Christine begins to fixate on certain turning points in her own history—what might have happened otherwise, if she’d made different choices.

Sometimes at night she wakes with a watery, stranded sensation, as if something that might have been hers is dissolving. In dreams she reaches for keys, cups, doorknobs—her hands slide through them. What if she had gone to some other college, or moved to some city other than New York? (But what, then, if she had never known Daisy?)

She knows it’s useless, to give attention to what can’t ever change. But it’s vivid, mesmerizing, to consider other lives.

The preoccupation reaches peak futility when Christine and Daisy move from Ditmas Park to the new apartment in Bushwick. An old boyfriend lives nearby; he and Christine meet up for a drink. He mentions he is dating someone new, and Christine feels unexpectedly annihilated. It’s as if something breaks open beneath a fine seam she’s been holding closed, effortfully, all her life.

She didn’t think she still had feelings for him, even. Now she ruminates on: how did she lose him, what mistakes did she make here? She lies on the new IKEA couch and cries endlessly, her grief like an infection. Daisy makes tea, she sits and listens. If Christine had not responded unkindly that one time. If she had not gone away that one summer. If she did not have such a temper. Then what, then what, then what?

I think I’ve fucked up, Christine says, her hands over her eyes. But Daisy is gently skeptical. No way, she says. You’re just going through something. She fixes a piece of Christine’s hair behind her ear, and her hand is soft on the side of Christine’s face. It’s hard when people move on, Daisy says. But at some point you have to just pull it together.

In January Daisy gets into astrology, with zeal. She’ll absorb herself with research on her laptop for hours, then emerge from her room to disclose her findings, her laptop balanced in the crook of one arm, the other reaching to switch on the tea kettle.

I think what’s going on with you is the influence of your moon in Capricorn, she says one night.

Christine has been watching television in a small, bleak trance, a blanket pulled up over her head. She makes herself sit upright in her cocoon. Moon in Capricorn feels very alone in the world, Daisy is explaining from the kitchen. I keep coming across the word orphaned.

And I have that? says Christine. Daisy is taking mugs down from the cupboard, her arm stretched up to reach the highest shelf. The tea kettle is beginning to steam, frantically.

Yes, says Daisy, That is what you have.

By February they’ve unpacked most of their boxes. They each turn twenty-seven—Daisy first, then Christine. On the morning of her birthday, before work, in their kitchen, Christine makes coffee and tries to explain how, for the first time ever, she is experiencing her age as a problem, a sort of mismatch. I feel too messy to be twenty-seven, she says. Twenty-seven should feel clearer. I haven’t achieved it. For one thing, I’m a receptionist. A temp receptionist.

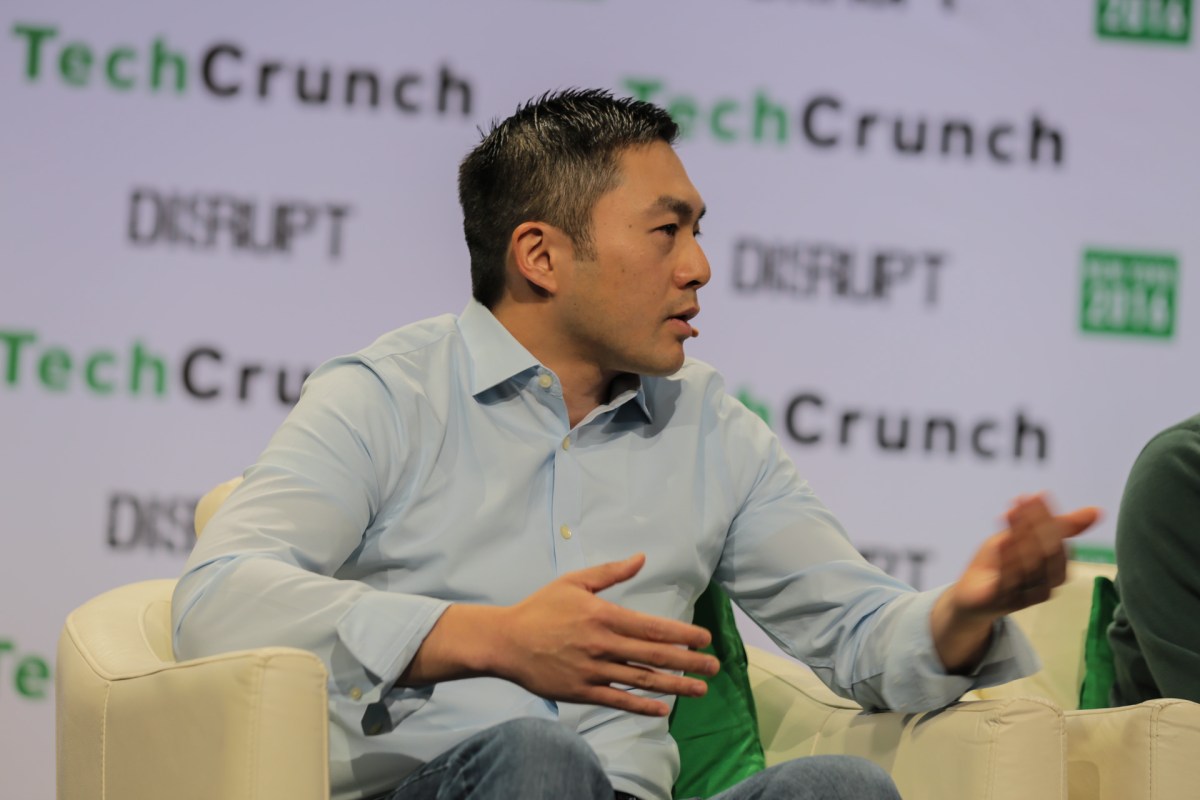

Outside their window, it’s starting to rain a little. The kitchen light casts both their faces in a warm glow. It could be worse, says Daisy, who has a better job, at a startup, writing marketing copy. She says, I’ve been twenty-seven for days now. Christine makes a show of frowning as she pours herself some coffee. It’s a joke, Daisy says. Come on—it’s funny. Can you pour me a cup too?

That weekend they throw a shared birthday party. Daisy emails the invitation with the subject Two Pisces Emote About the Passage of Time. They both find that extremely clever, but the party is only okay. Christine drinks several cocktails too quickly, becomes ensnared in conversation with a co-worker of Daisy’s. They talk about a movie Christine loves, and he tells her that it’s overrated—Not that I’ve seen it, he adds, but from everything I’ve heard. Later, someone by the bar puts a hand on the small of Christine’s back to move her aside as he passes, a gesture so proprietary that Christine has to excuse herself, seething, to smoke a cigarette outside. Men think they can just move us out of the way, she says to the girl who gives her a light out on the sidewalk, and though she offers no context the girl says: For real.

I always forget I mostly hate this bar, Christine says later, while they both stand in line for the bathroom. Daisy leans her head against Christine’s shoulder and says, What we like is the idea of it.

For a birthday gift, Daisy buys Christine an astrological reading, to be conducted by video chat. Christine sets it up for the following Tuesday night—she emails the date, time, and place of her birth in advance. The astrologer, ethereal yet severe in the blurry chat window, explains that Christine’s natal chart shows a complex gathering of planets in her Twelfth House of Self-Undoing.

Also, he says, her Mars placement makes her impulsive, direct, and prone to irritation. It’s important you find healthy avenues for aggression, the astrologer tells her, as if he were prescribing a vitamin. You might take up martial arts, he says.

Impulsively, Christine does. She signs up for a class at the gym, and actually she finds she does love it, loves to punch and smack and kick, loves the way her leg flares out to meet the impassive bulk of the punching bag. Sweaty, shaking her hair out of her eyes, she feels exquisite, powerful, nearly divine. She goes back every week. She begins to feel better.

You are a goddess of war, says Daisy, who sometimes comes along to the gym, to use the bouldering wall. She reports that whenever she stops for a drink of water, she can see Christine in action through the glass door to the kickboxing room. Later, after her class, Christine will always join Daisy at the bouldering wall, and the two of them stand before its warty, multi-color grips, chalking their hands while Daisy points out ascents she expects Christine can handle.

Daisy is experienced at this, whereas Christine has almost no technique. She enjoys it, though: the trial-and-error climb, and then the controlled fall from the top, like she is a cat dropping out of a tree. Also she finds it hypnotic to sit and watch Daisy—balletic and agile, her shoulders bare in her tank-top, her hair in a braid down her back. You’re gorgeous up there, Christine tells her admiringly, one night after Daisy finishes a climb and is wiping chalk from her hands.

Daisy responds, grandly, I’m gorgeous everywhere. She twirls then, she kicks over her water bottle, so then they have to run to the locker-room for paper towels. I’m an idiot, says Daisy on her hands and knees, sopping up water, laughing.

Afterward they wash their hands, side-by-side at the locker room sink. Daisy cups her palms, splashes water over her face. Then she meets Christine’s eyes in the mirror, water running down her cheekbones and neck.

Okay, Daisy says. Can I tell you something?

*

And this is what unnerves Christine: the unseen potential in people she trusts. Lurking injury, how anyone could hurt her, leave her, any moment. She wakes at night, gripped with a steep and breathless dread. She dreams she is married to someone wonderful, but then she is knocking on their door and he won’t open it. He keeps coming to the window, but when he sees it’s her, he lets the curtain subside placidly back over his face. He looks resigned, though each time she knocks, he returns again to the window. It’s as if he’s hopeful someone is coming who isn’t her.

She dreams this too: Daisy walks through the apartment refusing to acknowledge Christine. Not in an angry way, exactly, only with the discipline of someone who has made the best decision, the clear and necessary choice. She looks, maybe, a little smug. Eventually she has Christine’s room removed, physically, from the apartment, sliced away as if it were an enormous square of cake. Afterward they stand together in the kitchen, and when Daisy finally speaks, her tone is relieved: I didn’t anticipate missing you, she says. And as it turns out, I don’t.

On this night when Daisy says at the gym that she’s moving to Austin, Christine describes the dream in detail, aware she is trying to seem maximally vulnerable and pained. It’s a terrible dream, she says. It makes me feel alone.

Maybe she can convince Daisy not to do it. They’ve decamped from the gym to a nearby bar, somewhere they can have a beer and talk this over, as Daisy put it. Daisy is quick to tell Christine that sharing the dream is a low blow—utterly low, she says—and unfair to disclose in this particular conversation. She says, You want me to feel worse than I already do.

Fine, says Christine hotly, Forgive me. She feels like a skipping record. We only just moved, she keeps saying, inanely. She gestures to the bartender: another. But Daisy is patient. I know, she says. It’s just that the job came up and I want the job.

It wasn’t intentional, she says. Surely you can understand that.

At the end of March they break their lease. Daisy is the one who takes the couch, because Christine has not yet paid her back for it.

Christine rents a studio—before this, she has never lived alone. The little couch she buys is delivered to the first floor, deposited in a cardboard box by the stairs. Afterward, she is unable to arrive at a satisfactory explanation of how she moved it to the third floor on her own. I guess I sort of rolled it end over end, she says to Daisy on the phone, I must have. The memory is vague. Daisy laughs and says, Did you black out or something?

The studio looks out on the backs of other buildings. In April, Christine tries growing plants on the fire escape—but then there is a strange, late snowfall, and in the middle of the night she has to bring them all in and set them by the radiator as the little cones of snow melt down. I’m sorry, she says to the plants, I didn’t foresee this.

It isn’t quiet, her new neighborhood. But somehow it’s like her apartment is hermetically sealed, hushed and silent as a small church. Sometimes this is serene and reminds her of childhood, of unearthing certain pleasures of solitude, lying across her bed, lost in thought. Other times the isolation of the apartment is an experience of disorientation and strange grief. Having watched Daisy box up her life and let go of what she would not be bringing with her, Christine decides to clear out many of her own belongings. She appreciates the sensation of stripping away what once delighted her—a feeling like she is getting out ahead of the inevitable. She bags clothes and sets them by the door, and the silence of her apartment seems to divorce her from context. She could be any person, anywhere.

Daisy texts When are you visiting? Will it be soon? But something is shifting. I can’t come, Christine tells her. I have to stay here.

She says it because something in New York is beginning to obsess her—she feels a small, troubling dissolution around her own sense of belonging, a feeling like she’s watching over an animal that could run from her. She has to stay close. In the silence of the apartment, she feels like she is drifting with the tide, and she tells herself out loud: You live here. And she thinks of Daisy’s astrologer who said: This is a watery phase of your life. You’ll feel like you’re going in circles. The current is taking you where you can’t see. As a child she moved frequently, it’s something she’s always been proud of, it makes her feel unusual, interesting, special. Daisy has always been jealous: All I have is Ohio, she likes to say.

Now the question of home transfixes Christine.

New York is the only city she’s lived for more than five years. It’s where she first became alert to the pleasures of knowing a place. Sometimes she cannot fathom Daisy’s choice to go, it seems to her like severing an artery. New York has symbolic weight for me, she says one night on the phone—and it feels, to her relief, like she has finally found words to describe all this. But Daisy only laughs at her: New York has symbolic weight for everyone, she says, I hate to break it to you. Later, she sends Christine a photo of herself, wearing a short-sleeve t-shirt, eating tacos in the sun.

But Christine means something different, about the accrual of personal history. About what it is to walk through this city and feel stirrings of meaning arise in places she has been. She misses the feeling of knowing her friend is in the next room, or will be home later. She liked feeling seen in this daily way by someone, in the course of years. With Daisy gone she finds her ideas about home and where she might locate it flower out disturbingly. When she’s alone, images come to her unbidden of living in all kinds of places—at the beach, in other countries, closer to her family, alone in a new city. The more ideas she has, the more possibilities she conjures, the more tenuous and unlikely home seems.

She finds her heart racing on subway platforms, or on weekend mornings waking up. She dreams she is living in an empty, quiet cube that has no door.

One day on the street, in May, the city becoming warm and living again, someone thinks he knows her, he pursues her up the block. I’m sorry, she tells him, turning at the corner when he touches her shoulder, I don’t think we’ve met—and then she is irritated to feel her eyes well up with tears. I’m so sorry I chased you, says the man, obviously mortified. I didn’t mean to upset you. I feel terrible. He runs a hand through his hair, he emanates concern.

No, this isn’t your fault, Christine is saying, wiping her eyes with the heel of her palm. No, I’m sorry, my friend moved. It’s hard to explain.

She tips her head back, and the pattern of clouds blurs and shifts like wet ink. Traffic grumbles in her ears. Let me get you a coffee or something, she hears this man saying to her, apologetic. I’m Luke. Could I do that for you?

Later Daisy will ask what even possessed her to agree. Very unlike you, she says, Though don’t get me wrong, I’m delighted. She adds, But please don’t ever marry him: Christine McQueen, what a terrible rhyme. I won’t be able to take you seriously. They both start laughing and then they can’t stop. I’m honestly having trouble breathing, Christine says into the phone. Daisy is cooking something in the background, her dishes clatter in Christine’s ear.

Then something shifts again.

She starts to find the weight of memory in the city oppresses her, infiltrates her present moment. Kissing Luke good night outside a bar, she realizes she once kissed someone else over there on the opposite side of Seventh Avenue. Meeting a college friend for a drink at a new place in her neighborhood, she realizes she’s been here before, only now the bar has a different name, has multi-colored lights strung up, license plates nailed into the wall, an imitation of a place that’s been here longer.

My friend lives there, she says too emphatically to the bartender, pointing at Texas above the beer taps, and he laughs at her a little cruelly. When the city starts to bleed meaning this way, it feels like a sequence in a movie, though she can’t precisely say how so. She feels like she is having an experience she knew would come to pass, as if she has traveled back to herself in these specific years in an attempt to change something immutable in her fate. She tries describing this to Daisy on the phone, but Daisy just keeps asking which movie she means. Not one particular movie, says Christine. I’m saying like a movie, you’re not hearing me.

She begins to consider how it would be to actually move away, a small experiment in self-betrayal. Home is deserting me, she tells someone at work, making coffee in the break room. She surprises herself by saying it, a very personal disclosure.

Sometimes she resurfaces from the subway onto some familiar corner, or the light hits the side of a particular building—and then she feels disbelief that the city existed before her and will without her. In books it always supplies a small thrill when a place of some private meaning is invoked: Washington Square Park, Amsterdam Avenue, the bar on Greenwich Ave. The Cooper Hewitt, the corner of 19th and Irving, West 12th Street. She writes exclamation marks in the margins, saves the moments of significance, intersections with her own existence. Other times it feels like she’s living in a kind of dreamscape where imaginary futures hover everywhere, mapped onto different points around the city: detailed, fading, insubstantial. Any time she’s in Bushwick—running an errand, or meeting a friend—she tends to imagine the years she and Daisy would have shared on Stanhope Street. She walks past the building and she’ll picture them inside: Daisy making tea, or Daisy saying, Calm down, don’t lose your temper with me, I’m listening.

So on the few occasions Daisy is seized by moods of regret, Christine takes a perverse pleasure in it. She likes them both suffering the same lost vision. One night Daisy calls in the middle of the night. I miss you, she says. I feel fucking stupid, I don’t know where I am sometimes. Christine turns on the light. She says, You’ll be okay.

When she thinks about childhood, about the games she would play, imagining herself grown up, she can hardly believe she is still living on that same continuous timeline. In bars on weekends, she and Luke and their friends discuss their place in the larger unraveling of everything. They discuss the person they can’t imagine will be elected in the fall, and should they have children in the face of looming climate catastrophe. The future feels like it is coming fast, like it will be terrifying. She considers how Luke is genuinely reliable—he would surely protect their hypothetical family in the inevitable event of environmental apocalypse, for example, and sometimes this seems like the clearest reason for being with him. He is a gentler person than she is, fundamentally: I don’t take anyone’s shit, she says to him in passing one night at his apartment, and though she’s talking about someone else, a co-worker who condescended to her in a meeting, Luke seems to recoil as if she is dangerous.

In a newspaper obituary around this time, she reads the sentence She did not suffer fools, and it is in an aspirational spirit that she writes it down and tapes it to her mirror. She remembers the astrologer highlighting her Mars in Aries: the wild unleashing thrill of adrenaline, any time she allows herself to say something cutting, storm away. One night in June she fights with Luke while they’re cooking at her apartment, she slams out into the street, into the humid dark night, and when he doesn’t follow her she walks miles through Brooklyn. She has no keys, no wallet with her—I have nothing, she wants to say to someone.

That’s a bit much, she can picture Daisy saying. I’m just one person who left. Your life is pretty good. She starts to have dreams of Daisy saying this, dreams where Christine tries to hit her but her hands are too heavy to lift. She wakes up mortified to have lost her temper, as if it really happened. Meanwhile in her waking life, she repeatedly loses her temper with Luke. It embarrasses her in the aftermath, it always does, her reactions looming out of proportion—her words heedless, unforgiving, and appalling when reviewed. She’d like to take things not so personally. Though Daisy has always adored her temper: It lights me up, she likes to say. It’s who you are.

Then it’s July, hot and damp. One night, Christine argues with Luke in a restaurant, and when she gets up and says she’s leaving, he lets her, as if defusing the tension is the thing that matters most. She can feel his eyes follow her out the door into the fine rain. Waiting for the light to change at 6th, she feels irritable and grim, disturbed and broken, and when a taxi blares its horn she says aloud to no one: Fuck you.

As if to punish her, the rain picks up with huge and ominous momentum. The light changes, headlights illuminate bright swaths in wet pavement. She crosses the street at a run and takes shelter under the awning of a closed bagel shop to root for her umbrella in her bag. When she realizes she’s left it in the restaurant, she tips her head back against the glass storefront, closes her eyes.

The sound of the cascading storm is a long unceasing hiss on the pavement.

Then a man and woman flail breathlessly into the space beside her, laughing helplessly. Christine opens her eyes, looks over to smile weakly in greeting, but they seem to barely register her. Oh my god, the woman is saying mirthfully, as she wipes her face with her hands, pushes them back through her wet hair like she is stepping from a shower. An expression of longing passes over the man’s face, and he reaches out and kisses her, and in Christine’s chest something desperate seems to unfurl.

It has been three months since Daisy moved. Through this first sad flush of their apartness, Christine has been unable to comprehend why other people’s happiness provokes her greatest longing for her friend. Daisy might smirk, if she were here—clocking the look on Christine’s face. She’d say to this couple, Excuse me, no displays of affection in front of my sad friend. Or she might turn to Christine with a parody of infatuation on her face and say, Should we also kiss? Probably we should, right? This is when the sound escapes from Christine, a wail that surprises her as much as it seems to surprise the other two. They turn to look at her with alarm. They will tell this story for years, Christine thinks. Probably they will laugh, recalling the overreacting girl in the rainstorm. And this inevitability fills her which such anger that when the couple asks, Are you all right? Christine steps into the torrent and doesn’t look back.

The city is a shiny, dissolving stain before her, it wavers in her vision. As she walks, she reaches into her pocket and dials Daisy, rain beading furiously on the screen of her phone, the drops clinging to each other. She presses send on the call, she hears the tiny ring and then the crackle of the line, a small opening in time and space. The phone is slick in her hand, as Daisy’s miniature voice in the storm says, Chris? Hello?

Just then the phone is falling from her grasp. It slips into a rivulet of water, a clear splotch of light, and goes streaming toward the storm drain. Christine gets on her knees; she’s like a child in a tide pool. Her hands are like two starfish in the water. The man and woman from the awning float above with their umbrella saying, Let us help you, tell us what you lost. The M8 bus is going past her, and the water rising from its wheels is bright abundant champagne gold. The rain is sliding down her face and neck, the phone keeps slipping from her fingers, the phone becomes a fish that swims away. The bus is disappearing toward the Hudson, but when Christine looks back here comes the same M8. Same graffiti swirled across its front, and so much tidal water rising up again. She is a skipping record. She is the phases of the moon. She is a city bus forever circling this route, as Daisy’s voice, below the water, tries to say her name.

*

“Two Pisces Emote About the Passage of Time” from I Meant It Once (c) 2023 by Kate Doyle. Reprinted with permission of Algonquin. All rights reserved.