fleeting moments, like when I look at the faces of passersby or meet new people, or when I learn new words and recipes. I take in the streets, the markets that have never been so crowded, the many homes we have stayed in. Even when we had to stay on the street, we turned it into a sidewalk picnic.

Language feels shallow and antiquated. Idioms are as salty as the water we are drinking. There is no place for luxurious speech or embellished prose. The martyrs do not read our words. The wounded are too tired. Maybe the only reader these days is someone who has been displaced like me, or a friend abroad who reads in solidarity. They are not concerned with craft, only with the content of our writing. Maybe they wonder how we are able to write amid every obstacle to life.

The loaf of bread I’m carrying resembles the earth, their colors bleeding into each other. The earth is hungry for martyrs and homes, and people who are hungry know this. They know the earth will soon devour them too, so they eat their loaf in peace, mixing the dough into their flesh so they can be eaten together. Bread, human, earth—all joined together as legend, as roots.

The truth is I am only an amateur writer. I do not belong to any writers’ unions and have not published any literary books. But I work with an army of young writers, have trained my children in freedom and told them that writing is power. We cannot surrender this magic wand. We have no choice but to exist.

*

December 21, 2023, Rafah

Yara covers up her teddy bear who has been displaced with us, and tells him to bundle up. “If you get sick, there’s no medicine.”

My little girl knows how bad things are. She joins us when we discuss how to prepare fool without a clay pot, or without salt. She coaxes her dad for one or two biscuits from the aid shipments that are being sold on the street. She argues they’re affordable, if expensive, hoping for this small luxury of childhood.

Kamel is always trying to get more than his daily bread ration. He tells us his hunger is too great to bear, and reminisces about delicious meals from his previous life. He promises to get me a big sack of flour. It breaks my heart and I let him dream, cursing this moment that makes us count our children’s morsels. But we have no choice, we must ration everything lest we end up with nothing.

Things are different here in Rafah because we are alone, no extended family to hold you at the end of the day. We were forced to leave my parents’ house in Khan Younis on December 2, and we couldn’t find new refuge together. Through my family’s heartbreak that day, I relived my first displacement, when I left my own house in Gaza. Some days we regret leaving, others we thank God we did.

Most of the day is devoted to figuring out what we’ll be able to eat. In the end, it is almost always the same meal, though we try to exercise choice whenever possible. When firewood is available, we prepare a grand tomato stew or a decent lentil stew. And, of course, we have the Egyptian cheese sandwiches.

The word “displacement” haunts me. It comes at me through cold windows, on scary nights, from the moaning of the little ones when they get sick. It catches me off guard if I’m laughing or distracted, curls up in suitcases, spills into empty water bottles, sticks to our feet as they tire in search of tissues or a can of oil, hops onto the carts and buses we catch rides in. It rides along in our car with every new exodus. That is the only time we use the car to preserve what is left of its gas.

*

December 23, 2023, Rafah

Hana says she prefers death to displacement, that she cannot imagine leaving, that her home is her soul.

Mine too, Hana. In those last moments at home, I packed in a frenzy through tears and gasps, in absolute disbelief. But we got out. We got out, Hana. Some called us cowards. Others said not to go south because the situation is the same everywhere. It is difficult everywhere, that’s true. But in Gaza City and the north, the genocide defies description. In the south, the genocide gives you a chance at life. You can find water; even if it’s salty, it’s water nonetheless. In the north, your days are numbered. You will die either of fear, hunger, or bombing, but you will ultimately die. In the south, you will die too, but at least you get a funeral prayer, a last laugh, the luxury of searching for the basics of life. Frankly, it is difficult to make these comparisons, but I am certain the difference is there.

Our colleague Hamed was martyred, Hana, by a sniper’s bullet in Sheikh Radwan. Polite, gentle Hamed. He had stayed in Gaza City for his sick mother. Many friends and acquaintances are still there: Haidra; my husband’s uncle and his wife; our colleagues Walid, Haidar, and Raed; and many others. The army is besieging some of them, shelling others, killing some outright, and sniping at others for entertainment. They leave some witnesses to their terror, who may die anyway of grief and rage. Haidra sent me his latest poem two weeks ago, before we lost contact with him.

Everything is impossibly difficult. In the exodus between cities you will walk alone, but may chance upon a tent, a friend’s room, a family that takes you in, or a family that gives you its apartment. Can you believe that some families moved in with relatives to make room for the displaced? People are incredible.

The most desirable option is renting a room or apartment, but those opportunities are rare. If you manage to find one, you settle in only to be displaced again and restart the impossible search.

People are trained in displacement. From the west to the east, then to the center, then the south briefly, back to the center, then west again. They chase us around then have fun executing us in the streets. No ambulances, communications, or deliveries. No aid, water, or food. All the failed attempts hang over the shoulders of the most corrupt policymakers on earth.

Displacement is heavy. You feel heavy just thinking about how you are a burden on already fragile, struggling cities. But you are forced to be there. And they are forced to host you. You come without anything and lay claim to everything. If you are lucky, you left with blankets, a mattress, a sack of flour, and a gas canister. If you left under bombing, displacement is even worse.

There are two types of displaced people: the smart one who tries to get along with their hosts, be a help to them, share everything; and the burdensome one who thinks they are a guest and expects everyone to serve them simply because they are displaced, oblivious to the fact that their hosts are also suffering.

I left my house two and a half months ago, but I felt the deep pain of displacement when we evacuated my parents’ house after the truce ended. I left a lot of belongings behind as I fled in disbelief, convincing myself we would return for them the next day. You know, Hana, every day I travel in my mind to my house in Gaza City and to my parents’ house in Khan Younis. I visit my closet and wear whatever I want, sit in front of my screen drinking sahlab, curl up in my favorite blanket, savor my mother’s noodles, warm myself with her room, her face. I open the fridge, which transformed into another cupboard during the war, and take out a bag of bulgur. I cook for my children and for my heart, which cannot be warmed.

Displacement is forced on you, Hana. No one leaves their home willingly.

*

December 25, 2023, Rafah

How do the homes bear our absence?

The homes we left behind are not made of ordinary walls. They’re our bodies, our flesh, our memories, our anger and our joy. They are men, women, children, the family portrait hanging on the wall.

These days, our homes are asleep on top of one another. No doors, no windows, no embraces at the front door, no flower pots or trees. The elegant ones with paved driveways have lost all their features. Those that had gardens are now buried in them.

Not much of family is left in these homes: a grandson’s scent, a paternal aunt, half a maternal aunt, a grandmother’s remains. The war has taken them all, neighbors included, leaving a single witness behind who will join them later.

Widows are no more, nor mothers of martyrs. They are no longer in fashion in Gaza, where we now mourn a family in its entirety. We review the civil registry and highlight all their names in red, a black mark against humanity.

As for the survivors, they left their home for the unknown, for the frosty cold, for an exile of tears and grief. We have become “the displaced” in the media and host cities, another burden on this bereaved homeland. We left our souls at home.

How does the house spend its time without us? Does it miss our voices, our movements, the kids’ endless bickering, how we slowly surrendered to sleep at night? I am reminded of the slowness, of how much I longed for it and how life always found a way to speed me up. I relished the slow moments, holding on to every opportunity for gratitude. I was grateful even for coffee, though abundant, sipping every cup slowly.

Flavors have changed. Coffee is different in displacement: full of strange hints, and expensive too. We had stocked up on it, but it ran out. The war keeps going and the wait demands much coffee, and much patience.

Nothing tastes the same. Familiar meals now taste hollow, deficient. We no longer feel at ease with the dining table. Yet when we eat, we summon the house, inviting it to share the dishes of displacement with us. And in this way, the house too is displaced. We were gone too long, so it too was forced south through the safe passage.

“At least we’re safe,” is how we end every conversation about the house. As if anyone is safe from the bombing. We all wait our turn, it can happen anytime and anywhere: at home, on your way home, in the place to which you have been displaced. Bombing is everywhere, safety with God alone.

*

January 5, 2024

An Identity for Unidentified Bodies.

1. My father’s snoring hadn’t been heard for two weeks. We check and he’s not at home. Two of my brothers go looking for him. My uncle and his four children follow, on their way to fill water for the laundry. My uncle’s wife waits for him. She goes out with her son-in-law Mahmoud to look for all of them: my uncle, his four children, my two brothers, and my father. No one returns.

2. Aunt Widad was not home alone. Her sisters, hajjehs Samiyya and Safiyya, were taking refuge in her house. The blood of all three mixes in the old family house. The bodies disappear.

3. Hasan, brave owner of a donkey cart, would carry martyrs to the hospital. Hasan disappears and the donkey is left alone.

4. Saraj’s final call to his mother: “Mama, I am sorry, I am inside with the Israelis.” No news since the last call.

5. In the big blue schoolyard, under large banners reading UNRWA, fifty men are blindfolded in their underwear. All are taken, only ten returned.

6. The road south is long. Yaser faints. Yaser is diabetic. “Leave him, keep moving!” yells the soldier through his megaphone. I walk on. I don’t go back for Yaser.

7. Uncle Saber has dementia. He leaves our place of refuge in the south and is never heard from again. When the sniper’s bullet touches his forehead, Uncle Saber recovers his memory.

8. “He’s wearing gray sweatpants with orange stripes.” On the autism spectrum, he walks by without a word, heading east. Trees bloom there. A big red apple comes out of his heart, and the earth reclaims it.

9. Ihab was carrying a laptop bag and holding little Rima’s hand. We walked for a long time. They summon us through the megaphone. We never see Ihab again. We keep walking alone.

10. They arrested Fatima at 5 am. Fatima is blonde and hazel-eyed. The next morning the women return to the neighborhood. Fatima does not.

*

January 17, 2024

Good morning, Gaza time.

I am back to writing after losing contact with the outside world. I was losing my mind without an internet connection or any way of communicating. I kept shielding my face from the sirens outside, kept returning to the window to tell the world I was still alive, kept looking to the sky knowing I wouldn’t find any birds there. I was afraid of being forgotten by the world while I was out of reach.

What is the meaning of being alive yet far away from life, not sleeping, not eating, not living at home, not being able to raise our children as we would like. Our children have stopped growing. They grow only in the ledger of time. We are stuck in the night the war started.

We try to forget about time. We are tired of counting the days off the floor. They pass us timorously, the days, oblivious to our age, pregnant with disaster, throwing us around without mercy. We cannot fathom the cruelty of what is being done to us, how the world can be so unethical and conniving.

What happened while we were gone? What did the civilized world look like, knowing that a small part of the world is freezing and drenched, with nothing to warm itself with, locked behind a big gate as they beat it up relentlessly.

What did the civilized world look like, knowing that this small part of the world sleeps outdoors, on the floors of hospitals and schools, in small corners here and there—that it has to buy food at obscene prices while civilized countries send some biscuits.

The scales have fallen from our eyes: It is a cowardly decadent world with selective humanity. For years, it fought for the rights of women, LGBTQ, athletes, animals, and then, in the moment of truth, turned its back on us without pity. Brown skin, brown hair, hazel eyes can be left behind.

From the blackout, we salute everyone who has tasted brokenness, hunger, and deprivation.

From the blackout, faces seemed sadder and more anxious, obsessively trying to check on loved ones scattered around Gaza. No news, air kisses, or waves from our crowded displacement. Fate threw us into our displacement like birds forced to migrate to the warmth only to find out that everywhere is cold.

*

February 3, 2024, Rafah

Today my little girl turns ten. This birthday will pass simply, without ceremony, bakeries, toys, or Disney costumes. This birthday will pass lightly, without sugar or chocolate or even candles.

We chose to place a virtual candle on a can of red beans. We chose red beans—instead of a can of chickpeas or tuna or peas, or a loaf of bread—for a simple reason: We had never had red beans until the war. Having tried them, we’ve decided they taste like their sisters, and that the only difference between beans is their shape. Red also sparks the imagination, and the beans in Jack’s famous tale were a symbol of making dreams come true.

Yara was born a few months before the 2014 war, and during that war I wished I hadn’t had her. But she grew up and lived through several wars, and now through the most catastrophic one of all. This war has robbed her of the warmth of a home and a life, colored her drawings black, and replaced her dreams with thoughts about hunger and how to satisfy it. Her options: fried tomatoes, a sandwich of canned chickpeas, or biscuits that are not meant for sale but which we buy on the street for 4 shekels.

We tried our best to bake a cake, but every time we gained an ingredient we lost another. We held on to the eggs as long as we could but eventually had to cook them. Flour became abundant, but oil is still a treasure. And forget about any fancy ingredients like vanilla, cream, icing, or a cake mold.

We debated whether to celebrate reluctantly in displacement, with some biscuits and popcorn, or whether to postpone the celebration until we are back home in Gaza City or her grandmother’s house in Khan Younis. Yara decided what she wanted most was to choose her meals for the day: a breakfast of fried tomatoes just for her; for lunch, either some bean stew or a feta manoushe baked by the women in the nearby refugee camp.

With every new situation, my daughter turns a new age. She asks about the price of cooking oil, eggs, canned beans, tahini, lemon, and tomatoes, and about the capacity of a gas canister or batteries. Onions, once her sworn enemy, are now a favorite. Her textbooks, storybooks, toys, and clothes are in the past.

Happy birthday to my little Yara. May the years to come bring us back the life we used to have. May we live a little after this war, my child, enough to revive our withered spirits. May we be well, and may you grow like an apple tree that stays forever young.

*

March 6, 2024

Ode to khibbayze!

In displacement, we trade anecdotes of misery. I tell my brother that I ate some khibbayze (mallow) and licked my fingers. He snorts, “The day has come when khibbayze is finger-licking worthy!” Yes, my dear, for this plant with its iron, vitamins, and nutrients, is superior to all the aid trucks stuck at the crossing, better than any food parcel dropped by a plane deliberately in the sea. Khibbayze is the alternative to the chicken and meat distributed “secretly” among acquaintances, or sold at obscene prices. Khibbayze saved my friend Ghadeer from the famine pulverizing them in the north.

We’ve never had to buy khibbayze. My mother would pick it after a good winter, all shiny, tender, and green. Whenever she shared her cooking with a neighbor or a family member, the ground teemed with it. The picture of health, my mother would stand in the sun, gathering the leaves. Now the land is gone, and my mother can no longer move.

Some prefer khibbayze to mlukhiyya (its Jute variation) but others are fundamentalists: only mlukhiyya will do. Some cook it as is, its leaves whole; others chop it and add grain, making maftool. As for us, we eat it alone, no accessories needed.

I am proud that this plant is a daughter of this land. She did not betray or humiliate its children, preserved their dignity when the famine came and the springs dried up. She quenched thirst and hunger, became a symbol of survival, helped us weed friend from enemy. So, dear Gazan, depend only on what is rooted in the land, for what comes from crossings and markets is temporary, fleeting. Only the children of this grieving land remain.

*

March 20, 2024

Everything tastes insipid, meaningless. Every story is gutting, every image is shocking, and the news keeps getting worse. There is nothing good on the horizon. Those far away couldn’t care less about us. Those nearby can’t see beyond surviving the day, collecting crumbs from a world that no longer has any value for the people of Gaza.

Ramadan has arrived timidly, offering its apologies to the hungry, condolences to the mourners, and solace to the displaced. It has found a people without a land, home, or guide, stumbling through life on this narrow strip of earth, grasping onto it, asking God to deliver them from this horrible nightmare.

We call my uncle’s wife in Gaza City. She tells us excitedly that they found some qatayef made of flour and sprinkled some leftover powdered sugar instead of the customary syrup. Here in the south, shops and stalls are full of qatayef, sweets, and nuts. Those who can buy them at all do so in limited quantities, just a taste. Others who cannot afford them break their fast on the canned food from the aid packages, which is neither filling nor nutritious.

The market is full of everything, at astronomical prices. Price gouging at its ugliest, never before seen in Gaza. The displaced wait in humiliating lines for a frozen chicken no bigger than the palm of your hand, a small bottle of cooking oil, a kilogram of sugar, or some Nescafe. We wait for reasonable prices in an utterly unreasonable situation. Meanwhile, coverage seems scant. It is as if everyone wants the war to continue in order to suck the remaining blood of our people—the blood that was inoculated from death by fate, only to be sucked by the black market.

Amid all this, I wonder about the point of writing. Who is reading? Who cares what we say? I start writing a post and don’t finish it. The drafts pile up. What’s the point of our lives, now that they’ve lost all color, worth, or importance. What’s the point of the human, now the cheapest commodity in this place of exorbitant commodities. What’s the point of fleeing time and again to protect your family if all the safe places are a lie, and all the shelters are a hoax.

What’s the point of speaking and writing when humanity has deafened its ears and shut its eyes? Even outside Gaza, they are screaming into a void. No one hears their chants, no one sees their demonstrations. And we continue to be stuck. We wait to die, pretend to live, and desperately try to find new lives here or abroad, or even some small joys: a hot meal, a warm touch, or even some humble katayef.

*

May 9, 2024, Cairo

Fear flows from my blood

out of my mouth

delivering me to yet another exodus

through my four limbs

it gnaws on the flesh of patience

stakes itself on a plastic tent

so hot it melts on my back

Then it carries our putrid belongings

on a mare that has tasted every road

delivered us every odor

but the smell of home far far away

Father says to pack summer clothes only

Mother says the winter ones too, for this one may last

My little sister shoves the Frozen shirt and woven tights

once again

my brother lugs the firewood, the heavy bag of canned goods

At this camp, all the tents had Arab names

all the disappointments too

a Qatari tent

an Emirati tent

a Kuwaiti tent

not one of them was here

Every time, we are alone

Alone …

and forever.

*

May 31, 2024, Cairo

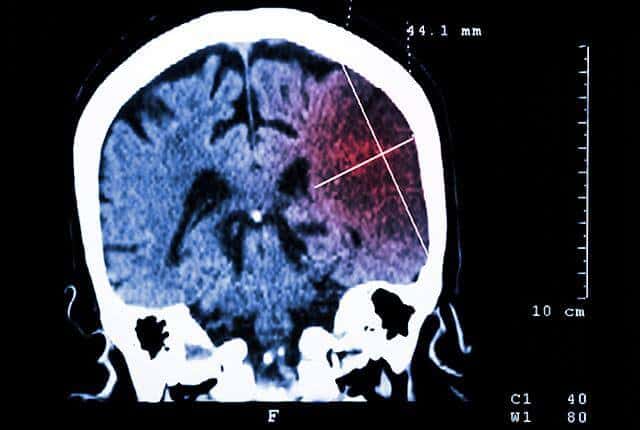

This morning Hana sent me this photo from the beloved city of Khan Younis. Looking is painful. Such destruction makes you very small. It shrinks you, wounds you, robs you of all forbearance. The nothingness makes you lose your balance. How could one look at this scene dispassionately, and carry on? Where would such callousness come from?

Nothing is left on this earth to sustain life. Nothing to help you live, to complete you. Even if you are the only one who deserves to live.

*

Translated by Julia Choucair Vizoso.

You can help support Heba and her family here.