I first laid eyes on the Foo Fighters in England back in 1997 as they walked out onto the main stage of a newly formed rock festival. Dave was beardless, Taylor had short hair, and they played their set while it was still light out—somewhere between Prodigy and Placebo—because not many people knew about them yet. Not many people knew about the V Festival yet either, so there was space in front of the stage for a twenty-six year old female-presenting English person who was vaguely interested in what the drummer from Nirvana was up to now.

I’ll admit I can’t remember much about the set beyond the feeling that Dave and Taylor seemed to be in competition over who could make the loudest noise, but I do remember being pumped enough afterwards to go out and buy both of their albums, at a time when vinyl was expensive and money was tight. It was the beginning of an obsession with their music that would last for the next twenty five years; or to be more exact, twenty four years and ten months.

I didn’t care about the trivia, and I didn’t collect tickets like trophies. I loved them only for their music.

I don’t know what makes a true die-hard fan. Some people say it’s knowledge, a familiarity with the minutiae of every intimate detail about the band; some say it’s dedication, a disciple-like commitment to attending every show of every tour; some say it’s longevity, proof that you were the first kid at the first gig at the smallest, sleaziest venue way back when. But that wasn’t how I loved the Foos. I didn’t care about the trivia, and I didn’t collect tickets like trophies. I loved them only for their music.

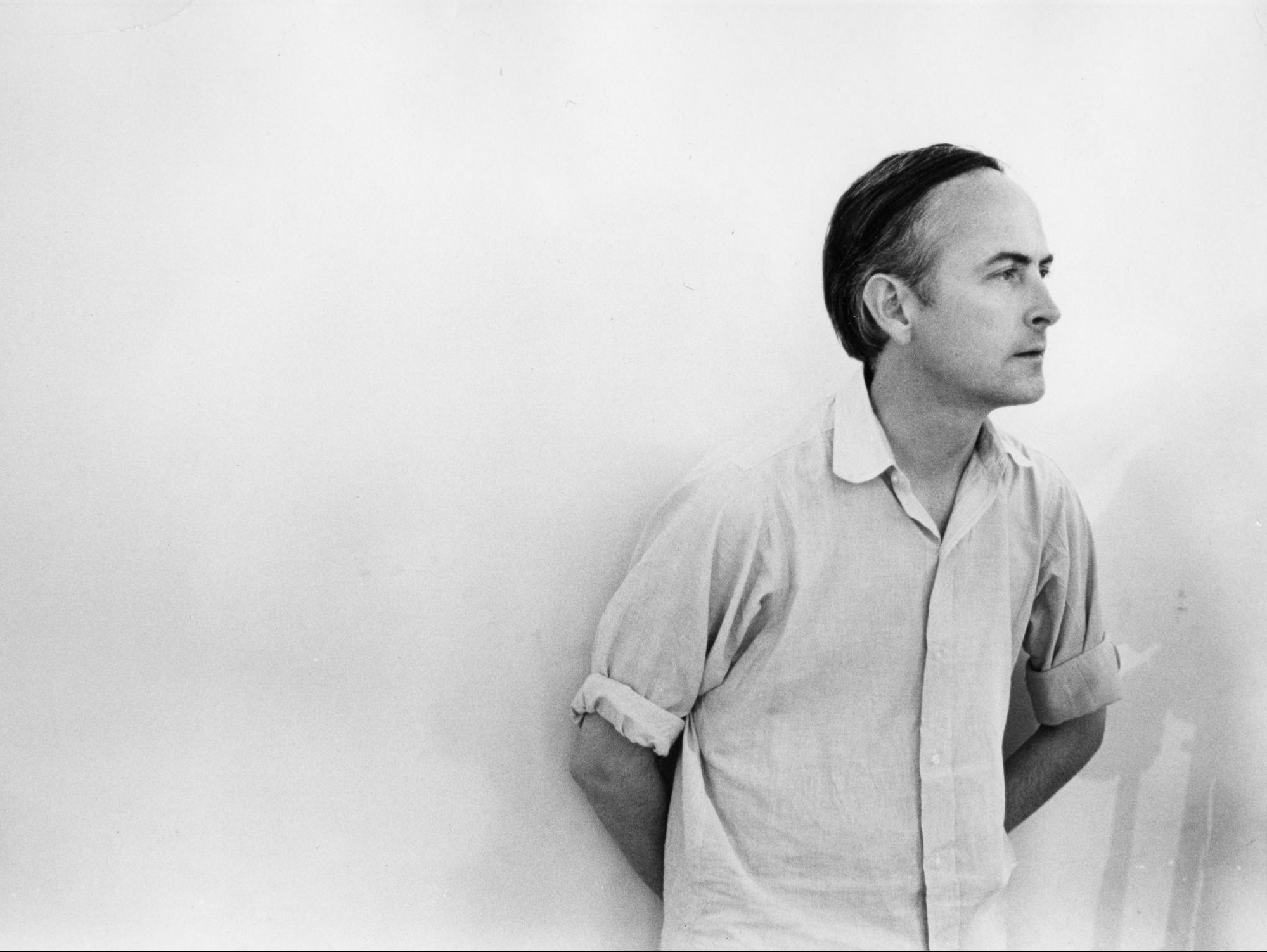

My love for the Foos was pure because I understood its fiction and preserved it that way. When my daughter gave me Dave Grohl’s memoir for Christmas I didn’t read it; I knew he was a real human being, with thoughts and feelings and relationships and a family, but I didn’t want to know the intimate details of his life. I’d never wanted to meet him, or get his autograph, or shake his hand, because the joy he gave me came from his music and nothing else. I also knew that to him I was just another purchased album, a mark-up on a piece of merchandise, a sold ticket, but that suited me fine. I was invisible, lost in a sea of heads in the audience, and within the safety of the crowd the music set me free.

Maybe the reason I fell so hard and fast for the Foos was because the relationship I saw on stage between Dave and Taylor was something I wanted, but couldn’t have. Even though I drank whisky and rode a motorbike and listened to rock music, everyone still thought I was a girl, so my friendships with men always ended with them wanting to have sex with me. But I didn’t want sex, I wanted what Dave and Taylor had; the mischievous, flirtatious, familial bond that they shared on stage. What they had together was stronger, richer and deeper than the beer-and-sex boorishness of Lad Culture that was prevailing in England at the time, and because I didn’t know how to create that kind of energy with a man myself, I wanted to experience it vicariously, to let it sink into my skin via osmosis along with the heat of the music and the smell of male sweat and the spittle that flew from Dave’s mouth.

He was hot, and dirty, and sweaty, and sexy—just how we liked him—and Taylor was his partner in crime.

And I felt it at every concert, which is why I kept going. As the band grew in stature, the venues grew in size, and eventually I became that fan who’d queue for hours so I could get into the stadium first and walk—okay, run, I have no shame—to the front of the stage. I wanted to be close because although Dave could fill stadiums with his godlike energy, it was the small gestures he reserved for those of us in the pit that killed me. He had us eating out of the palm of his hand. He’d stand at the front of the stage, covered in sweat, his hair all over his face, and yell out to the back of the auditorium, “How are you all doing back there?” and the roar of the crowd would rise up behind us. Then he’d look up at the nosebleeds, “And what about you up there?” and the roar would descend from above. Then he’d look down at us in the mosh pit and chuckle. “I know how you’re all doing,” he’d say with a smirk, and a few hundred fully-grown heterosexual men would suddenly find themselves entertaining fantasies of BDSM submission. He was hot, and dirty, and sweaty, and sexy—just how we liked him—and Taylor was his partner in crime, grinning his encouragement from behind his drum set. The two of them were a class act, and I couldn’t get enough.

Part of the joy of being at a Foo Fighters concert was how the band seemed to embrace us as equals, and we never felt it more than when Dave led us in the chorus of “My Hero,” the song that glorifies the ordinary, the one that brings tears to grown men’s eyes. Whether we were rock gods or garbage collectors—or trans dads living in the suburbs—the whole stadium would come together, our collective voices raising the roof off the rafters as we roared in full throated unison:

There goes my hero, watch him as he goes…

I still get goosebumps when I think about it. I guess that’s what being a die-hard fan feels like for me.

My kids are well aware of my obsession with the Foos; they know my ring-tone is a Foos song, they’ve sat patiently in the back of the car while I parked in a lay-by because the pre-sale for tickets coincided with the drive to school. I was having breakfast in a coffee shop in New York with one of my daughters when I heard the news. She was scrolling through her phone, because she’s a teenager, when suddenly she asked, “Hey, is Taylor Hawkins the Foo Fighters drummer?”

“Yes,” I replied. “Why?”

She looked up at me, her expression rapidly changing. “Oh,” she said. We were supposed to be having a fun day out together, and I could see in her face that whatever it was she was about to tell me would probably put the lid on that. She was right.

We were collectively grieving not just the loss of Taylor, but of the Foos as we’d known them.

It’s strange to feel the loss of someone you’ve never met so strongly. It seems inappropriate somehow, but the emotions don’t disappear just because you think they’re unjustified. Selfishly my first thought wasn’t about the band, or Taylor’s family, it was about my tickets for their next concert. The tour would be canceled, and unlike the gigs that had been postponed due the pandemic, it might not be rescheduled. The sense of belonging I felt in that crowd—the confidence that every couple of years I’d get to be part of it again—all that was now gone. How could the Foos be the Foos without Taylor? How could twenty five years of chemistry be replaced? It couldn’t, and as I walked around New York that morning with my daughter, I knew that across the world thousands of other fans were feeling the same way. We were collectively grieving not just the loss of Taylor, but of the Foos as we’d known them.

I ignored everything the press said about Taylor’s death, because it fell outside the auspices of my music-only boundaries. I knew who Taylor was to me, and that was all that mattered. Instead I waited for news from the band, and a couple of months later it arrived via social media. There was little information, just the dates of two tribute concerts; one in London and one in LA. I can’t go, was my first thought. They’ll play “My Hero” and I won’t be able to stand it. But then I realized that everyone else in the audience would be feeling the same way, which was why I needed to be there. It would be okay. We’d grieve together. Grown men would cry. It wouldn’t be the first time it had happened at a Foo Fighters concert.

So I started looking into the logistics; the LA concert was too close to my son’s birthday, but the London gig was feasible. Tickets went on sale at 9:00 am on June 17th, twenty four years and ten months to the day after I’d attended their first concert. Sure, England was a long way from where I now lived on the East Coast of America, but it was also the country where I’d first seen them, so it seemed fitting. I was all set with my credit card—website open, refresh button ready—when the lineup was announced. I read it while I waited for 9:00 am to arrive: John Paul Jones, Chrissie Hynde, Roger Taylor… my god, all my heroes were turning up. But then, at the bottom, a name I hadn’t expected: Dave Chappelle.

I froze. What was Dave Chappelle doing in a Foo Fighters lineup? I didn’t belong in an audience with Dave Chappelle; I knew this for certain because I’d felt compelled to watch The Closer after it led to the Netflix employee walkout. I’d gleaned from Trans Twitter that his jokes were offensive, but this alone didn’t seem to warrant the amount of attention he was getting; trans people are tougher than that, they usually only got this riled up when someone hit a nerve. Were people afraid he’d have some sway? Was he—god forbid—genuinely funny? There’d been only one way to find out, and that was to watch the show.

I needn’t have worried about him being funny—for the most part his humor was crude and obvious, transphobia in its most tedious form—but when he started portraying himself as a misunderstood ally, I understood why people had taken such offense. He claimed to have had a friendship with a trans woman, a fellow comedian, but this wasn’t friendship as I knew it; to earn his favor she’d first had to subject herself to his ridicule, to allow herself to become the butt of his jokes. He spoke of her with affection, and yet had treated her with contempt; she’d idolized him, and in return he’d humiliated her, continuing to use her for laughs even after she took her own life. Was this what he—and the world—demanded of us? That we should laugh along at our own humiliation or die trying? And if we could only prove ourselves worthy of affection by debasing ourselves, then what were our lives worth anyway?

9:00 am came and went and I didn’t hit ‘purchase tickets’. I couldn’t go to this concert. If Chappelle were on stage I’d feel the opposite of how I usually felt at a Foo Fighters concert: I wouldn’t feel loved and welcomed, I’d feel angry and excluded.

Surfacing out of my catatonic state I did a Google search. What had I missed by focussing only on the band’s music, and not on their lives? I discovered that the Foos had met Chappelle on the set of SNL, that he’d joined them onstage in Madison Square Garden the following June, a concert I hadn’t attended because someone in my family was immunocompromised and I couldn’t take the risk. Suddenly I felt like an idiot. My rigid insistence that I keep my devotion limited to the music and the music alone now seemed naive and stupid. If I hadn’t been so blinkered I’d have known about this friendship sooner; perhaps Dave had even written about it in his memoir.

I wondered if there would ever be an end to the losses I’d have to accept in return for my transition.

I wondered if there would ever be an end to the losses I’d have to accept in return for my transition. I’d known before I started transitioning that I’d lose some of my friends—although time, patience and open conversation had helped most of them to make the adjustment—but I hadn’t anticipated how much it would go on hurting every time I lost someone who lived beyond my reach. I couldn’t have an open conversation with an artist who didn’t know I existed, and it was only when I was forced to separate the artist from the art that I understood how hard it was to do.

The day of the London concert arrived. I saw the video the Foo Fighters posted online of the fans walking—no, running, they have no shame—to the front of the stage at Wembley Stadium, and then I logged off social media and busied myself doing something else. I didn’t want to think about it. I wanted to pretend it wasn’t happening. But the next morning a friend who hadn’t been privy to my inner turmoil texted me a link: Foo Fighters perform “My Hero” with Shane Hawkins.

Fuck, fuck, fuck, I thought. Shane Hawkins was Taylor’s son, and he was playing drums on the legendary song. Of course he was. I clicked on the link and watched him play, feeling my throat close up with emotion. Then I opened Instagram and looked at the photos the Foos had posted of the night before. The last shot in the series tipped me over the edge: it was a picture of the audience taken from above, a vast sea of lights in the dark. I should have been there, I should have been part of this, I should have experienced this feeling with them, among them, not sitting here alone at my desk, watching it on bloody YouTube. I swallowed my tears. It was too late to change my mind—I’d missed it, it had happened without me—and I had no idea who to blame.

Had I been too sensitive? Had I been excluded or had I excluded myself?

Had I been too sensitive? Had I been excluded or had I excluded myself? This was precisely why I’d never wanted to know anything about Dave Grohl in the first place; I didn’t want anything to interfere with my ability to enjoy his music. But I wouldn’t have been able to just brush Chappelle’s presence aside; he would have made me feel singled out—another sanctimonious trans activist who couldn’t take a joke—when all I’d ever wanted was to be part of the crowd. I hadn’t boycotted the concert because I was trying to make a point; I’d missed it because being there would have made me feel like shit, and the only reason I wanted to feel like shit at a Foo Fighters concert was because Taylor Hawkins was dead.

It’s too soon to know what the future holds, either for the Foo Fighters as a band, or for me as a fan. When people ask whether I’ve ever been a victim of transphobia I’m not sure how to answer; I’ve never been physically threatened, but sometimes the energy generated when someone attacks the trans community hits me after a delay, when I’m least expecting it. It reminds me that I’m different, and at times that can feel heavy. I’m still trying to tell myself that Grohl didn’t necessarily endorse Chappelle’s views. Maybe it was all irrelevant to him. Perhaps it had never occurred to him that he might have fans who were transgender, or if it had, he might not understand what Chappelle would represent to those people. Maybe he genuinely didn’t know how it would feel for us, seeing the man who made money out of mocking us up onstage with our beloved band. Maybe he’d never considered that including Chappelle meant othering a handful of his followers.

But the Foo Fighters are just men. They’ve never put themselves on a pedestal—never claimed to be perfect—so maybe I should cut them some slack. And if the hero of their song meant so much to us fans because he was human and fallible like we are, then maybe it shouldn’t hurt so much to admit that Dave Grohl might be human and fallible too.

There goes my hero, watch him as he goes;

There goes my hero, he’s ordinary…