A couple weeks back, in a write-up on “Mrs. Acland’s Ghosts,” your regular guide through greater Trevoraria noticed the emergence of certain micro-genres: Travel, Irish Gothic, “Person Losing Their Shit at a Party.” To these phyla I’d like to add School Stories, a category that contains this week’s entry, “Torridge,” alongside previously-discussed gems like “The Grass Widows” and “Mrs. Silly.”

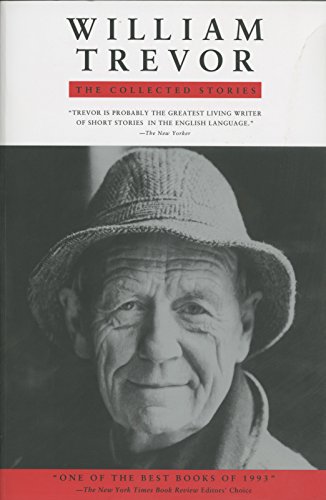

Like most of Trevor’s school stories, “Torridge” takes place at a boarding school. Trevor attended (or, per his 1991 memoir-in-sketches, Excursions in the Real World, endured) a handful of boarding schools as a child and later taught at one, and this authorial double exposure informs the story: unlike “Mrs. Silly,” where the narrative hews close to the adolescent protagonist’s POV, “Torridge” is a story about childhood—a particularly upsetting and cruel childhood—seen from the vantage of adults.

The first third of “Torridge” follows the titular character, the lonely son of a button-manufacturer and the frequent target of a trio of bullies named Wiltshire, Mace-Hamilton, and Arrowsmith. At their school there is a codified system of gay romances between older boys and their junior counterparts, called protectors and bijoux, respectively, to which Wiltshire, et al. already belong. Torridge receives a note from an older boy named Fisher, asking him to be his bijou, only to learn later that this note was meant for Arrowsmith. In the wake of this mix-up, Fisher tries again to connect with Arrowsmith, but is roundly mocked and leaves the school suddenly, prompting an assembly where the headmaster vaguely denounces the protector-bijoux arrangement. This does little besides confuse the students, and the system remains firmly in place, with Arrowsmith, Mace-Hamilton, and Wiltshire eventually taking on bijoux of their own. Torridge, notably, never partakes, remaining aloof and alone throughout his remaining years there. The note mistakenly left for him passes into school legend.

After a section break, we move decades into the future, to a dinner reunion of our three bullies. Wiltshire, Mace-Hamilton, and Arrowsmith are all married now, two of them with families. Roughly once a year, they all reconvene for dinner, where the talk turns inevitably to Torridge, who, as he did at school, has become something of a comic legend—a figure of fun even for children he’s never met. Arrowsmith, unbeknownst to the others, has invited Torridge to this dinner. Torridge arrives and soon tells the assembled that he himself is gay, and then goes into detail about protectors and their bijoux, explaining frankly that the fathers and husbands at the table were enthusiastic participants in this system. In a final, brutal reveal, he tells them all that Fisher, the boy who mistakenly courted him, did not return to school because he had hung himself, leaving a note for Arrowsmith at his feet.

What is initially striking about this story is, of course, the protector-bijoux system. That boys would groom even younger boys is disturbing, though Trevor seems to reserve judgment about the relationships themselves, focusing instead on the opportunities for cruelty that those relationships create. For example, Arrowsmith, pursued by Fisher after the initial mix-up with Torridge, reads the older boy’s pleading letters aloud for fun, a detail that gathers heartbreaking weight once Torridge reveals Fisher’s suicide. It’s easy to think of the lonely older woman as Trevor’s go-to archetype, but he is just as proficient writing the breathtakingly vicious adolescent. (See also: “Broken Homes,” and “Bravado,” which appeared in the New Yorker).

As a story about queerness, “Torridge” certainly has its flaws, especially when viewed through a contemporary lens. Torridge feels a bit stock as a fastidious gay man with a “step as nimble as a tap-dancer’s.” Furthermore, I found his revelation of both his sexuality and Fisher’s grim fate a bit salacious, though I’d argue that’s more to do with structure and mechanics than content. “Torridge” is an oddly shaped story. In the first third, we proceed by Trevor’s steady expositional churn, doling out a bit of POV here, but mostly zeroing in on Torridge, though never entering his perspective. The first sentence of the story is indicative of that narrative distance:

Perhaps nobody ever did wonder what Torridge would be like as a man—or what Wiltshire or Mace-Hamilton or Arrowsmith would be like, come to that.

There is an effortlessness to this opening section, which appears even smoother when contrasted against the blitz of the dinner party, in which Trevor enters the interiority of 10 characters, by my count: Torridge’s three middle-aged tormentors, each of their wives, three of their children, and even, very briefly, the waitress serving them. This cascade of multiple points of view is consistent with other stories written during the same period, like “Teresa’s Wedding.” But where that story uses a bushel of POVs to sketch a portrait of small-town despair, the roving narrative camera in “Torridge” exists mostly to capture the reactions to the bomb Torridge has set off. This is where that icky feeling of salaciousness comes in. While it is satisfying to see a complete shitheel like Arrowsmith exposed (something that rarely happens in Trevor’s fiction; usually the victims bear their lot in dignified silence), this exposure relies too heavily, in this reader’s opinion, on the spectacle of his dubious, and Torridge’s stated, sexuality.

“Spectacle” is not a word one often associates with Trevor, but that’s what makes this story so interesting. “Torridge,” especially in its final section, feels like the ungainly hybrid of a story and a play, down to its theatrical premise: a stranger with a secret comes to dinner. Trevor wrote several plays, for stage and for radio, and while I do not question his dramaturgical chops, I found myself drawn more to the deft, empathic summary of the first section, which feels more consistent with the very best of his stories.

And the story is still a technical masterwork. Take a look again at that first sentence and notice how it both begs the question the story will answer and slyly disguises it through its conversational construction. The broad uncertainty of that first sentence also quietly prepares us for the whirligig POV in the final section, following the writing class axiom that a story should start wide before it narrows. Note, too, how Trevor strategically withholds Torridge’s point of view, only letting us see him from a distance—at first a figure of fun and later the only person to emerge with their dignity intact.

Up next, “Death in Jerusalem.”