The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

*

When I sit down in order to write, sometimes it’s there; sometimes it’s not. But that doesn’t bother me anymore. I tell my students there is such a thing as “writer’s block,” and they should respect it. You shouldn’t write through it. It’s blocked because it ought to be blocked, because you haven’t got it right now. All the frustration and nuttiness that comes from “Oh, my God, I cannot write now” should be displaced. It’s just a message to you saying, “That’s right, you can’t write now, so don’t.” We operate with deadlines, so facing the anxiety about the block has become a way of life. We get frightened about the fear. I can’t write like that. If I don’t have anything to say for three or four months, I just don’t write.

When I read a book, I can always tell if the writer has written through a block. If he or she had just waited, it would have been better or different, or a little more natural. You can see the seams. I always know the story when I’m working on a book. That’s not difficult. Anybody can think up a story. But trying to breathe life into characters, allow them space, make them people whom I care about is hard. I only have 26 letters of the alphabet; I don’t have color or music. I must use my craft to make the reader see the colors and hear the sounds.

My stories come to me as clichés. A cliché is a cliché because it’s worthwhile. Otherwise, it would have been discarded. A good cliché can never be overwritten; it’s still mysterious. The concepts of beauty and ugliness are mysterious to me. Many people write about them. In mulling over them, I try to get underneath them and see what they mean, understand the impact they have on what people do. I also write about love and death.

Anybody can think up a story. But trying to breathe life into characters, allow them space, make them people whom I care about is hard. I only have 26 letters of the alphabet; I don’t have color or music.

The problem I face as a writer is to make my stories mean something. You can have wonderful, interesting people, a fascinating story, but it’s not about anything. It has no real substance. I can fail in any number of ways when I write, but I want my books to always be about something that is important to me, and the subjects that are important in the world are the same ones that have always been important.

Critics generally don’t associate black people with ideas. They see marginal people; they just see another story about black folks. They regard the whole thing as sociologically interesting perhaps but very parochial. There’s a notion out in the land that there are human beings one writes about, and then there are black people or Indians or some other marginal group. If you write about the world from that point of view, somehow it is considered lesser. It’s racist, of course. The fact that I chose to write about black people means I’ve only been stimulated to write about black people. We are people, not aliens. We live, we love, and we die.

________________________________________

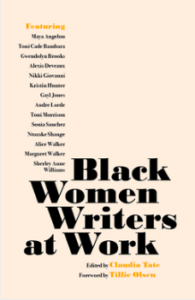

Excerpted from Black Women Writers at Work, edited by Claudia Tate with a foreword by Tillie Olsen (Haymarket Books, 2023). Reprinted with permission from Haymarket Books.