The Toughest Fish in the Barrel

The Old World

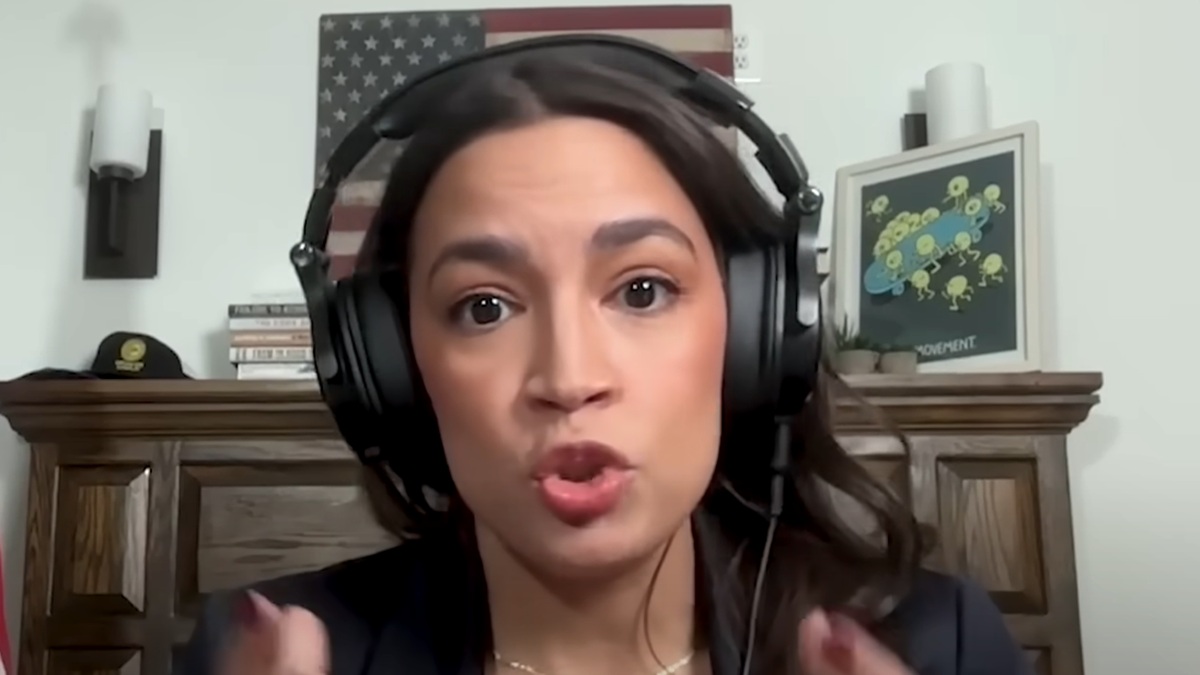

Sunrise Foods, just a few blocks from my house, is marked by a glossy freestanding sign, a cheery egg-yolk yellow against an often gray, wintering Toronto sky. Back in December, just before I turned 14, Tracey “with an e” recruited a bunch of us from the school lunch table to work here in her uncle’s new bagel and smoked fish store. Now, six months on, all my peers are gone. But I have learned to tell whitefish chubs with their oily, golden hue from goldeye that wrinkles away from the skin. I’ve learned how to sheath my arm in a plastic bag and plunge it into a barrel of gutted herring, floating in their vegetable oil pond. How to act like I wasn’t afraid to touch the fish until I wasn’t afraid to touch the fish.

At the barrel I re-tie my white apron over the green Roots Athletics T-shirt I bought with my first paycheck, protecting it from oil splashes that never wash out. My dirty-blonde waves are pinned on top of my head with a clip of faux pearls. A berry-scented hair spray from a purple bottle helps disguise the fish smell.

I’d had an argument with my mother just before I was hired at Sunrise. She was annoyed that the sleeves of my winter coat no longer reached my wrists, that I was yanking my shirt sleeves down to my mittens to cover the gap. My growing body and its expense had slipped her mind. I had to agree to chip in my birthday money, but I got to choose the store and the new coat. Then it hit me: birthday cards only come once a year. I really needed a job.

The customer’s eyes follow my arm as it disappears into the dark oil. I reach around blindly. Even in a barrel, the fish resist being caught.

I’ve seen my mother eat herring from a little glass jar, lifting scraps of the silvery sliced fish onto a Triscuit with her fork or sometimes her fingers, and sliding the cracker onto her tongue like it’s a delicacy. Her family served it at all kinds of holidays when she was growing up.

At the Sunrise counter, though, you can buy herring sliced in oil, in cream sauce, or in wine vinegar with red onion and black peppercorns. But barrel herring is high-drama herring. “Time for herring theater,” I whisper to Hymie, who speaks Yiddish with the uniformly geriatric customers, and makes our best-selling tuna salad with a secret ingredient (chicken bouillon powder).

The old folks are picky about the exact herring they want—or pretend to be, so they can watch me do it again. This gives them something to get excited about in their day. “Once I’ve put it back, I can’t get it again,” I say to a little old lady, plastic shopping bags dangling from her wrists.

Held dripping over the barrel, the herring looks back at me with its black eyes, immobile tail, and a seam on its belly where the insides were cleaned out. “This is a really healthy one,” I say to the little old lady. I’ve learned this is what every customer wants to hear.

When she leans in to approve her herring, I instruct myself not to stare at her thin forearms peeking out from her sleeves. The chain of blurred numbers inked into them. The miracle of survival. Of anyone’s, of mine. Then, like a magician, I briskly turn the bag inside out over my hand and let the fish flop into the bottom of the clear bag. The little old lady looks up at me from behind enormous macular-degeneration sunglasses and gasps, then claps.