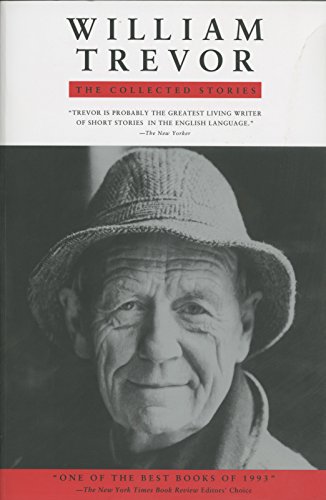

I’ve mentioned before that one of the pleasures of a project like this is the way certain types of story begin to recur and constitute subgenres of the author’s output, categories of which the author may or may not have even been aware. As we approach the midway point of the Collected, several Trevorian modes begin to repeat, some rather insistently. For instance, and very generally, there are a large clutch of stories inspired by travel that take place on the continent. There have also been more than a handful of “Person Losing Their Shit at a Party” stories, about which I’ve written fairly extensively.

“Mrs. Acland’s Ghosts” represents another strain of Trevor story, namely a kind of Irish Gothic, also represented by the likes of “Miss Smith,” “The Hotel of the Idle Moon,” and “In at the Birth.” These stories, and a few others like them in the collection, more surely soon to come, have much in common with their compatriots in the Collected, but with aspects that nod toward the tradition of gothic horror. In the case of “Mrs. Acland’s Ghosts” the gothic element is to be found in the mode of storytelling itself. The bulk of the story is a letter written by a Mrs. Acland, a woman institutionalized by her husband for seeing ghosts, to a Mr. Mockler, a 63-year-old tailor who has apparently been chosen randomly as a recipient. The framed epistolary form is, of course, familiar from novels like Dracula, Frankenstein, and, particularly, The Turn of the Screw, which frames the governess’s eerie tale several layers deep. There is something inherently unsettling about this form of narrative—I don’t just mean a character receiving a strange letter, which, of course, nests one person’s story into someone else’s. There is a way that the story at hand, and its significance, feels somehow attenuated by the reader-character/narrator’s presence just outside the frame. The story makes this diminishment explicit at the end, seeing as Mr. Mockler muses about the sadness of Mrs. Acland’s ghosts—her imagination, in other words—not being honored.

It occurs to me, writing this, that even in the non-gothic/horror stories, there is often a related atmosphere to be found in the Collected. Needless to say, few stories in the Trevor canon (and, really, few in the canon of great short stories) are cheerful or sunny. The general weather and mood of these piece is one of oppression: darkness, clouds, rain, damp; the average Trevor protagonist or narrator is likewise oppressed by the immutable facts of their life. There is also, as noted previously, a taste for the macabre or grotesque character that evokes O’Connor and early Ian McEwan. Beyond these specific genre markers, however, I think there’s a specific quality of irrevocability in the gothic that speaks to Trevor’s worldview.

“Mrs. Acland’s Ghosts” offers an extreme example of this aspect. As the sinisterly named Dr. Friendman informs Mr. Mockler “All her childhood, Mr. Mockler, her parents did not speak to one another… In the house there was nothing, Mr. Mockler, for all her childhood years: nothing except silence.” That summary description of the isolation and silence Mrs. Acland endured in her childhood is not a human span—it is a span of Stokerian, Poeian terror. And the terror exists not only in the duration of that traumatizing silence, during which she dreamed up the ghosts that keep her company, but in the almost mythic quality of its absoluteness. Trevor’s characters so often, in some fundamental way, are born into and live most comfortably in darkness. The pure depth of isolation and misery depicted in many of these stories feels similar to the fairy tale and myth from which the gothic derives much of its energy.