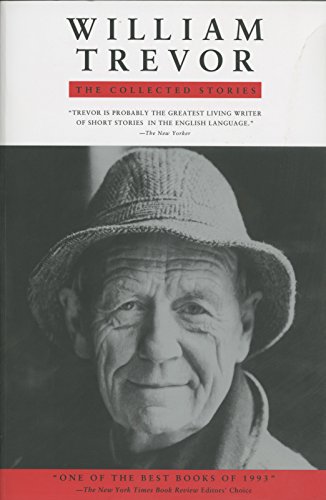

“The Wedding in the Garden” is another elegant one that follows more or less the usual formula. Christopher Congreve is the scion of an upper-class hotelier family. Dervla is the dining-room maid. Through their early adolescences, marked by Christopher’s coming and going to boarding school, they grow enamored of each other, eventually professing their love and carrying on a romance in Room 14. Mr. and Mrs. Congreve somehow discover the tryst and predictably object, threatening Dervla with unemployment and Christopher with the loss of his birthright—the grand hotel that he will soon inherit and occupy—and insisting she write a letter that severs things. She does, and Christopher moves past it, in time falling in love with an Archdeacon’s daughter. But Dervla does not move past it—will never move past it—and we leave the two principles at Christopher’s hotel wedding reception, with Dervla haunting Christopher as we are given to know she will for the rest of Christopher’s and his oblivious new bride’s lives.

For the story to have power, the reader must believe that this state of things will persist, and for the state of things to persist, the characters must evince no capacity for action or change over the course of an entire lifetime. This fundamental incapacity to act is an element many if not most Trevor stories are premised on. If a reader were to believe a person in Trevor-world could make, in modern parlance, proactive change, how many of the stories in The Collected would fall apart like a Jenga tower with a foundational piece jerked away. We believe these people cannot change because we are told they can’t, and as well, because of a more implicit atmosphere of paralytic stasis that creeps like a sinster fog through these stretches of Irish countryside, and London streets, and grand hotels such as the Congreves’.

We also believe it, I think, because of the place and era when these stories were written. Though many of these pieces were written and set in the ’80s and ’90s—with later ones in the Selected reaching into the new millennium—they are of a mid-century, post-war era of silently fraught teatimes, of keeping calm and carrying on. The worldview in these stories is firmly pre-therapeutic, as pre-therapeutic as Dickens or Austen. People are what they are. They have, at best, one moment of revolt in them against their natural selves and the natural order—an order constituted by fate’s dealing of natural selves, of birthright, class, identity, temperament, and personality—and then they fall back in line, as Dervla and Christopher both do, in their respective ways. There is no serious time or thought paid to the prospect of breaking out, breaking away; it is unthinkable, in the most basic sense. This is, of course, a stereotypically British thing as much as it is a mid-century thing. While Roth and Bellow and the great American mid-century writers were exploring new sexual and behavioral horizons (for men, anyway), Brits continued stiff upper lipping it through at least Remains of the Day, and a vestige of this anti-therapeutic regime can still be seen in the droll stoicism of very modern writers like Rachel Cusk.

We also believe it, I think, because of the place and era when these stories were written. Though many of these pieces were written and set in the ’80s and ’90s—with later ones in the Selected reaching into the new millennium—they are of a mid-century, post-war era of silently fraught teatimes, of keeping calm and carrying on. The worldview in these stories is firmly pre-therapeutic, as pre-therapeutic as Dickens or Austen. People are what they are. They have, at best, one moment of revolt in them against their natural selves and the natural order—an order constituted by fate’s dealing of natural selves, of birthright, class, identity, temperament, and personality—and then they fall back in line, as Dervla and Christopher both do, in their respective ways. There is no serious time or thought paid to the prospect of breaking out, breaking away; it is unthinkable, in the most basic sense. This is, of course, a stereotypically British thing as much as it is a mid-century thing. While Roth and Bellow and the great American mid-century writers were exploring new sexual and behavioral horizons (for men, anyway), Brits continued stiff upper lipping it through at least Remains of the Day, and a vestige of this anti-therapeutic regime can still be seen in the droll stoicism of very modern writers like Rachel Cusk.

If we believe that modern citizens of the world have more agency and more available choices of who and how to be—a dubious claim, but for the sake of argument, let’s say it’s true—then one of the results of having more choices must be a felt sense that our choices matter less. Every wound can be healed, every course corrected, every mistake forgiven. If this is so, it is an improvement for society but arguably literature’s loss. It is difficult to imagine a modern fiction that could believe this strongly in the adamantine power of one embrace in a hotel room, one stern word from the head of a household—that these single moments might shape an entire lifetime, several lifetimes. A modern version of “The Wedding in the Garden” is difficult to imagine simply because none of the narrative action would or could have so much consequence. Dervla would find other work, or Christopher would politely ask her to leave, or he would otherwise explain their long-ago assignation to his new wife in a lengthy couples therapy session. The dreariness I feel typing that out goes a long way toward explaining the difference between what matters in fiction and in real life.