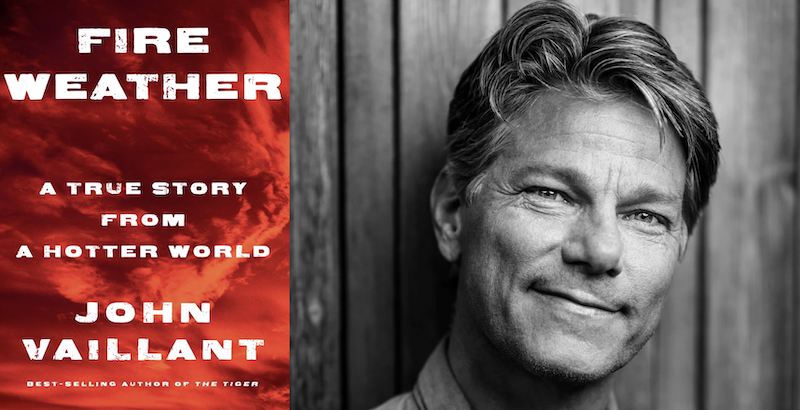

It’s the morning after the night before, but John Vaillant is not running on empty. Instead, the 62-year-old, Vancouver-based writer, whose book Fire Weather has just won the £50,000 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction, appears ready for action as he gives interviews from a London hotel room. Our conversation takes place over Zoom, and ends only when one of the prize’s administrators reminds him that he needs to eat some lunch.

But Vaillant, it quickly becomes obvious, is energized not merely by literary victory, but by a profound sense of mission: Fire Weather, he hopes, is a book “that speaks to where we are now, in terms of energy, in terms of lifestyle, in terms of climate, in terms of the new combustibility of our world”.

Also obvious is his gift for alighting upon stories that are utterly gripping on their own terms and that also illuminate wider issues of how human beings interact with their environment; and of the urgent necessity to radically renegotiate the terms of our habitation of the planet. Fire Weather, which took Vaillant seven years to write, focuses on the forest fire that hit the petroleum colony of Fort McMurray in 2016, in which 90,000 residents were forced to evacuate during the course of a single day, and during the course of which thousands of buildings were all but vaporized and 2,300 square miles of boreal forest were burned.

Intensified by unusually high temperatures, unusually low humidity and the forest’s extraordinary combustibility, what Vaillant describes as “a regional apocalypse” took over a year to fully extinguish: on the afternoon of the evacuation “cell phones and dashcams captured citizens cursing, praying and weeping as they tried to escape a suddenly annihilating world where fists of heat pounded on the windows, the sky rained fire, and the air came alive in roaring flame. Choices that day were stark and few: there was Now, and there was Never.”

The scenes that Vaillant describes in Fire Weather seem to the reader to belong to the world of blockbuster disaster movies and CGI effects; incomprehensible in scale, ungraspable in their sudden shifts, dominated by the lurid, hallucinatory colors of the most melodramatic nightmares. But woven through this hellscape is a parade of quotidian human moments that allow us to understand how it might have been: the residents who still thought they might have time to pick up their dry cleaning, the city official who, in an under-reaction to rival the mayor in Jaws, simply advised the community not to set off fireworks or put out their recycling as the fire approached.

The scenes that Vaillant describes in Fire Weather seem to the reader to belong to the world of blockbuster disaster movies and CGI effects; incomprehensible in scale, ungraspable in their sudden shifts, dominated by the lurid, hallucinatory colors of the most melodramatic nightmares.

The numerous interviews that Vaillant conducted in the aftermath of the fire impressed on him the profound shock that the Fort McMurray fire caused. On one level, it was easy to understand in the context of a town that exists entirely to serve a petroleum industry that runs 24/7, 365 days a year: “These plants are so huge that if you shut them down, you could actually break them because they never shut down. You’re talking about millions of dollars a minute for a shutdown. And in 2016, that was only two years after a really radical downturn in global oil prices. So the last thing anybody running or owning a petroleum facility is going to want to hear about is a shutdown.”

Just as significant is a very human desire, he believes, that “transcends partisanship, or climate denial, or intelligence”, a long-practiced impulse to “want to do the thing that we planned to do that day. And if a fire comes into town to stop us, we’ll eventually respond to it. But there’s going to be some gear-grinding in there as our heads readjust and recalibrate to this new reality.” And this is where the challenge arises for individuals struggling to know how to respond to the imperatives of the present emergency, and where Vaillant hopes his work can help to provide a vital bridge.

“Climate change is changing our reality right now,” he insists. “And we are resistant to acknowledge it. We want to stay in the world that we know that’s comfortable, where we know what the rules are. But the rules are changing now. One of the goals of the book is to say, this is what it looks like when ordinary people have the rules of their lives forcibly changed right under their feet.

And it’s going to be easier if we anticipate this and prepare for this rather than being in this reactive situation that everybody in Fort McMurray was, in part because the leadership didn’t interpret the very clear signs in a meaningful way, and that created this traumatic exodus. There could have been an earlier evacuation, that would have created its own set of problems. And there’s no easy way to deal with it. But there was also no way to put the fire out. It was an unstoppable fire, because that’s how combustible the forest is now.”

One of the goals of the book is to say, this is what it looks like when ordinary people have the rules of their lives forcibly changed right under their feet.

Vaillant’s first book, The Golden Spruce, revolved around a man called Grant Hadwin, a former logger and a forestry expert who, in 1997, swam across the freezing waters of the Yakoun River in British Columbia towing a chainsaw. Once on land in the Haida Gwaii archipelago, he inflicted a number of “felling cuts” on the only giant golden spruce in the world, causing it to collapse a couple of weeks later, as soon as there were high winds; the grief and outrage united all sections of the community, including the Haida people, to whom Kiidk’yaas was sacred. (This will have particular resonance for those in the UK, still reeling from the deliberate felling of the Sycamore Gap tree, near Hadrian’s Wall, in September.)

Not long afterwards, Hadwin—a highly singular man given to drinking vast quantities of vodka, wearing spurs on his trainers and subject to episodes of paranoia—disappeared, leaving behind him only the kayak in which he had planned to paddle to court. He had also sent letters to the press, Greenpeace and the Haida community declaring his reluctant attack on the tree to be “a message and a wake-up call” to the logging companies—an expression, he said, of “rage and hatred, towards university trained professionals and their extremist supporters, whose ideas, ethics, denials, part truths, attitudes, etc., appear to be responsible, for most of the abominations, towards amateur life on this planet.”

It’s evident that Vaillant, too, believes fervently in the need for a global wake-up call, although it is scarcely imaginable that his methods would be so destructive—of the natural world or himself. “If I was a Doomer,” he tells me, “I could not have written this book. Why bother? You know, I have kids, I’ve got a lot of years left, assuming all things go reasonably well. And I’m here for it. This world is really beautiful—it’s an amazing thing that we get to participate in and experience.” But the continuation of the status quo is not an option and, Vaillant explains, our new reality demands that we decarbonize as rapidly as possible and, in the process, embrace an energy transition.

Writing Fire Weather enhanced Vaillant’s appreciation of our kinship to combustion and to the multiple ways in which it has literally empowered and enlightened us. “You don’t have to be a petroleum executive or a stockholder to be enriched by petroleum,” he notes. “We’re enriched by petroleum just by being able to move through space so quickly in a car, and we’re able to stay connected to more friends, family members and job opportunities, because of this enhanced power that we have.”

But there are also numerous and burgeoning opportunities for its replacement—he points to the vast renewable energy projects being rolled out in places as politically diverse as China and Texas, even as their fossil fuel industries continue. He also thinks that lawsuits such as that brought recently by the state of California against oil and gas companies including Shell and BP for failing to reveal the dangers of fossil fuels will “move the needle”, as will the increasing ability for businesses to obtain fire insurance.

He is not, however, naive enough not to appreciate the lengths that some will go to in order to protect their vested interests. In October, he appeared as a witness at a special session of the Canadian parliament’s natural resources committee. Despite the already tight security, the CEO of Suncor, Richard Kruger, arrived with additional bodyguards, and adopted a similarly stonewall approach when he was questioned about corporate responsibility for mitigating the climate crisis. “You already kind of get the idea where this guy is, and you’re not going to get a straight answer from him,” recalls Vaillant. “He will not tell the truth about it. And watching this MP grill him, you know, with a stack of evidence in front of him and watching this guy bobbing and weaving…” he trails off, clearly frustrated.

That is why, he explains, he stuck largely to interviewing residents and firefighters in Fort McMurray. “I feel like where the real information is, where the real value is, is on the ground in nature, with people who are undefended, who don’t have bodyguards, who are having to face it alone. And I have real compassion for them, and deep concern for them. They’re really seeing it in this unvarnished, uninsulated way. And that’s what we need to see, as readers. I don’t want to give you the polished version. I want to give you, I was taking a shower, having a perfectly decent morning, I stepped out of the shower, and there’s a black sky where there had been a blue sky.”

As well as The Golden Spruce, Vaillant is the author of The Tiger, another deeply researched, ground view account, this time of a community on the far eastern border of Russia suddenly terrorized by a Siberian tiger, from a subspecies not generally known to attack humans but destabilized by a combination of poaching, habitat destruction and the illegal wildlife trade. It was followed by a novel centering on an undocumented Mexican immigrant, The Jaguar’s Children; Vaillant was working on his second novel when the Fort McMurray fire hit. He also reported from the Carr fire in Redding, California, in 2018. What might be next for him?

He is aware of the tension between writing and activism and, he says, there were moments during work on the book when he wondered, “Why are you sitting in your office doing this 20th-century bourgeois thing when you should really be out blocking a pipeline or stopping traffic?” He has taken part in various actions—“Haven’t been arrested yet”—but also sees the value of being part of a dialogue, including with organizations such as Baillie Gifford, who have been sharply criticized by the literary world for their investments in fossil fuel companies. “I’m really trying to find a way to have a conversation where one side isn’t shaming or rejecting and the other side isn’t lying and greenwashing. Trying to cut through some of those sort of standard defense tactics. How do we crack this nut in a meaningful way, in an honest way?”

It is, he says, “an amazing moment to be alive. It’s scary on the one hand, but it’s also super exciting. And the bottom line is, you’ve always had to be brave to be a human being. Whoever your ancestors are, think about what they came through. And one thing they came through and one reason they persisted, as they did to the point that we now exist, is that they did not do that to see us give up. Think of all the endings they had to endure. Think of all the futility they had to experience wherever they came from, in whatever circumstance that might have been. And for some reason, they pushed through. And we’re descended from them. That’s our stock. That’s what we come from. So I think we can do this.”