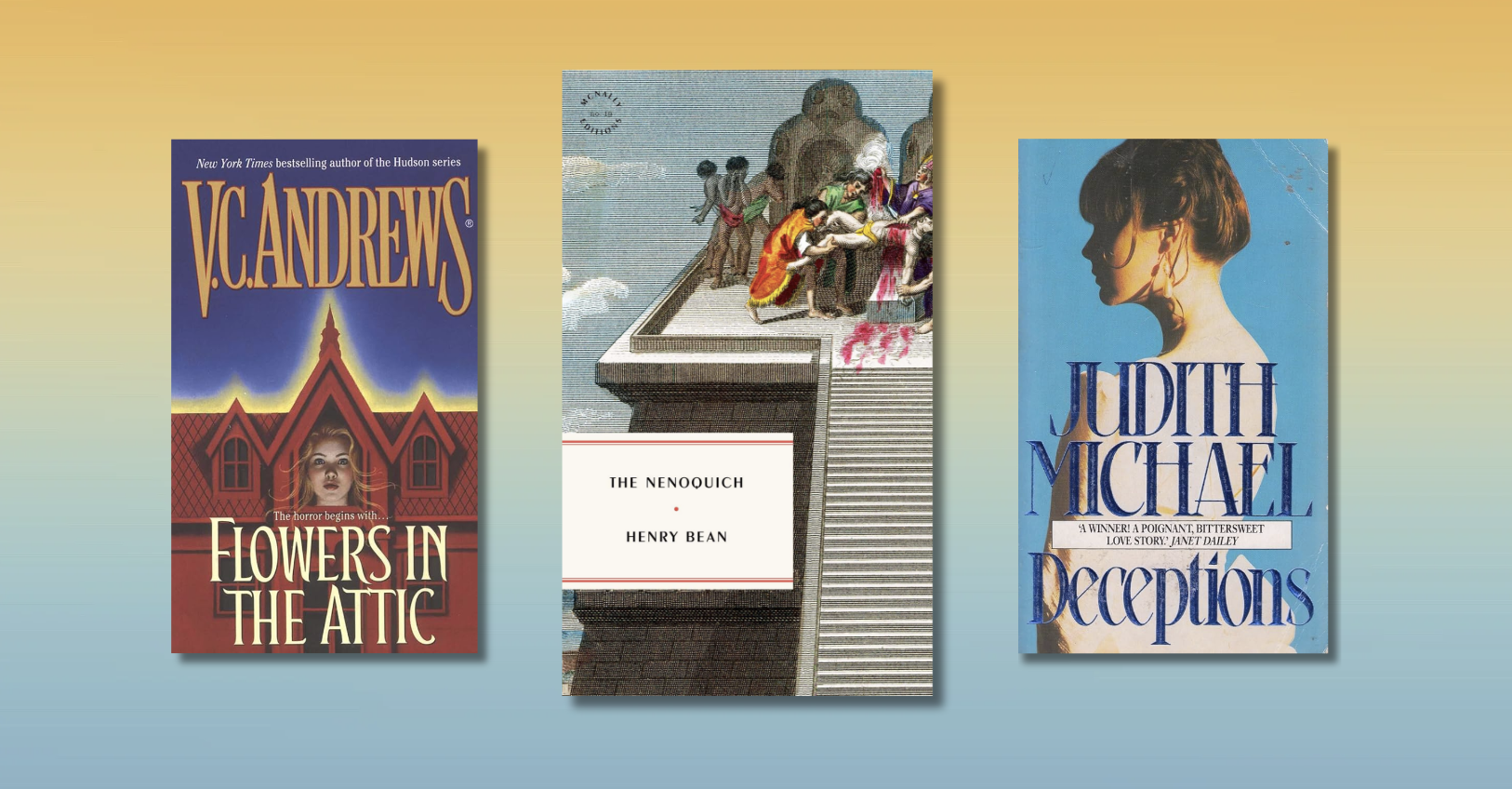

Last spring, Henry Bean, with whom I hadn’t been in touch for at least 30 years, sent me an email to tell me that McNally Editions was reissuing his first and only novel, False Match, under its original title, The Nenoquich, as part of its series of “hidden gems.” What thrilling news! Most first novels, unless the author goes on to write more, vanish and are never heard of again. And now, 41 years later, the signal novel of my career as a young editor was making a comeback.

Last spring, Henry Bean, with whom I hadn’t been in touch for at least 30 years, sent me an email to tell me that McNally Editions was reissuing his first and only novel, False Match, under its original title, The Nenoquich, as part of its series of “hidden gems.” What thrilling news! Most first novels, unless the author goes on to write more, vanish and are never heard of again. And now, 41 years later, the signal novel of my career as a young editor was making a comeback.

As it happened, that email was bookended by the deaths of two book publishing titans who were my models and inspirations: Dick Snyder, the tough, brave, unbookish marketing genius who made his publishing house function like a business; and Bob Gottlieb, the brilliant, erudite, and highly eccentric editor who was without a doubt the most important editor of the second half of the 20th century.

My first job in New York City was as a receptionist at Knopf; Gottlieb appeared at my interview and I was dazzled. Only three months out of UC Berkeley, I knew nothing of the publishing world, but I thought, “If this fellow’s running the show I want to work here.” Little did I know I’d be alone, “outside,” tethered to a Dictaphone with only the elevators and delivery men for company. I did see Gottlieb often, as he would greet his writers at the reception area instead of, as most did, sending out his assistant to escort them “inside.” I vividly remember him doing a full prostration before Robert Caro when he appeared one afternoon—his recently published biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker had just won the Pulitzer Prize.

I soon left Knopf, and made my way in the paperback world to finally end up, in 1977, as a senior editor at Pocket Books, the mass market paperback arm of Simon & Schuster. I was hardly qualified for the title, but I made the most of it.

One night after dinner, my good friend Humphrey Evans III, a budding literary agent, handed me the manuscript of a novel called Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews. It was only 90 pages, and I read it in one long gulp and phoned Humprey at midnight. “This is some weird shit,” I told him. “Horribly written but extremely powerful. I want it.” Flowers in the Attic, which I went on to edit, became an overnight sensation, and with the publication of her third novel in 1981 Andrews became the bestselling paperback author ever, and the fastest selling in Pocket’s history. Her novels become a genre of their own, and although she’s been dead for 35 years, mass market paperbacks under her byline continue to be published at a rapid clip.

One night after dinner, my good friend Humphrey Evans III, a budding literary agent, handed me the manuscript of a novel called Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews. It was only 90 pages, and I read it in one long gulp and phoned Humprey at midnight. “This is some weird shit,” I told him. “Horribly written but extremely powerful. I want it.” Flowers in the Attic, which I went on to edit, became an overnight sensation, and with the publication of her third novel in 1981 Andrews became the bestselling paperback author ever, and the fastest selling in Pocket’s history. Her novels become a genre of their own, and although she’s been dead for 35 years, mass market paperbacks under her byline continue to be published at a rapid clip.

I was at the time 29 years old; I’d only been an editor for four years, but there was nothing left for me to accomplish at a mass market paperback house. I had never edited a book I would choose to buy and read. I needed to get into hardcover publishing, where I could publish serious books. Dick Snyder, then the CEO of Simon and Schuster, wanted to keep me (and the many millions I was making for the company), so he arranged for me to also be an editor at the flagship imprint.

Erwin Glikes, the editor-in-chief of S&S, took me out to lunch, and said, “So, you want to be real editor!” I was outraged by his condescension. Yes, I was a green, young woman who’d made a splash in the lower caste world of mass market publishing, but I was a real editor. I wish I had responded by bringing him the manuscripts that V.C. Andrews would turn in to me and ask him to show me how he would turn those bloated reams of prose into multi-million bestsellers.

I soon presented two novels to the editorial board, those Olympians who would read my memos about the novels, dip their toes into the manuscripts and decide whether or not S&S should publish them. Deceptions by Judith Michael was a commercial novel about twins who trade lives for two weeks. One twin dies on a yacht, and the formerly jet-setting twin is suddenly trapped being a suburban mother and housewife. The Nenoquich by Henry Bean, was a stylish, mordantly witty, highly erotic novel set in post-60s Berkeley. A self-loathing writer in search of a topic launches a sinister seduction which has deadly consequences.

I soon presented two novels to the editorial board, those Olympians who would read my memos about the novels, dip their toes into the manuscripts and decide whether or not S&S should publish them. Deceptions by Judith Michael was a commercial novel about twins who trade lives for two weeks. One twin dies on a yacht, and the formerly jet-setting twin is suddenly trapped being a suburban mother and housewife. The Nenoquich by Henry Bean, was a stylish, mordantly witty, highly erotic novel set in post-60s Berkeley. A self-loathing writer in search of a topic launches a sinister seduction which has deadly consequences.

The editorial board’s response: “We think Deceptions is a good bet; we don’t think The Nenoquich is. Also, we’re confused, you’re known for very commercial fiction and then you present this very dark, very cerebral, literary novel. We can’t deny it’s well written, but this sort of literary fiction isn’t what you should be acquiring for us.”

I was devastated and furious. I knew agents would never send me serious books until I had published some, and The Nenoquich had come to me serendipitously through a friend. It was one of the best novels I’d read in years—of my time and place and people, and I’d never seen it captured with such steely brilliance. And I felt I’d more than earned the right to publish something I was so passionate about.

I began seeking another job and was soon offered a good position at a hardcover house. When I had one foot out the door, Snyder offered me an imprint at S&S. Not only did he see the V.C. Andrews bonanza leaving with me, he also seemed to like taking bold leaps of faith. As he once told the New York Times, “Ninety‐nine percent of the people in this industry are highly intelligent. The people who succeed are those who have the greatest commitment. Maybe it’s a neurotic commitment I look for. You want someone who does something that is impossible and then is worried the next day that he can’t duplicate it.”

To declare my intentions, the first book I bought for my new imprint, Poseidon Press, was Henry Bean’s The Nenoquich. It was published, on my first list, along with Deceptions, in 1982.

The sales force urged me to change the title, though both Henry and I thought the title perfect—unusual and provocative, like the novel. A nenoquich is one born during the five extra days in each 360 day cycle of the Aztec and Mayan calendars. During those days, no personal grooming, work, or business is done as the days were considered empty, cursed, and ill-fated. Nenoquich has been translated as “worthless person,” “will never amount to anything,” and “doomed to perpetual bad luck.” Had I been more confident and experienced, I would not have caved to their demands, but this was my first venture into the kind of publishing I really wanted to do. I’d never before published a hardcover book, and I needed the support of the sales force whom I’m sure were skeptical of my newly hatched imprint. Henry reluctantly came up with the title False Match—a cinematic term for a jarring discontinuity between shots—when time, images and spaces do not flow smoothly, and so it became.

Deceptions became a bestseller. False Match garnered rave reviews from several important newspapers and won a PEN Award for year’s best first novel. The Boston Globe said of it, “Unlike most fiction of the day, False Match will not lose its value. Literature lasts.”

As so often happens, the novel enjoyed a brief, unremarkable paperback life, then went out of print. Henry Bean became a highly acclaimed screenwriter and director. I enjoyed a fulfilling, 35-year career as an editor and publisher of both literary and commercial books.

And now, mirabile dictu, The Nenoquich has returned to life. Jonathan Lethem has called it “ a masterwork,” and Christopher Carroll of Harper’s has called it “remarkable,” writing that it lies “somewhere at the nexus of Highsmith, Nabokov, and Sentimental Education.” Unlike for its first publication, Publishers Weekly gave this a starred review and proclaimed, “Rediscovered, this stands as one of the great novels of adulthood’s losing battles.” After four decades of a false match, Henry Bean’s Nenoquich not proves the ancient prophecies wrong, but also brings hope to all of us who believe great literature lasts.

![‘Big Brother’ Recap: [Spoiler] Evicted First From Season 24 ‘Big Brother’ Recap: [Spoiler] Evicted First From Season 24](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/big-brother-first-eviction.png?w=620)