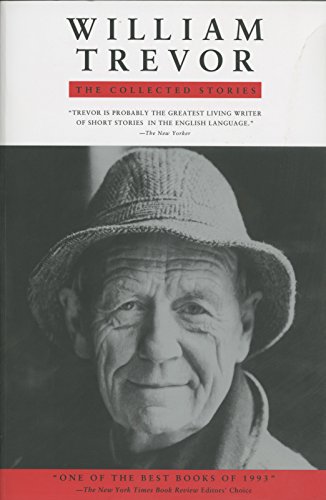

“The News From Ireland” is the second novella in The Collected after “Matilda’s England,” a stout 25-pager that feels to me just a bit longer than a short story. Or that is to say, it seems to do more things than a short story does or can. Not all of them successfully— “Matilda’s England” I consider to be a small, complete masterpiece; “The News From Ireland” feels more like the prospectus for an actual novel, with a large array of characters whose individual stories are started and left in the narrative lurch.

The main story concerns a butler named Fogarty, who runs a house in the Irish countryside during the Great Famine. The house’s old owner, Hugh Pulvertaft (another great Trevorian English name for the books) has died, and the house has been moved into by the English part of the family, the Ipswich Pulvertafts, as Fogarty refers to them. The Ipswich Pulvertafts have brought a governess with them, Anna Maria Heddoe, as well as a one-armed estate manager, Erskine. Fogarty devises a plan to frighten Miss Heddoe away via a story of local people giving their baby a false stigmata—he hopes the story will cause her to leave, and that it might also stir up anti-English sentiments that could cause Mr. Erskine to be attacked by the local workers, and that these events could cause the Pulvertafts to see the error of their ways and return to Ipswich (if this sounds incoherent in summation, it felt likewise in the unabridged form). The story, or novella, takes as its form an alternation between Miss Heddoe’s diary entries and a roving Trevorian third person, albeit in the unwieldy present tense.

The entire story feels unwieldy, both overambitious and unfocused. Mr. Fogarty, in particular, is indistinct. It’s clear that he feels the Pulvertafts and Erskine and Miss Heddoe are invaders who do not belong in Ireland. But given the duration of time they have already been there, as well as his vested interest in the house remaining a plausible place of employment, the motivation feels strange and somewhat insufficient to me. We are told early on that “in Fogarty’s opinion it is a pity the process [of abandonment and decay] didn’t continue until everything was driven back into the clay it came from.” And that if it had “he and his sister [the house cook] might alone have attended the mouldering of the place, urging it back to the clay.” It is never clear, however, why he wants this to occur. As is arguably too often the case with Trevor’s protagonists, they are motivated by a desire that does not feel especially believable or even human in its obsessiveness and, to a degree, its arbitrariness. Fogarty’s desire is not so much the desire of this particular butler, as it is the desire of a kind of Irish consciousness.

An intriguing thing about “The News From Ireland” is that it is historical, one of a handful of Trevor’s stories set firmly in the actual past. I say actual past because so many of his stories, maybe most of them, feel like the past but are not. The majority of the stories in The Collected were written after the mid-seventies, some into the nineties, yet almost all of them feel emotionally located in some hazy post-war fifties moment. I have long held the theory that everyone, in a way, writes historical fiction—most people are not writing about the moment they’re writing in, but some indefinable moment in the past at which the world felt most understandable to them. For most people, I would venture to say, this moment is during their adolescence. No matter how many scenes I write in which characters are texting or taking Ubers or worrying about Covid-19, the default moment of my stories is around 1990 or so—I often find anachronisms like FM rock radio sneaking in as background if I’m not being attentive.

More so than technological or cultural details, I think the emotional mode of the time period when a writer came of age tends to persist, often in almost inarticulable ways. No matter when I set a story, it is emotionally located at the moment when I—along with seemingly the entire world, judging by the groundbreaking reputation of Seinfeld and various self-aware ad campaigns—suddenly understood and began using irony. Likewise with Trevor, despite the appearance of color TVs and the disappearance of wirelesses in the second half of The Collected, almost all of them feel emotionally located in some hazy post-war moment from 1948-1952. Not just the sexual repression—although yes that—but a stateliness of formal thought that seems intrinsically located in a past that was not televised (to say nothing of internetted).